Posted by: Ken @ 1:59 pm

This morning, warblers were hiding in the dense leaves of this “bird thicket,” or moving among the small Live Oaks that run along the right background:

There are a couple of particular problems with birding in the autumn. First, the migrants aren’t singing as they do in the spring. Second, the trees are still loaded with full-sized leaves. I could add “confusing fall warblers,” but only a few actually fit that category. Anyway, you have to see them first before they can confuse you.

This morning was a case in point. Tropical Storm Nicole, or what was left of her, had passed by yesterday, preventing us from taking our “power walk,” which is customarily followed by a little birding if laziness, appointments, shopping or other chores do not interfere. After a day of forced leisure, Mary Lou and I headed out to see if the change in weather had brought any new warblers into our local birding patch.

It’s great to get out early before the wind starts up and the butterflies are still sleeping. Under these conditions, the presence of a bird is easily revealed by the slightest stirring of a twig. Thanks to the fact that we have 20 times more motion-sensitive rods than color-sensitive cones on our retinas, it is quite easy for us to detect such peripheral visual clues, especially if the wind isn’t blowing, and the butterflies aren’t flying about.

“Oh, to be 70 again!” I used to laugh when my Dad would say that. (OK, young folks that don’t want to hear any grousing can skip this paragraph.) For some of us old guys, there are cataracts and “floaters” that add to the fun and challenge of birding. Truth is, time does take its toll and, because they are subjected to greater exposure to UV light, the eyes of mariners and birders are at increased risk of developing cataracts. Of course, genetic and many other factors can contribute to the formation of lens opacities. After I had my right lens replaced, I experienced a shower of dark spots, “floaters,” in that eye. To a non-birder, these would be of little consequence, but for me they can be a real distraction, especially out in the open, when they fly by like birds that demand my attention. They are gradually getting better, but vision in my “camera eye” is not sharp enough to permit me to use manual focus.

Dependence upon auto-focus has drawbacks, such as with this photo of an adult male American Redstart, optimally positioned in good light. I thought I had gotten my best-ever shot of this active warbler.

Well, at least the leaves in the foreground are in good focus:

But butterflies are a greater problem. Here in South Florida, the Zebra Heliconians are the worst offenders. Their striped wings flicker amid the foliage, and they dart here and there willy-nilly.

Zebra (Heliconius charitonius), the State Butterfly of Florida:

Another Heliconian, the Gulf Frittilary (Agraulis vanillae), was also well represented…

…as were richly colored Queens (Danaus gilippus):

I’m tempted to place gnatcatchers in the same category as “distractions,” because all too often a sought-after warbler disappears into the canopy, and out pops a gnatcatcher. However, I’ve often found that other species may congregate with gnatcatchers during migration, and it is a good idea to assume they are not alone.

Blue-gray Gnatcatcher:

Blue Jays deserve respect as well. A bunch of them were calling raucously when we arrived at the “bird thicket.” Sure enough, a Red-shouldered Hawk soon flew into view and disappeared before I could take its picture.

This Blue Jay has completed its molt and is quite handsome:

Enough complaining! True, about a dozen warblers went unidentified, and several Black-throated Blues, two redstarts and one probable Yellow-throated Warbler “got away,” but one Northern Parula was very cooperative.

Notice the color contrast between the legs and feet of this Northern Parula:

We got good looks at several Prairie Warblers…

…the Ovenbird came out of hiding again, to Mary Lou’s delight…

…the Northern Cardinal was as beautiful as ever…

…and, we welcomed our first-of-the-season Palm Warblers. Soon these “Florida Sparrows” will be everywhere until next spring:

When we got back home, a Great Blue Heron (photographed through our back window) was walking next to our patio, intent upon catching lizards:

The birding experience does not have to be perfect to be fun, and anyway, there’s always tomorrow!

Posted by: Ken @ 5:30 am

Saturday Sunrise from our back patio:

The weather report was not encouraging. Storm clouds over the Atlantic coast produced a beautiful sunrise. Optimistically, we set out for nearby Chapel Trail Nature Preserve in Pembroke Pines. Skies were gray and there were occasional misty drizzles as we walked along the boardwalk.

A Red-shouldered Hawk screamed incessantly from the top of a melaleuca in the adjacent pasture. We had no ideas as to what was bothering it.

The light was so poor that I had to brighten up this photo of the noisy hawk:

A male Northern Cardinal contrasted with the gloomy sky:

An Anhinga tried to dry its feathers, but the rain picked up:

We made a hasty retreat to the car just as a downpour began.

The next day, the clouds had lifted and there was less red in the morning sky:

Mary Lou still wanted to make up for missing the Ovenbird. After our pre-dawn “power walk,” we walked out to the birding “patch” next to our subdivision.

She walked ahead of me on the grassy path next to the berm that runs along the unpaved portion of Miramar Parkway (in the background to the west is the wetland, part of the Broward County Water Conservation Area, that we call the ESL “West Miramar Environmentally Sensitive Land (ESL)“:

Two male Black-throated Blue Warblers appeared almost immediately:

They were joined by a male American Redstart:

A Ruby-throated Hummingbird perched nearby:

This immature female Prairie Warbler lacks the streaking that is characteristic of adult birds:

A White-eyed Vireo started singing right in front of us. I captured it in an unconventional pose:

While we were occupied with the vireo, Mary Lou spotted an Ovenbird, then another, lurking in the shadows under the shrubbery. I was delighted when it walked out into the open:

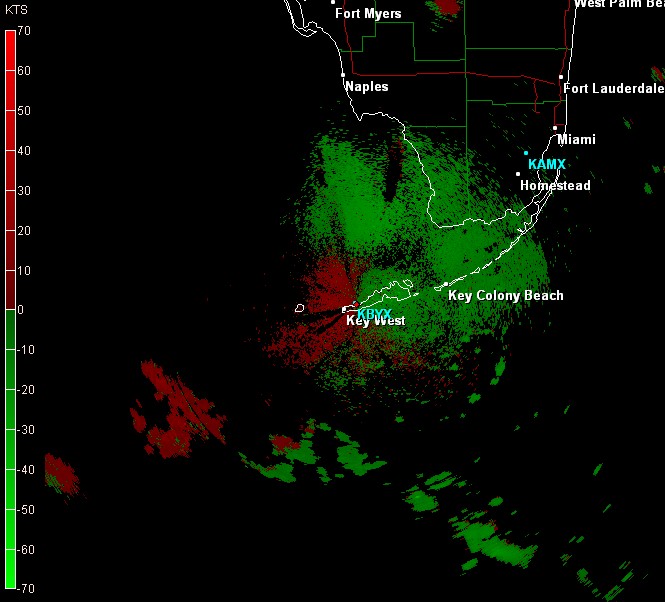

That evening (Sunday) we watched the Key West radar for migrants. A fair number of birds were departing from the lower Florida peninsula in the direction of Cuba. Ominously, they were headed into a line of rainstorms. We wonder how many made it to Cuba that night:

This screenshot shows the direction of the flight as well as that of the storms. Green echoes are moving towards Key West, while the red returns are moving away. It suggests that some of the migrants, just due south of Key West, have either turned around or are being blown back northwards:

Posted by: Ken @ 4:01 pm

Prairie Warbler in flight:

Hoping to get another and better look at the three Bobcats, I walked south past the spot in the trail where I had last seen them. On a previous occasion, the scolding of birds gave away the location of a Bobcat. This time, there was only silence.

As it turned out, my foray along the overgrown path atop the 196th Avenue levee was not a bad idea. Suddenly, several Prairie Warblers put in an appearance. The above was a lucky shot, as I clicked the shutter just as the bird left its perch.

Here is a nicely marked male Prairie Warbler:

This one appears to be an adult female. Prairie Warblers will remain here all winter:

I did not see the sought-after Ovenbird, but one of its cousins appeared unexpectedly as I was photographing two Brown Thrashers that appeared along the path.

I presumed this to be a Louisiana Waterthrush, as i thought it had a very long and conspicuous white line over its eyes, relatively unstreaked throat, and bright bubble-gum colored legs, helping to distinguish it from the very similar Northern Waterthrush. The latter is a more common migrant in South Florida, and has bold streaks against a white breast. Expert opinion leans toward it being a Northern Waterthrush, based upon buffy breast and the fact that the throat has some streaks:

The waterthrush stayed well-hidden in the lower branches, and I was lucky to capture a few images as it briefly stepped out into the sun. In Spring, their songs readily distinguish the two waterthrushes, but this one was silent:

The Brown Thrasher was even more elusive, only providing me with one chance. The harsh morning light and my too-high ISO setting resulted in a badly overexposed image (but I love that eye):

Something odd happened as I was looking across the canal. Two birds that looked to be joined together flew slowly and laboriously across the water, only about 10 feet above the surface. They seed to be struggling just to stay airborne, and sure enough, they slowly descended. When only about 3 feet over the water, one of the birds fell into the water and the other quickly flew away.

The bird in the water was a bit smaller. It splashed for one or two seconds, then lifted off and flew to the shore in the opposite direction. I am quite certain that the larger bird was a Loggerhead Shrike. The smaller was about the size of a larger warbler or vireo (I would say sparrow-sized, but we don’t have any sparrows here this time of year), but I could not confirm the identity of either. Shrikes are known to prey on birds that are almost the same size, so this was probably not unusual. The intended victim was lucky to survive the attack, as shrikes can use their sharp bill to quickly sever the spine of a captured bird.

This Loggerhead Shrike was in the general vicinity of the attacker, and it stood out against the blue sky:

I saw a couple more birds that wore shades of gray. This Northern Mockingbird posed nicely:

A Blue-gray Gnatcatcher was more acrobatic (no, the photo is not inverted):

Another gnatcatcher assumed a more conventional posture:

A small flock of warblers joined the gnatcatcher, including this male Black-throated Blue Warbler:

The female Black-throated Blue Warbler is a more subtle beauty:

Continuing the monochromatic theme, several Black-and-white Warblers gleaned the tree trunks:

One Black-and-white Warbler imitated a nuthatch’s pose:

On the way back, I stopped to study the butterflies. I’m only just beginning to learn about them. At my age it is getting hard for me to remember the names of new animals and plants, and I often have trouble matching them with their pictures in Glassberg’s “Butterflies Through Binoculars.” I welcome corrections from knowledgeable readers.

A Florida Fiddlewood (Citharexylum spinosum), a native verbena, was in bloom with tiny tubular flowers that attracted this Horace’s Duskywing:

The Monk Skipper is similar but much more plainly marked. It is a Cuban species found in the southern tip of Florida, and exotic ornamental palms serve as host plants:

The verbena is host for the White Peacock, a tropical butterfly that ranges into the Florida peninsula, rarely straying up the east coast as far as the Middle Atlantic states. It is one of my favorites:

This Fiery Skipper feasts on the nectar of multicolored Lantana flowers, another Verbena native to Florida, but its larvae eat Bermuda grass:

Posted by: Ken @ 9:24 pm

Last week, I encountered a flock of migrants in a small wooded area in the mitigation wetlands next to our home. I returned from my morning walk with lots of photos. Mary Lou had stayed home and missed the fun. As she reviewed the downloaded images, she seemed less impressed with some of my more colorful finds.

Prairie Warbler:

Red-eyed Vireo:

Mary Lou was most interested when she saw my poor shot of a drab and reclusive little Ovenbird, peering out from the shaded leaf litter:

This photo made her want to re-connect with an old friend. She had missed seeing an Ovenbird the past couple of years (and come to think of it, so had I), until that morning. She actually prodded me to get out early the next day to look for that bird!

As a kid I dreamed about marrying a girl who loved watching birds and didn’t mind getting out early to a landfill, or peeing in the woods. That didn’t happen, that is, until Mary Lou’s “epiphany” when, in 1999 on our first birding Elderhostel in southeastern Arizona, she saw the Elegant Trogon and suddenly started watching birds. I was reminded of that day (How Mary Lou Became a Birder).

I should have welcomed her enthusiasm, but I actually felt a little relief when it rained briefly at around 6:00 AM on Sunday morning. I was ready to veg out, read the paper and watch the Dolphins win their second game (which they did).

The rain stopped, the skies cleared and the sidewalks quickly dried out. At about 7:30 AM we walked the quarter mile along the unpaved western extension of Miramar Parkway to our little patch of recovering Everglades. The developer of our subdivision was required to set this land aside to make up for the scars our homes had inflicted on the great River of Grass. We call our “patch” the West Miramar ESL (for Environmentally Sensiteive Land). Officially, under the Army Corps of Engineers Comprehensive Everglades Restoration Project (CERP), it is part of the extensive Broward County Water Preserve.

We approached the canal that runs along the western border of our development and forms the near side of the ESL, and were struck by the silence, Not even the mockingbirds were singing. Where, on the previous day, warblers had streamed along the line of small Live Oaks aside the road, we saw no birds. As the sun warmed up the trees and the butterflies and other insects started coming alive, a few mockingbirds and a pair of cardinals appeared in the shrubs, and two or three Blue-gray Gnatcatchers moved into the oaks. For almost an hour, we waited for an Ovenbird to stick its head out from the underbrush.

One did appear, briefly, but we had only a tantalizing glimpse of its tail-up profile through the branches (this is an earlier photo):

Mary Lou decided she had better things to do at home and left me there, alone, with the admonition to the Ovenbird that it better not show up right after she left. It didn’t, so I wandered around to the levee that runs to the south along the west side of the 196th Avenue Canal. It is overgrown with tall grasses, so the sight distance along the two-track path atop it is quite limited. As usual, I approached the edge of the path quietly, for it is sometimes used by birds such as Common Ground Doves, as well as mammals, including Marsh Rabbits, Raccoons, deer, and twice, Bobcats.

I was startled to find a good-sized Bobcat, lying across the path, about a hundred yards away:

The Bobcat did not see me immediately, but when it did, it merely got up and slowly walked away down the path, stopping now and then to look back at my immobile figure. Then, I was treated to an even greater surprise– two more Bobcats appeared out of the grass. They were more brightly marked than the first cat, and appeared a bit smaller and leaner. One of them playfully jumped in the air, perhaps chasing dragonflies or butterflies. I assumed they both were cubs.

I never thought to change from automatic to manual focus, so most of my photographs were focused on grass blades that arched over the path between me and the subjects.

This was the best shot of the two cubs I could obtain:

Here is a photo that I believe is the resident female, taken this past February not too far south down the same trail. I had seen and photographed two adults near there the month before– they usually do not associate except at mating time, so she may be the mother of the two cubs I just saw:

Next post: “Looking for Bobcats, finding birds and butterflies”

While we were in Illinois, we learned that a very rare wanderer from Cuba had shown up in Everglades National Park. A Cuban Pewee (Contopus caribaeus), native to the Cuba and the northern Bahamas, and actually rather uncommon on parts of its home range, was heard and then identified on September 5 by Larry Manfredi. It was located at Long Pine Key, a camping ground in Everglades National Park. Only last week, I blogged about suffering “brain freeze” when I encountered an Olive-sided Flycatcher, also a member of the pewee genus Contipus.

This was only the third time that this species was ever recorded in North America, and its first appearance in Everglades National Park. We held out little hope of ever seeing the bird, but it was still there when we returned to Florida. On September 13, Mary Lou and I took the one hour drive down to the Park, arriving at 7:00 AM, just around sunrise. We were soon joined by a few other birders on the same quest.

Larry and other observers had earlier reported re-locating the bird within a fairly small area, at or near Gate 3 just off the road to the campground. The Pewee was said to be more vocal early in the morning, but we heard not a sound. By 8:00 we had spread out along the road, listening and looking, to no avail. Happily, at about that time, Larry himself came by, and within minutes he located the bird. Larry is an experienced expert bird guide. He is very familiar with the Cuban Pewee and was able to pick out its feeble “dee-dee-dee-dee” calls despite the racket being made by mockingbirds, woodpeckers, jays, grackles and numerous singing Pine Warblers. Read his trip report to the Bahamas at this link.

The Pewee was in heavy molt. Its contour feathers were in disarray and new tail feathers were emerging underneath the few remaining old ones. Since molting requires so much energy, it is not uncommon for birds in molt to become more sedentary. Perhaps this accounted for its limited movement during the past week.

Conveniently, the Cuban Pewee posed for us in full sun, just above Gate 3:

Click on this photo for additional views:

My photos are a bit misleading, The harsh morning sun imparted golden tones to a plumage that, to my eyes, appeared more on the side of olive-gray.

We, along with the other newcomers, including a lady who drove in from South Carolina, celebrated our new “lifer.” Back home, this was reason for us to update our spreadsheets of bird sightings. For me, it was the 576th species I have identified in the ABA North American area, and for Mary Lou, her 507th. I started listing my sightings in January, 1948, and it took me 53 years of birding to reach my 507th life bird, a Pine Grosbeak in January, 2001, in New Mexico. Mary Lou attained her mark in only a little over 11 years of birding!

Back in 2003, we saw another “accidental” flycatcher at Bosque Redondo, New Mexico, a Piratic Flycatcher that had been reported in North America only three times previously.

I took this photo of the Piratic Flycatcher with a 2 megapixel point-and-shoot through my spotting scope (click on photo for more details):

Below is a slide show with multiple views of the Cuban Pewee: