Posted by: Ken @ 8:02 am

The Royal Palm is often acclaimed to be the most attractive palm tree in the world. Reaching up to a hundred feet in height, it inspires descriptors such as majestic and indeed, aristocratic. Native to southern Florida, the Caribbean and parts of Mexico and Central America, it is remarkably resistant to hurricane force winds. Their leaves release easily in strong winds, which helps keep them from being blown down. Their trunks widen to adult size before they start to grow upward, about a foot every year. Like the tree rings of woody trees, variations in diameter of their trunks provide a record of years in which they may have been stressed by drought or disease, bulging out in good years and narrowing down in years when growing conditions were poor.

What is wrong with this picture? Look closely at the next photo of the closed and unpaved section of roadway that leads into the water conservation area next to our Florida subdivision. To the eye of the landscape designer, this scene is terribly defaced by the topless palm trunk just past the curve. The human mind seems to crave symmetry and order. A dead tree disturbs that order.

Funding and logistical issues have delayed completion of this road, which will one day become a major thoroughfare connecting I-75 with US-27. For more than a dozen years, these Royal Palms along the roadside berm have withstood several hurricanes, standing tall even after winds stripped off nearly all their leaves. They endured the brutal cold of two especially bad winters, when the mercury dropped into the low 30s. About three years ago, the fronds of this particular tree began turning brown and failed to thrust up a central shoot. For the past two years it has stood, de-crowned and lifeless.

But oh, that tree was so beautiful to the eye of a flicker that drilled into its soft core and made it a home for one summer.

In the fall, starlings took over from the flicker…

…until a kestrel showed up and became master of the property for a whole winter.

The kestrel liked to sit on the front porch of the old woodpecker hole.

The kestrel felt right at home, stretching his wings in the early morning light.

Blue Jays were never happy about their new neighbor, and they worried the kestrel endlessly.

Last month, a little yearling doe walked right by the tree and its transient tenants without noticing how out of place it looked, with its scarred trunk and missing greenery.

She pranced across the street in front of me, spirited and full of life…

…and sprinted past me, down the other side of the road.

This week I found the nest tree, shattered and pinned down by its young successor.

Across the street, awaiting its fate, another topless tree hosted a Red-bellied Woodpecker.

The woodpecker did not budge as the bobcat tractor moved in to do what it had to do.

Why should it bother me? It was only an old dead tree.

Posted by: Ken @ 9:54 am

Book Review: Birding Hotspots of Central New Mexico.

Judy Liddell & Barbara Hussey

W.L. Moody, Jr. Natural History Series

Texas A&M University Press

Many birders are familiar with Judy Liddell’s popular blog, It’s a Bird Thing. Judy’s blog entries often describe her local trips with the Thursday Birders, a dedicated group of Central New Mexico Audubon Society members who get out to interesting places every Thursday morning. The current schedule of Thursday Birder and other CNMAS field trips may be found at this link.

Most of the Thursday Birder excursions are in or around the city of Albuquerque for a half day, making it easy to fit them into a busy schedule. Reading her narratives brings me back to the eleven years I lived in New Mexico. (Please don’t ask why I ever moved to Florida!)

Here are a few birds I photographed in my back yard, located on the east side of the Sandia Mountains just outside Albuquerque. I put a little 2 megapixel point-and-shoot camera up to my spotting scope and shot through the glass of our living room. The quality of these early images may be poor, but the memories they elicit are vivid!

Williamson’s Sapsucker

Cassin’s Finch

Pinyon Jay

Blue Grosbeak

Judy is active in Central New Mexico Audubon Society. In addition to leading CNMAS bird walks, she serves as Vice President and Program Chair. She also is Secretary of New Mexico Audubon Council and is a bird monitor for the Rio Grande Nature Center.

With fellow birder and experienced birding guide Barbara Hussey, Judy has co-authored Birding Hotspots of Central New Mexico. In addition to long and dedicated service for the Rio Grande Nature Center, Barbara is a former President and Board member of CNMAS, and one of the founders of New Mexico Volunteers for the Outdoors.

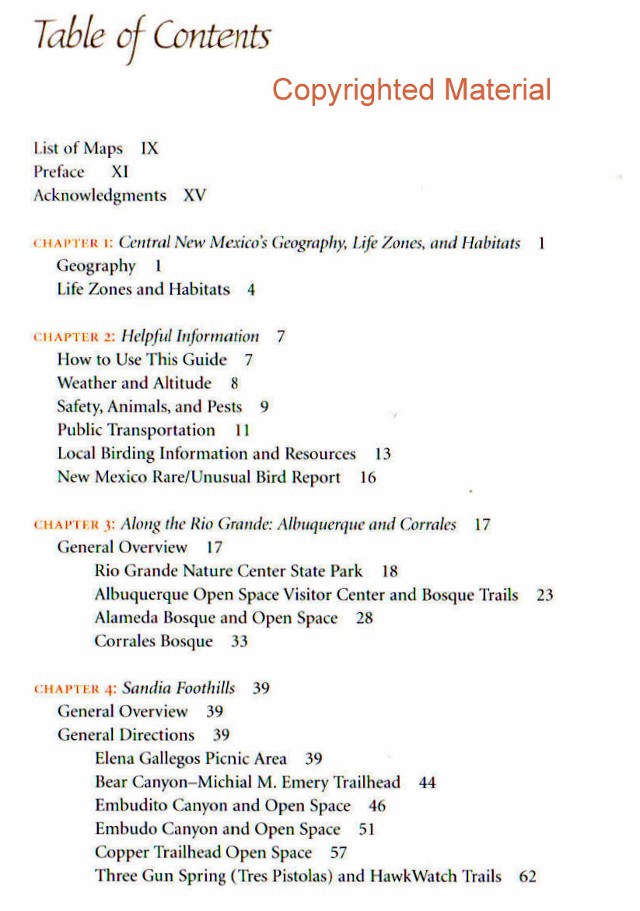

This new site guide draws upon the authors’ familiarity with six clusters of the 29 very best birding locations within easy driving distance from downtown Albuquerque. Sample page views:

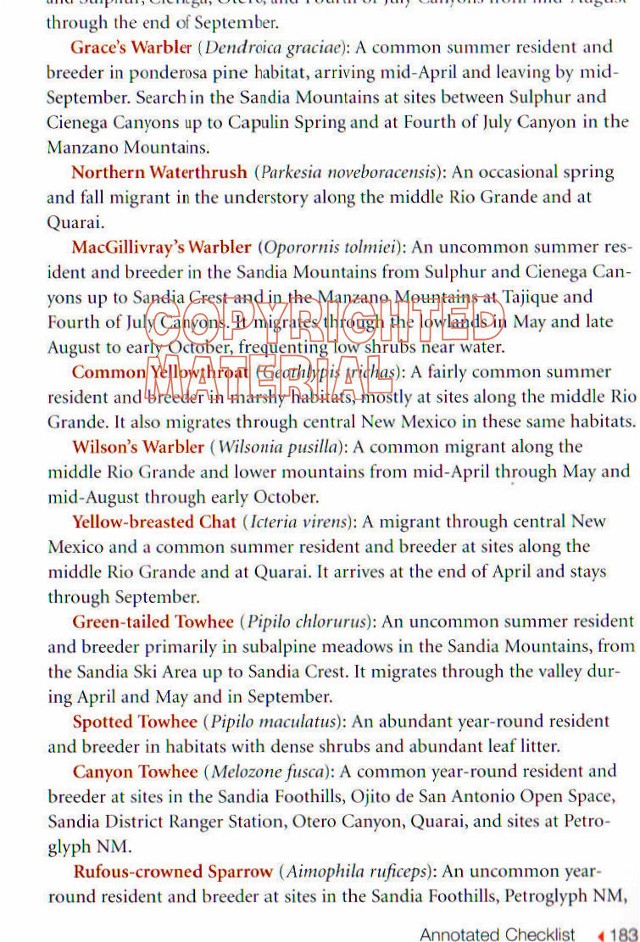

Each of the concise site descriptions stands alone, thus avoiding cross-references and conveying a marvelous sense of place. This assures most efficient use of the visitor’s time– by suggesting the best way to follow a trail, providing locations of the nearest rest rooms, drinking water, lodging and gas stations, and even spots for a picnic lunch. An annotated checklist links species to the best places to see them, and there are many colored photographs that enhance the descriptions of each hotspot.

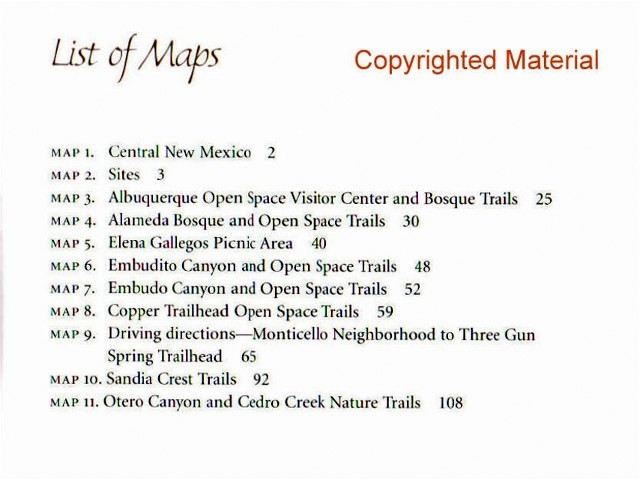

Eleven detailed maps are provided

Road and trail conditions and elevation changes are carefully noted, as are hours of operation, any entrance fees and proximity of public transportation if available. Particular hazards are pointed out as may be necessary, as well as wheelchair accessibility and obstacles for those with limited mobility. At some sites, the visitor will know what time of day is most favorable for birding, and where to get the best views when the trees are bare or fields are flooded. Nearly a dozen maps complement site-specific driving directions that all start from the intersection of I-40 and I-25 in the heart of Albuquerque.

There is a strong emphasis on how to most efficiently locate target species, some of which may be found almost exclusively at one or a few of the hot spots. All of the expected species are listed in an annotated checklist that references only the best locations for finding them.

Unlike some bird finding guides, the text is not cluttered with aging reports of rare and unusual birds. Instead, the reader is sensibly advised to consult the latest eBird and rare bird alerts before setting out. Nearly all of these locations are already indexed by name in eBird.

The flaps of the sturdy softback cover can be conveniently used as bookmarks. They contain more information about the the book and its authors:

Whether planning an extended trip or a few hours’ escape from a business meeting, birders with all levels of experience will find Birding Hotspots of Central New Mexico an invaluable traveling companion.

Posted by: Ken @ 2:11 pm

With good reason, Alaska usually comes to mind at any mention of Bald Eagles. Yet, it surprises some people to learn that, in the lower 48 states, breeding Bald Eagles are most numerous in Florida and Minnesota. In 1990 there were 535 breeding pairs in Florida, and 437 in Minnesota. The number of Florida breeding pairs rebounded rapidly to 1,102 pairs in 2001, then plateaued at 1,133 in 2005. In the meantime, Minnesota’s population climbed slowly at first, to 681 pairs in 2001, then shot up to 1,312 pairs in 2005, surpassing the Florida population.

This US Fish and Wildlife Service graph illustrates the recovery of breeding Bald Eagles in the lower 48 states since DDT was banned in the early 1970s:

In an earlier post, I described why the numbers of Bald Eagles in the more northern of the lower 48 states increase during summer and early autumn, due not only to newly fledged eaglets, but to the influx of more southern eagles. The Florida birds perform an interesting “reverse” northward migration after the breeding season. It is hypothesized that this contrary behavior is caused by another sort of “migration,” namely the vertical movement of the eagles’ main food source.

As Florida’s lakes heat up, the fish seek cooler temperatures in deeper water. Radio tagging of Florida eagles has shown that many follow the cooler water into the northeastern coastal states. Chesapeake Bay is a popular summer and fall gathering place for the Florida population.Immature birds tend to wander more widely than adults, with some even ending up in Canada. Conversely, North America’s northernmost Bald Eagles move south with the approach of winter, seeking open water as the larger lakes freeze up.

Alaskan eagles are, on average, heavier than those in Florida and have longer wings. I photographed this one in Soldotna, Alaska, along the Kenai River:

We have a particular interest in Bald Eagles, as we have been involved in protecting a recently discovered nest in our south Florida neighborhood. During the first week of October, 2011, Mary Lou and I were pleased to see that both members of the pair had returned to the nest:

They were already rearranging the nest materials:

On October 12, 2011, I photographed one of the pair at sunrise, flying from the nest area in the general direction of the largest lake in our subdivision:

On October 16, 2011, the female was sitting high on the nest…

…while her mate (judging by its slimmer build and slightly smaller size) roosted in a nearby Australian Pine:

We first became aware of the local pair of eagles on December 4, 2007, when I photographed them mating on the rooftop of a house just across the lake from our home:

As there had not been a record of an active Bald Eagle nest in Broward County since several years before DDT was abolished in the early 1970s, I reported the sighting on the Tropical Audubon Society’s Web page, and birders in neighboring Pembroke Pines had a general idea of where they might be breeding. In March, 2008, Kelly Smith, a local middle school teacher found the nest, located only about 150 feet from a busy boulevard. It contained one nearly full-grown eaglet.

This photo of “P. Piney One” was taken by Kelly Smith on March 15, 2008 and is reproduced here with her permission:

This pair of eagles has returned to the same nest each year, successfully raising and fledging two chicks in 2009, three in 2010, and two more this past spring. The nest is about 50 feet high in an exotic Australian Pine tree with smaller trees blocking most of the view, so we only get distant looks.

On December 11, 2008, both adults are shown sitting on the nest, only two days before the first of two eggs was laid::

Local middle school students conducted a nationwide poll that chose names for the two eaglets, “Hope” and “Justice:” They hatched on January 15,2009. Here they are, squabbling with each other at exactly one month of age. Hope, the older and larger, is on the left:

The eagle nest attracted a great deal of attention, and crowds of up to 100 people came to see the antics of the eaglets, causing traffic hazards as they stopped on the roadway and parked illegally.

The Mayor took an interest in the nest, which is located on City of Pembroke Pines property, and he announced his intention to declare the site a City Bald Eagle Sanctuary, and took measures to protect both the eagles and observers.The City has amended its planning documents to pave the way for an ordinance that will provide safeguards against disturbance of any eagle nest in the city. This past summer, major resurfacing of the roadway and construction of a sidewalk were suspended in the area of the nest during the eagles’ breeding season (May 15 - October 1).

I photographed these three eaglets on March 2, 2010. The Middle School students’ poll resulted in them being named Chance, Lucky and Courage. All three fledged successfully:

The eagles returned in October, 2010 to refurbish the nest, and eggs were laid around December 11. ( * See end note about how we estimate the time of egg laying and hatching). On January 23, 2011 at the age of about 9 days, this chick was first seen, peering over the nest rim:

Here, it waits as its parent tears off a bit of food. A younger sibling was not yet visible from the ground:

The Parent eagle feeds the chick :

This was about as good a view we could get from 150 feet. Vegetation now makes viewing much more difficult. Plans for a nest camera did not materialize:

Here is the older of the two eaglets, on February 3, 2011. Much of her natal down has already disappeared:

At one month old, on February 15, 2011, the down had been reduced to a fuzzy cap:

Less than two weeks later, on February 27, 2011, the eaglets looked almost as large as adults. We called them “P. Piney Seven & Eight.” Bald Eagles exhibit sexual dimorphism that starts when they are nestlings, with the females usually considerably larger than males. PP 7 is the larger and was presumed to be a female:

At two and a half months of age on March 23, 2011 they were exercising their wings, preparing for their first flight, which usually occurs when they are between 10 and 12 weeks old. PP7, on the right, has more white underneath than her younger brother:

On March 30, 2011, we found PP8 alone in the nest; PP7 had flown off, but returned within three days to be fed:

On March 30, PP8 was “helicoptering,” hovering in place up to a foot off the ground:

Here, on April 3, 2011, my last shot of PP7 shows her roosting in a tree next to the nest. PP8 was flying back and forth on branches in the nest tree:

*In estimating the timing of the laying of eggs and hatching of the eaglets, we must depend upon clues from changes in the behavior of the adults. The onset of incubation coincides with the laying of the first egg, which is when we suddenly see one of the pair down deep and immobile in the nest. Hatching is a time of excitement, as the parents shift position frequently, peer down into the nest, and they start bringing in prey and tearing off bits to feed the tiny chick. The adults also sit a bit higher in the nest after the first egg hatches, supporting themselves on their wings to form a “tent” to shelter the chick and yet provide warmth to any eggs that have not yet hatched.

Posted by: Ken @ 6:25 am

In an earlier post I described the creation of Chapel Trail Nature Center and its near destruction when vandals set the boardwalk on fire shortly before its planned grand opening. It had been open less than a year when Hurricane Wilma toppled most of the boardwalk. Earlier this month, soon after we returned to Florida from our second home in Illinois, we visited the preserve, located nearby in Pembroke Pines. It was a rather dull morning for birding. There had been plenty of rain, and flood water had diluted out the fish so that the long-legged waders were no longer concentrated there. We started out late and it became progressively more hot and muggy.

The resident Sandhill Crane greeted us at the parking lot…

…and posed next to a fire hydrant…

..but otherwise it seemed that the paraglider overhead and the insects and flowers around us would be the best sightings of the day:

Spiny Orb Weaver:

This photo was marred by a single bokeh that took on the appearance of a full moon, but I decided that it looked in balance with the image of the Swamp Lily:

There were two of these little green-eyed blue-bodied black-tipped dragonflies. about 1 to 1 1/4 inch long– too small to be Eastern Pondhawks, so I at first was not sure of their ID. There is a midge on this one’s back. Interestingly, one species of dragonfly, Sympetrum, has antibodies against its midge parasite (Arrenurus planus). When the midge bites into the dragonfly, its piercing mouth parts turn bubble-like and the parasite dies. Midges are used to control certain insect pests (Reference).

Blue Dasher– look closely to see the midge, or click on the photo to see the note:

A Green Darner rarely perches. This guy would not stop flying, but did hover in place long enough for me to get the center point focus on him. If I had planned this shot I would have increased shutter speed greatly:

The resident Red-shouldered Hawk watched us from it perch in a small tree:

A lone White Ibis flew overhead…

…as did an Osprey:

From the boardwalk, Mary Lou scanned the wetlands :

A Great Egret was nicely back-lit by the early morning sun:

A Green Heron stood on the rail of floating boat dock at the far end of the boardwalk:

Then, the head of a Limpkin appeared above the marsh vegetation (I did not notice the two Purple Swamphens, out of focus behind it and to the right):

The bird flew up and passed directly in front of us on the way to a roost in the small island:

Purple Swamphens seem to get more numerous every week at Chapel Trail. As we walked along the boardwalk, there were 2 to 3 in view at all times. We saw no gallinules or moorhens, which is a bit disturbing– their young are said to be food items for the invasive introduced swamphen:

We also saw a half dozen Eastern Kingbirds:

Many of the Eastern Towhees that breed in far southern Florida have yellow rather than red eyes:

A Common Yellowthroat foraged in the Red Maple leaves, already starting to change color:

The yellowthroat was joined by a Prairie Warbler:

Yesterday morning we got out just before a big rainstorm curtailed our walk. The leaves of the Red Maples had already gone from red to brown. We found that Palm Warblers had arrived in good numbers. They become so numerous during the winter that locals call them “Florida Sparrows.” During fall migration, the brightly colored eastern Yellow Palm Warblers cross paths with the dull western form, and winter more to the west, from northern Florida into east Texas.

This is a representative of the dull Western race, much more commonly seen than the bright eastern form:

Despite the dark skies, this Boat-tailed Grackle’s iridescent coat reflected many hues of blue:

It was starting to drizzle as a Mottled Duck flew overhead:

On the way out, I stopped to photograph a Little Blue Heron that was walking along the canoe dock:

A Marsh Rabbit watched us warily as we exited the boardwalk.. This semi-aquatic race of Cottontail has a darker coat and very short ears:

Posted by: Ken @ 11:07 am

Now that I have become the proud owner of a pair of snake boots, I took up my neighbor Scott’s open invitation to accompany him on a deeper hike into the wetlands adjacent to our homes. This area, located just west of the cities of Miramar and Pembroke Pines, is part of the Broward County Water Preserve, consisting mostly of land that has been set aside by developers to compensate for intrusion upon the historic Everglades by construction of housing subdivisions.

Much of this is land that long ago had been drained and converted to agricultural use, mainly grazing of livestock. Now it is partially surrounded by low levees and managed by the South Florida Water Management District (SFWMD) under supervision of the US Army Corps of Engineers. As part of the Comprehensive Everglades Restoration Plan (CERP), the land was more recently cleared of invasive exotic plants, notably Melaleuca, Australian Pine and Brazilian Pepper. In the portion nearest our home, maintenance appears to have ceased since about 2005, and the exotic Melaleucas are once again spreading into the open wetlands, where they form dense stands.

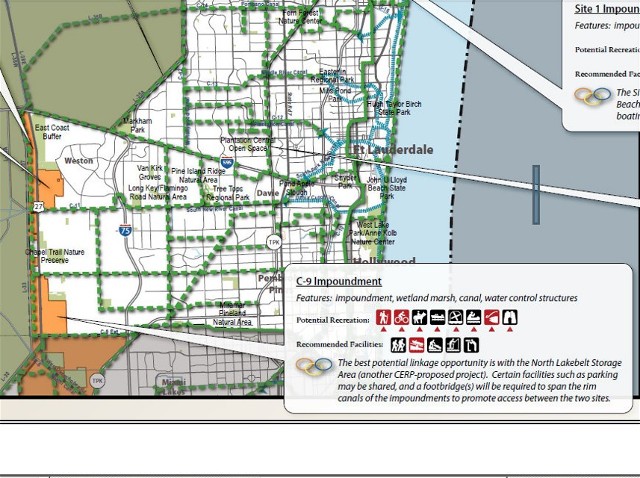

Under CERP, this wetland will be surrounded by higher levees and turned into a huge reservoir to hold storm water overflow from the planned C-11 impoundment to be constructed ten miles to the north, in Weston. The water depths in this planned lake will vary, depending upon rainfall, from zero to four or perhaps six feet. The objective of this impoundment is to limit eastward seepage of Everglades drainage, thus recharging the aquifer and reinforcing the historic north to south flow of the “River of Grass.” Because of funding and logistical issues, construction of the C-11 impoundment would not begin until at least 2015.

Therefore, our local reservoir (designated as the C-9 impoundment) is on hold for at least ten years. From our standpoint, this is good news, as we now enjoy the presence of terrestrial species that will certainly be driven out when the area is flooded. Here is an informative link about CERP, which includes the following map:

Water levels in our disturbed local wetlands weakly imitate the natural cycle of the original Everglades. An extinct quarry forms a large lake that occupies much of the Harbour Lakes portion of the preserve. Summer rains swell the lake and it spills over into the surrounding Sawgrass meadows. Sawgrass is actually a sedge, and it thrives when the soil is waterlogged for ten to twelve months out of the year.

Water now covers the adjacent Sawgrass meadow. The waterway in the foreground will be a dry to muddy trail by late spring or early summer, but is too deeply submerged for our morning jaunt:

Some parts of the wetland are better drained or are at slightly higher elevations, so their shorter hydroperiod (the length of time that there is standing water) favors beds of periphyton*, algae and other plants such as Spike Rush.

*From: Freshwater Marl Prairie

A complex mixture of algae, bacteria, microbes, and detritus that is attached to submerged surfaces, periphyton serves as an important food source for invertebrates, tadpoles, and some fish. Periphyton is conspicuous and is the basis for the marl soils present. The marl allows slow seepage of the water but not rapid drainage. Though the sawgrass is not as tall and the water is not as deep, freshwater marl prairies look a lot like freshwater sloughs.

A Great Egret stands in this marl prairie, which is covered mostly by rushes:

In January, periphyton floats to the surface as the water level recedes:

The areas free of Sawgrass are richer in nutrients and more friendly for wildlife, such as this American Bittern hiding among the Spike Rushes:

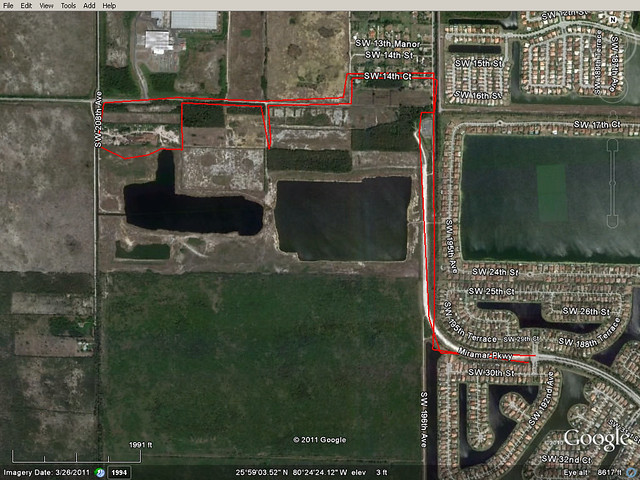

Scott is a “working stiff,” so we met up at 7:30 AM on Saturday. To my surprise he had his little Yorkie, Gordo, on a leash. Gordo was to prove to be a enthusiastic and even useful companion for what turned out to be an ambitious five mile hike. We walked a loop north into Pembroke Pines on the unpaved Miramar Parkway/SW 196th Avenue extension, then cut south and west almost to US-27. At times we found ourselves in water up to mid-shins and sunk into ankle-deep mud. We departed at 7:30 AM and got back around 11:00 AM.

This was our route, beginning and ending at the lower right (SE) corner of the map:

We walked mostly on remnants of old farm roads, which are blocked from vehicular traffic, but often used by recreational ATVs. The cross-country part of our walk was the southern portion of the loop in the upper left part of the map. There, we made very slow progress through a flooded prairie of Sawgrass. We followed animal trails (presumably deer) that tended to make circuits around deeper sloughs and alkali sink holes, but the going got so tough that we considered turning around when we had bushwhacked more than half way to our goal, which was the unpaved portion of SW 208th Avenue that runs north and south (along the far left side of the map). All this time I kept my camera safely tucked away.

As we approached the road we heard dogs barking in the junk yard to the north, and when we finally emerged into the open we were greeted by a pack of eight to ten mixed breed hounds. Thankfully, they were more interested in Gordo, who diverted their attention as we made friendly talk with them and tried to act nonchalant.

Before the dogs actually reached us we encountered a young Cottonmouth in the two-track road (note its bright coloration and yellow tail; older moccasins turn dark with obscured markings) :

I wondered how many snakes we had NOT seen during that part of the hike, and was really happy with my snake boots– except that it turned out that both boots leaked! The walk back was a bit squishy.

A Red-bellied Woodpecker clung to an old telephone pole:

Along the way, a Red-shouldered Hawk monitored our approach before flying off:

Gordo found this pugnacious crayfish along the path. It attacked him, then me as I tried to catch it. They are known to change colors, and perhaps the red reflects its fighting mood (I took it home and it now resides in my aquarium– dull olive brown in color):

Scott and Gordo on this trail, which follows the right of way for Pembroke Road:

Two Painted Buntings flew along the trail in front of us. I only was able to photograph the female, and she was a beauty:

One of a pair of Northern Waterthrushes created a very pretty reflection in a puddle:

Two Yellow-crowned Night-Herons were roosting at the site of last year’s rookery:

Not to be overlooked were this roadside Loggerhead Shrike…

…a White Peacock…

…and a Gulf Fritillary:

By the way, I sent the boots back to the manufacturer, as they were guaranteed 100% waterproof. They have already shipped out a replacement pair. Since they fit well and were quite comfortable (when dry) I will assume my problem represented a sample defect and will withhold any review of the product pending resolution of the issue.