Posted by: Ken @ 10:47 am

Good News FLASH! — May 30, 2008

It’s official–

Broward County Now Has Its First Active Bald Eagle Nest of the 21st Century!

I just spoke with Janell Brush, Biologist with Florida Fish and Game Conservation Commission, and was amazed to learn that the nest was discovered in an aerial survey on April 9, 2008, and found to contain one fledgling. Given FWC ID#BO-002, located in Pembroke Pines, 1/4 mile west of US-27 at coordinates N 26.00.44, W 80.25.59 (or N 26.00733, W 80.42650 degrees). It will not appear on the Eagle Locator Map until FWC revises it around mid-June.

Kudos to the pilot (whose name I do not know), who has 30 years of experience finding and monitoring eagle nests…

I am amazed that he saw the nest, as it was flush against the trunk of a live Australian Pine. As you can see from my photo below, it is barely visible from the ground. Apparently, he found the nest cold– no one had reported it at the time!

The last known eagle nest in Broward County was found in 1997, an inactive one in the Miccosukee Reservation, far to the west, near the Collier County line.

Ken

Eagles courting, on the roof of a neighbor’s house, December 4, 2007:

Eagles copulating, December 4, 2007:

Early this past December, I photographed two Bald Eagles courting and copulating at our (South Florida) lake. Within the next 2 weeks they were seen carrying nesting materials to a wooded area near a busy intersection not far away. Despite searching the area, we were not able to find the nest until a neighbor finally located it on April 20. The observer stated: “I didn’t want to linger around and draw attention to the nest but I did notice an eagle flying overhead. It was flying high and it appeared mottled like a juvenile. I really hope this property is not slated for development but I suppose it is only a matter of time.”

This morning I got out and photographed the nest. It is obviously fresh and quite large, about 4 feet in diameter. It is only about 2 miles from our home, and located about two-thirds of the way up in an Australian Pine tree. This is in the same direction as that followed by the eagles that visited our lake, as well as others seen bringing branches and fish from other nearby lakes.

Therefore, it is very likely the nest of “our” pair. The nest site is within sight of a major thoroughfare, about 100 yards from the edge of a 1/8 x 1/4 mile rectangle of drained and formerly cultivated or grazed Everglades, now covered by a relatively undisturbed second-growth forest of Melaleuca & Australian Pine. The first recent record of an eagle nest in Broward County, it is on private land, surrounded on two sides by residential subdivisions, with ever-expanding retail and other commercial development nearby.

Eagle Nest, May 29, 2008:

Updated photo, taken on October 17, 2008, shows the nest to still be in good shape:

The Bald Eagle was removed from protection under the Endangered Species Act in 2007, and was recently taken off Florida’s endangered species list. Last month, a spokesman for the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission stated: “The eagles are recovering in Florida with 1,100 active nests counted last year after a low of 88 nests counted in 1973. Monitoring and development restrictions remain in place even after the delisting.”

This is reassuring, but how vigorously will their nest sites be monitored? Eagles tend to re-use prior nesting sites. Given the reduced protection now afforded the species, what can be done to prevent disturbance of this nest? We will keep the location secret, but have notified the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission with our concerns. Please do not contact us for this information. Once this nest is entered into the Florida FWCC Nest Locator, you may find it at this Web site:

Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission Eagle Nest Locator

In order to obtain a better understanding of how protection of the Bald Eagle has been changed, we consulted the FFWCC Bald Eagle Management Plan (PDF Document, Published April, 2008). It truly is interesting reading. Seventy-four pages long, the Plan contains a wealth of information about the breeding biology of Florida’s eagles. It includes a map of all known active eagle nests in Florida, as of 2005-2006. None were recorded as nesting in Broward County. The Plan notes that native pines are favored nesting sites, usually within 1.8 miles of a body of water.

“Most clutches of eggs in Florida are laid between December and early January… with most nests containing two eggs. Incubation lasts about 35 days… Nestlings in Florida fledge at around 11 weeks of age and remain with their parents near the nest for an additional 4 to 11 weeks… Fledglings begin widespread local movements before initial dispersal, which occurs from April to July…”

Eagles have special federal protection in addition to that afforded by the Endangered Species Act:

“…During 2006, the USFWS proposed removing the bald eagle from the list of federally endangered and threatened species, and this action was finalized in August 2007. Although the bald eagle is no longer protected under the Endangered Species Act, it is still protected under theBald and Golden Eagle Protection Act and the Migratory Bird Treaty Act. The USFWS (2007b) has redefined some of the terminology included in the Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act, which prohibits the unpermitted “take” of bald eagles, including their nests or eggs. The act defines “take” to mean to “pursue, shoot, shoot at, poison, wound, kill, capture, trap, collect, molest or disturb” an eagle. The new definition of “disturb” is to “agitate or bother a bald or golden eagle to the degree that causes, or is likely to cause, based on the best scientific information available, 1) injury to an eagle, 2) a decrease in its productivity, by substantially interfering with normal breeding, feeding, or sheltering behavior, or 3) nest abandonment, by substantially interfering with normal breeding, feeding, or sheltering behavior” (USFWS 2007b). This management plan adopts the federal definition of “disturb” in 50 C.F.R. § 22.3 and Florida’s definition of “take” in Rule 68A-1.004, F.A.C.”

Federal law and regulations protect the nesting habitat of Bald Eagles, irrespective of their status under the Endangered Species Act:

“The USFWS (2007b) Bald Eagle Management Guidelines help the public comply with the Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act by avoiding activities that disturb bald eagles. These federal guidelines serve as the basis for the FWC Habitat Management Guidelines recommended in this management plan to ensure compliance with Florida wildlife laws concerning bald eagles (see Permitting Framework), and to minimize potentially harmful activities conducted within 660 feet of active or alternate bald eagle nests. In addition, the FWC recommends that nesting habitat be managed as described in the preceding section on habitat management.”

Under the Florida FWCC Plan, there are incentives for private landowners to protect the eagles:

“Private lands play an important role in the long-term conservation of bald eagles in Florida, currently supporting about 67% of all currently known nests. To promote the enhancement of bald eagles and eagle habitats on private lands in Florida, the FWC will:

1. Inform private landowners of existing land-use incentive programs. Incentive programs that can be used to promote conservation of bald eagles are listed in Table 2 (following page). FWC staff will work with owners of private lands who wish to manage their lands for the benefit of bald eagles to determine the most appropriate incentive programs.

2. Inform private landowners of opportunities to sell conservation easements around bald eagle nests on their properties. A developer whose activity is not conducted consistent with the FWC Eagle Management Guidelines (page 23) may elect to purchase a conservation easement around an eagle nest offsite or other suitable bald eagle habitat as a conservation measure. This action will provide another landowner the opportunity to be compensated for permanently conserving a bald eagle nest or nesting habitat.

3. Work with local governments to encourage expedited permit-review and/or reduced development-review fees in exchange for voluntarily following the FWC Eagle Management Guidelines. The FWC recommends that developers who voluntarily avoid potential disturbance of bald eagles by following the FWC Eagle Management Guidelines be granted financial incentives or expedited project review. This recommendation will require the cooperation of local governments.”

The Florida FWCC Plan is now only in PROPOSED form, as its implementation is dependent upon the agency receiving adequate funding to conduct surveys, monitoring and enforcement activities. It will rely on strong cooperation, not only with landowners, but local and county governments, especially during the permitting process. Assuring compliance with these proposed measures will be a daunting task, even though they have become less restrictive over the years. Birders, indeed all citizens, should become familiar with these regulations and track the success of state and local officials in abiding by them. We recommend a full reading of the Plan. Here are a few excerpts.

“The National Bald Eagle Management Guidelines (USFWS 2007b) recommend the establishment of a single buffer zone 660 feet or less from the nest, depending on the presence or absence of existing activities (of “similar scope”) and the visibility of the activity from the nest. The guidelines also recommend minimization measures to reduce the potential for human activities to affect nesting bald eagles. When the bald eagle was listed by the USFWS as threatened, the recommended buffers around bald eagle nests were larger than those now adopted under the National Bald Eagle Management Guidelines (USFWS 2007b). The Southeastern Bald Eagle Habitat Management Guidelines (USFWS 1987) recommended against most activities within 750 feet of an active or alternate bald eagle nest (the primary zone), and added a suite of seasonal recommendations for activities up to 1,500 feet (the secondary zone).

“The USFWS and FWC have approved the installation of infrastructure and external residential/commercial construction within the secondary zone (750–1,500 feet) of bald eagle nests during the nesting season in Florida since the mid-1990s, with the provision that monitoring be conducted to evaluate the response of the eagles to authorized activities. These joint monitoring guidelines were formalized in 2002 to ensure that nest monitoring was conducted consistently, and to serve as a database for evaluating the ongoing and future changes in management recommendations. Results of this monitoring indicate that actions that occurred in the secondary zone were not likely to have a direct negative impact on bald eagles. The Bald Eagle Monitoring Guidelines subsequently were modified on three occasions to obtain data used to evaluate eagles’ response to the revised buffer-zone distances already implemented in Florida and incorporated into the National Bald Eagle Management Guidelines (USFWS 2007b) and to reflect current USFWS policy and regulatory changes in Florida. Initial review of the information in these more recent monitoring reports suggests the current USFWS guidelines are appropriate.

“Some bald eagle pairs in Florida tolerate disturbance much closer than 660 feet from the nest, and the behavior of eagles nesting close to or within developed areas seems to be increasing in Florida. Bald eagle use of urban areas is a relatively new event, and the long-term stability of urban eagle territories has not been documented fully. Although some eagles have demonstrated tolerance for intensive human activity, this does not mean that all eagles will do so (Millsap et al. 2004). A minimum of five years of post-impact data is needed to study the long-term effects of development within regulated nest buffer zones (Nesbitt et al. 1993). Both studies described above (Nesbitt et al. 1993, Millsap et al. 2004) recommended retaining buffer zones around bald eagle nests. Therefore, the conservation of active or alternate bald eagle nests and the retention of recommended buffer zones (USFWS 2007b) are recommended to sustain the bald eagle population in Florida at or above its current level.”

The proposed regulations are followed by a Permitting Framework, dated April 2008.

“To advance the conservation goal and objectives of this management plan, the proposed regulations listed above and this Permitting Framework are intended to assist land-use planning to minimize the potential for certain actions to disturb or “take” nesting bald eagles. This Permitting Framework clarifies (1) those activities that are not likely to result in a “take” or disturbance of bald eagles, and (2) those activities for which permits are available to assure compliance with the rules. A FWC Eagle Permit is not required to conduct any particular activity occurring near a bald eagle nest, but such a permit may be necessary to avoid liability for “take” or disturbance caused by the activity…

“…Unless otherwise specified, this section provides guidelines for activities that occur within 660 feet of any active or alternate bald eagle nest. The framework does not apply to lost or abandoned nests. An active nest shows evidence of breeding by a bald eagle pair during the current or most recent nesting season. An alternate nest has been used for nesting during the past five nesting seasons, but was not used during the current or most recent nesting season. An abandoned nest has not been used for nesting for more than five consecutive nesting seasons. The recommendations in the FWC Eagle Management Guidelines (below) no longer apply to abandoned nests, but the nest itself cannot be altered. A nest is considered lost if the nest tree is destroyed, or if the nest is destroyed by natural causes and is not rebuilt in the same tree within two nesting seasons. The USFWS (2006b) recommends protecting lost nests for three years, but the FWC uses a two-breeding-season period because this duration has been in place in Florida for several years. Future research on nest reactivation may provide information to justify revising these recommended protection periods…”

The Plan includes clear restraints on construction-related activities within 660 Feet of an Eagle Nest. Protection of native pines is encouraged. One concern I have is that it appears that eagles in more developed parts of Florida may, in the absence of native pine trees, adapt to exotic trees such as the Australian Pine, as was the case with “our” bird:

“For projects that receive a FWC Eagle Permit, the following minimization efforts may be required:

2. Avoid construction activity (except those related to emergencies) within 100 feet of an eagle nest during any time of the year except for nests built on artificial structures, or when similar scope may allow construction activities to occur closer than 100 feet.

3. Avoid the use or placement of heavy equipment within 50 feet of the nest tree at any time to avoid potential impacts to the tree roots. This minimization does not apply to existing roads, trails, or other linear facilities near an eagle nest, or to nests built on artificial structures.

4. Schedule construction activities so that construction farther from the nest occurs before construction closer to the nest.

5. Shield new exterior lighting so that lights do not shine directly onto the nest.

6. Create, enhance, or expand the visual vegetative buffer between construction activities and the nest by planting appropriate native pines or hardwoods.

7. Site stormwater ponds no closer than 100 feet from the eagle nest, and construct them outside the nesting season. Consider planting native pines or hardwoods around the pond to create, enhance, or expand the visual buffer.

8. Incorporate industry-approved avian-safe features for all new utility construction

We emphasize our concern that the ability of State officials to monitor and enforce these proposed regulations under the pressure of expanding land development is entirely dependent upon adequate funding, and will require the cooperation of local officials. During the nesting season, even more frequent observations will be necessary:

“The Bald Eagle Monitoring Guidelines (USFWS 2007d) recommend monitoring an eagle nest if construction activities occur within 660 feet of the nest during the nesting season (1 October–15 May). These federal guidelines standardize the method for gathering data to evaluate eagle responses to activities that may cause disturbance. The guidelines are designed to: (1) describe normal nesting behavior of bald eagles; (2) identify specific behavioral responses of adult and young eagles that may warrant cessation of development activities; (3) propose the type and level of monitoring necessary to detect a change in normal eagle behavior; (4) prescribe a procedure for reporting to the USFWS and the FWC the observations that may be used to halt or modify construction activities; and (5) provide data to the FWC to evaluate the effectiveness of the current FWC Eagle Management Guidelines. The FWC has adopted the Bald Eagle Monitoring Guidelines (USFWS 2007d). To ensure compliance with these guidelines, the FWC may conduct random spot-checks of projects that are following the guidelines, as resources allow. The information obtained from these monitoring efforts may provide additional insight into the tolerance of bald eagles to human activities near their nests.”

This Brown Anole, on our back patio, was a willing subject:

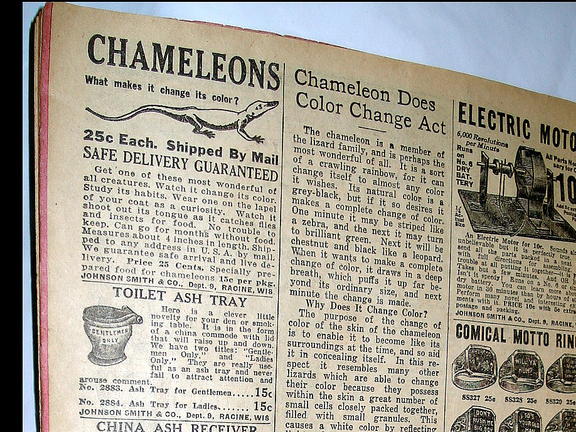

As a kid in the mid-1940s, I was fascinated by the idea of having a “chameleon” as a pet. My desire began when I read an enticing advertisement in a well-worn Johnson Smith Catalog. Among the ads for novelties, magic tricks, fake mustaches, midget Bibles and miracle cures, were those for two exotic pets.

The first was for horned toads, “Most interesting pets– amusement by the hour,” for 25 cents each, “By Mail, Postpaid. Safe Live Delivery Guaranteed.” According to the ad, “The horned toad can live for a very long time. Just how long, nobody seems to know.”

The second, for “Chameleons” also 25 cents each, really captured my imagination. “Watch it change its colors. Study its habits. Wear one on your lapel as a curiosity… No trouble to keep. Can go for months without food… Also grows a new tail.” While the text described a true chameleon (mainly from Africa and Madagascar), the illustration was that of a green anole, a lizard native to the southern states. For 10 cents more, postpaid, you could purchase a little collar and chain with a lapel pin.

Detail from page in old Johnson Smith Catalog:

Well, my Mom never let me buy either. Some of my friends did wear the little green lizards on their shirts, and one kid disrupted our classroom by exhibiting it there. They were so popular that I later found an escapee living on the big crabapple tree out in the back of our New Jersey home, quite north of its expected range.

If you have not been following these posts, you can read the Short Sad Saga of a Texas Horny Toad that I would later (in 1950) ransom (at great cost) during the Boy Scout Jamboree in Valley Forge, a feat that overshadowed President Truman and General Eisenhower’s addresses to our gathering.

When I was transferred to New Orleans in the 1960s, we found our yard to be full of green anoles. We also had some, along with fence lizards, at our next home, in Dallas. When we moved to Florida, I expected to see them here as well. Some green anoles are present in many nearby parks and in the Everglades, but they are losing to competition from the brown anole, an invader from Cuba and the Bahamas. So far I have seen only brown anoles on our property.

Am still experimenting with my new telephoto lens (Canon EF 300mm f4L IS USM). The macro setting worked for the anole portrait above, using autofocus. Attempting flight shots, but the field of view is restricted and it is difficult for me to get the birds in the view finder. The autofocus usually does not work under these circumstances, as the subject is too small. Most of my shots show only blue sky, usually out of focus. The following two attempts were partially successful; both required manual focus.

A Least Tern hovers over the lake. Judging from the vector they fly after catching fish, they may be nesting on the roof of a nearby strip mall.

This Anhinga was almost a speck against the blue sky. The image stabilized lens helped me get a sharper image at this distance. I set the manual focus on infinity.

The above detail of scanned page from an old Johnson Smith catalog is from:

http://flickr.com/photos/oldcatalogs/sets/72157604630668819/show/

Posted by: Ken @ 11:09 am

These photos were taken at a wildlife drinker by remote cameras in Coyote Canyon, just south of Albuquerque on the west side of the Manzanita Mountains, a testing area for Sandia National Laboratories. They were originally e-mailed by an employee of Sandia Labs, are copyrighted by the owner and reproduced here for educational purposes. Note dates and times of the photos.

Not just one, but two mountain lions. My guess is that one of them is a female and the other is her year old cub, as adults avoid each other except, briefly, during the mating season, which is usually in the winter:

On the subject of mountain lions, at the end of this post is a newspaper account of an evening attack on a 5 year old boy that took place this past week in the Sandia Mountains at Balsam Glade, one of my favorite spots (in the daytime). Happily, the child is expected to recover despite suffering several deep lacerations.

Birders have also reported sighting these big cats at Capulin Spring, which is just above the location of the attack. Click for a scrolling panoramic view from the overlook at Balsam Glade (requires Java).

Here, a striped skunk and a fox compete for drinking rights. Gray foxes are the most common montane fox species in Central New Mexico, but the shape of the fox (proportionally shorter legs, longer ears and longer tail) and the lack of a dorsal black stripe on its lower back and tail suggest that it may be a kit fox. The latter species may favor open areas such as these Manzanita foothills. However, I welcome other opinions as to the identification of this canid:

Again, this fox has very large ears and distinct muzzle markings that may characterize it as a kit fox:

Prey species such as these six mule deer also visit the watering hole, reminiscent of Africam:

Coyotes in the morning…:

…and a Black Bear in the dead of night:

While we were staying at our second home in Illinois last month, a full grown cougar (aka mountain lion, panther or puma) was shot by police in downtown Chicago.

Mountain lion sightings, though infrequent, are not unusual in the Sandia Mountains. One morning I listened to a local Albuquerque radio station traffic helicopter reporter tracking a mountain lion as it walked down the middle of Tramway Boulevard at rush hour. While we lived in Cedar Crest, one visited our subdivision with its cub, and another enjoyed basking early on winter mornings in the warm pavement of a tennis court at a nearby residential boys’ school. Cougars have benefited by the discontinuance of bounty hunting, although in New Mexico, they are still hunted with dogs during hunting season.

Interesting information is available at this site, which includes some important advice about how to avoid an attack.

Mountain Lion Attacks On People in the U.S. and Canada

“[I]ncreases in apparently mountain lion sightings have led to general hysteria over mountain lion attacks, and the common conception that something has changed in cougar behavior. However, an extremely simple analysis of the data shows that nothing has changed in cougar behavior at all. The increased number of attacks is explained simply by the increase in the number of people, and the rebound in cougar populations after bounty hunting ceased…”

If you happen to cross paths with a black bear in the wild, it is best not to look it in the eye, and slowly retreat. Bears tend not to be easily intimidated. We had one in our back yard that had a cub with it. When I started banging pots and pans, she just stared back at me,

“The general advice to avoid being eaten by a mountain lion is to travel in groups. If you encounter a mountain lion by yourself or with your children, stop, make yourself look as big as possible, and pick up small children and put them on your shoulders to make you appear even larger. Aggressively defend your position. The idea is to deter their attack by making them think that it isn’t going to be easy for them.”

Monday, May 19, 2008

Animal Attacks 5-Year-Old in Sandias

By Jeremy HuntJournal Staff Writer

© ABQJournal.com and Albuquerque Journal

It was a scream, his father said later, that you never want to hear.

Five-year-old Jose Salazar Jr. walked around a bend as the family was hiking Saturday evening on the Balsam Glade Nature Trail in the Cibola National Forest. He was momentarily out of sight of his family, 20 to 30 feet behind him, when he screamed.

A big cat, most likely a cougar, had tackled Jose and was batting at him, and when Jose’s parents rushed forward, the cat picked the boy up by the neck, dragged him down the mountainside and was only stopped by a fallen tree…

State Game and Fish Department officials, however, said Sunday afternoon they weren’t sure what kind of animal had attacked little Jose. A veteran tracker and his dogs had gone to the trail Saturday shortly afterward and were unable to find signs of a cougar…

The boy, shown pictures brought to the hospital by Game and Fish, identified the animal as a “big cat.” So did his father, although Charlotte Salazar said it looked like a large bobcat…

For the full story, see: URL: http://www.abqjournal.com/paperboy/text//news/state/307308nm05-19-08.htm

We arrived home from Illinois to Florida to find that Northern Mockingbirds were rearing three chicks in an ornamental planting just outside our front porch and next to our garage door.

This is the third year that the birds have built a nest in almost the same spot (the small opening at about 9 o’clock in the upper globe of the topiary, with a bit of straw protruding. It wisely faces to the north):

When I pointed the camera her way, the parent immediately swallowed a large dragonfly that it was bringing to the nestlings. Perhaps this is an evasive maneuver to draw attention away from the fact that a nest is nearby.

These views of two of the chicks were about the best I could manage, as I did not disturb the foliage around the nest and did not want to keep the parents away for very long (click on thumbnails for larger images):

Heat and lots of smoke from the fires in the Everglades have kept us pretty much inside and breathing conditioned air. Our lake is almost 4 feet below the high water mark. Itching to try out my new 300 mm image-stabilized lens, I have found only a few subjects.

Except for a wary Green Heron, long-legged waders have abandoned our lake. The Least Terns are fishing actively and appear to be carrying their catch to nesting sites, perhaps on the roof of of a nearby strip mall. So far, my attempts to catch them in flight have captured only pictures of a smoky blue sky.

Following the massive die-off and two years of almost no reproduction, the local Muscovy Ducks on our lake are again hatching out young. There are three active broods of 10-12 ducklings each.

Mama duck leads her ducklings out of the lake. Image stabilization has taken the shake out of my hands!

This shot, taken with auto focus at about 30 feet from the group of ducklings, shows the depth of field to be quite limited. Only the center-most duckling is in sharp focus. My manually focused shots of these moving subjects were all out of focus (lack of skill or bad eyes?):

|

BirdBlogBytes |

|

| Save Our Boreal Birds | The Boreal Forest is a vitally important breeding ground that supports more than half of the North American populations of over 100 bird species, and it is steadily being carved up by unchecked development. |

| Audubon Action | Petition US government to minimize ecologic impact of Border Wall |

| BirdChaser | Top Ten Ways to be a Better Birder |

| It’s a Bird Thing | Judy’s essays on New Mexico birding. Makes me miss the place even more! |

| Born Again Birdwatcher | John updates the schedule of BirdNote Podcasts |

| Aimophila Adventures | Rick Wright goes “birding in the buff” (sans binos) |

| Bird Watchers Digest | Ten Ways to Help Nesting Birds |

Posted by: Ken @ 1:45 pm

This path in Hawk’s Bluff Park was warbler-rich:

An astronomer defines spring rather precisely. In the Northern Hemisphere, spring begins with the vernal equinox, usually March 21, and ends with the summer solstice, usually June 21. In South Florida, spring, as defined by the appearance of flowers on the trees, starts creeping up around early February, and ends with the rains of June and July. Ask a birder when spring migration begins, and you will get many answers, depending on where the birder lives and her particular interests. In temperate areas, raptors begin arriving in early March. Flocks of swallows may be seen in April. When I visited the Arctic tundra during the first week of June, many shorebirds were just arriving on their nesting grounds.

To me, here in Illinois, as in my childhood home of New Jersey, spring means the time of arrival of flocks of warblers. I remember them coming in just as the tree buds began to burst open in early May. Myrtle Warblers (as we called the eastern race of theYellow-rumped species) appeared earlier, as if to increase our sense of anticipation of the other species. The trees leafed out during the next couple of weeks, and the warblers became more elusinve, and finally disappeared.

The older granddaughter enjoys the swing sets at Hawk’s Bluff Park, to be dedicated this Saturday:

As she studied a Robin through my binoculars, she exclaimed: “These make my eyes really big!”

A new city park is opening near us, along Mill Creek in Batavia, Illinois. Called Hawk’s Bluff Park, it has been a pretty good migrant trap. We mentioned our first visit in our May 2 post (the Canada Goose at the overlook is still incubating). During brief visits the past few days we have seen a surprising number of bird species. Aside from the common resident birds, we have been treated to 4 Vireo species (Blue-headed, Warbling, Red-eyed, Yellow-throated), 4 flycatchers (Eastern Kingbird, Eastern Phoebe, Eastern Wood-Pewee, Great Crested Flycatcher), 4 woodpeckers (Red-bellied, Red-headed, Downy, Northern Flicker), Swainson’s Thrushes, Baltimore Orioles, Rose-breasted Grosbeaks, Scarlet Tanagers, and 9 warbler species (Yellow-rumped, Yellow, Nashville, Black-throated Green, Chestnut-sided, Blackburnian, Magnolia, Black-and-White, American Redstart). Nearby, we also saw Blue-winged Warblers and Common Yellowthroats.

Warblers are getting harder for me to see. Yes, cataracts are forming, and floaters are darting around, but it is not only a matter of dim vision. With climate change and degradation of tropical wintering and boreal breeding habitats, many warbler species are becoming scarce. As measured by the blooming of shrubs and trees, spring has actually been arriving in the northern half of the United States about 8 hours earlier each year since 1982. The trees are leafing out sooner, giving the warblers better hiding places. This all adds up to a spring that seems now to be much shorter than those of my youth.

In a sense, this Illinois spring has been one of my longest in recent memory. We have lived in the southern and southwestern states for over forty years. A few times we have made quick spring trips to Cape May or northern New Jersey at about the right time, to enjoy a day or two of warbler watching, sandwiched between visits to family and friends. This spring has been different. We arrived here in mid-April. There are easily accessible birding habitats which, despite the limitations imposed by weather, family and social obligations, have provided us with almost daily opportunities for an hour or two of birding. Now it must end abruptly, not only because the forest canopy is closing in, but because we must return to Florida for a while.

Don’t get me wrong– I don’t hate Florida. In fact, the winters are delightful, and the Everglades are right at hand. What I miss in Florida is the drama of seasonal change. I still have a snow shovel hanging in the garage. There has not been a measurable snowfall in our area. In fact, the only time snow was ever seen was on January 19, 1977, at about 7 a.m. EST, when a few flurries were reported around Miami. However, my snow shovel has come in handy as a dust pan a few times when I swept out the garage or patio.

This Scarlet Tanager has its usual bright red plumage replaced by bright orange. At first I thought it was an oriole of some sort, but quickly noticed that the heavy bill and lack of wing bars characterize it as a Scarlet Tanager. The Sibley guide illustrates this color variant:

Properly orange Baltimore Oriole:

BONUS FROM GRANDPA: Las dos Nietas riding ponies on their joint (3rd and 4th) birthday party: