Posted by: Ken @ 10:33 pm

It seems that when I go out into the field on a single-minded quest for a target bird, more often than not I am disappointed. For the past couple of weeks, I have wanted to see a warbler. Any old warbler would do. Until I took up photography a few years ago, “see” meant exactly that. More correctly it meant “see and identify.” I must admit that by “see,” I now mean “photograph.”

In the case of migrating warblers in the fall, this sharply narrows down the criteria, even with the help of 10X glasses and a supple neck. Trees are full of leaves and warblers prefer to be high up and on the wrong side of both. Now I have a stiff neck and my cataractous eyes force me to depend upon automatic focus if I want a clear picture.

Of course, some photos seem to be gifts from the “warbler gods.” Last week, this female Chestnut-sided Warbler posed in perfect light, so close by that I had to back off to focus on her. (This image is cropped directly from the RAW file without any other editing)

Why do I now have this compulsion to package birds’ images into files that consist of nothing but ones and zeroes? The world does not need any more bird photos. Birds must be the most photographed natural objects other than babies and waterfalls. If I want to see a great bird picture I can just Google for it.

It should be enough for me to simply take in the great beauty of plumage, song and movement. And it always was, until a 300 millimeter image stabilized lens attached to a 1.4x extender and a progression of three generations of digital single-lens reflex cameras with a monopod and accessory pack were added to the weight I carry into the field. Why do I wish I were carrying this burden when an eagle flies over as I am walking to the supermarket? It is just another eagle, and pretty far away at that.

I will not attempt to answer my rhetorical questions except to say that photography has added an important dimension to my appreciation of birds and nature. For one thing, it has allowed me to start my life list of bird sightings all over. I don’t tabulate them or keep a spreadsheet, but I copy them into a set on FLICKR. My “Life List of Bird Photos” contains 261 images, including some omissions and some duplicates that I must weed out.

Many of the images are poor, and I plan to replace them with better shots if I get them and remember to go back to the photo set. It is less than half way to the total on my ABA area list of species sighted. Of course it sets out an impossible challenge, as I am running out of time to try to match both lists. But the quest goes on, to find new species to add.

As I write this, I realize I have omitted this Yellow-breasted Chat.

Binoculars can somewhat compensate for back-lighting that causes my camera to produce monochromatic silhouettes. With binoculars it is possible to piece together momentary glimpses of a bird as moves through the branches. On the other hand, photos sometimes reveal details missed in the real-time sighting. More than once, I found a “new” species after I looked at the photos back home. That is what happened when I took the above photo of the chat. I heard a strange call in the dense shrubbery, but all I saw was a Prairie Warbler. Only after I got home did I find that one of my shots of a partially obscured yellow blob actually revealed the chat. (Click on photos for more details and additional views).

My first “real” sightings are seared into memory. As a kid, I did not need binoculars to witness the courtship of a pair of Rose-breasted Grosbeaks. From the seclusion of a thicket, I watched the male display on the ground in an open area, singing all the while. And so on– my first Common Redpolls, Red-headed Woodpeckers, Peregrine Falcons (”Duck Hawks”)… Now, I have a second chance to experience the thrill of “discovering” an old friend, and a few of my new species have been simultaneous additions to both the sightings and the photo lists.

My most recent new “Life Bird Photographed” was this Yellow-throated Vireo, seen only a few days ago.

New additions to the list usually reflect my travels to more distant places. Among other recent entries were a Rufous-crowned Sparrow, seen last November in the Albuquerque’s eastern foothills…

…and on the same day nearby, a Black-throated Sparrow.

A spring visit to Alaska in 2011 added 16 newly photographed birds, but only one was also a true “lifer,” this Red-faced Cormorant on Katchimak Bay.

I had seen Pelagic Cormorants before, but this one was special because it provided my first image of this species.

Pigeon Guillemots seemed to be engaged in friendly banter on Gull Island in Katchimak Bay.

Though I had seen both common puffin species previously, I was able to get my first photos of a Tufted Puffin on Gull Island.

A Horned Puffin splattered across the bow of our sightseeing boat on Resurrection Bay, out of Seward.

This pair of courting Mew Gulls in Denali National Park, shot through the side window of a bus, was one of my favorite new additions to the list.

One of the earliest entries on my life list of photographed birds antedates my first DSLR. It is a “two-for” taken from behind the window of our former home in New Mexico with a 2 megapixel point-and-shoot through my Kowa scope– a Pinyon Jay and a Western Scrub-Jay.

Visit ROSYFINCH RAMBLINGS

Posted by: Ken @ 3:51 pm

Having been born in the depths of the Great Depression, I acquired some habits of speech that are difficult to shed. I call the refrigerator an “ice box,” and the basement is the “cellar.” Our grandchildren enjoy correcting (ridiculing?) my speech. In my childhood, we made family excursions to visit the summer homes of friends and relatives on the New Jersey shore. Back then, I fed bread scraps to generic “seagulls” and chased generic “sandpipers” along the surf line.

When she was only three years old, our granddaughter spotted a bird flying over just as we were posing for a family photo at Disney World in Orlando. “Seagull,” I casually stated. “No, Grandpa, it’s a gull. there is no such thing as a seagull.” Proud to say, I taught her well, but still fail to practice what I teach. (Can you spot the two birdwatchers in the photo?)

Granted, she had been pointing out and identifying birds from a very early age, and like a sponge, soaked up the birds’ proper names. Here she is, not quite two years old, correctly pointing out a House Sparrow.

Although I started keeping track of the birds quite early, my skills were initially limited to 20 or 30 of the common land birds in Chester A. Reed’s little pocket Bird Guide: Land Birds East of the Rockies (Doubleday, Page & Company, 1923).

The Guide did not include gulls and sandpipers. To me, it was as if they did not exist. When I graduated to a first edition Peterson Field Guide to the Birds, the small gray-scale illustrations of sandpipers and my inland residence contributed to my lifelong weakness in identifying these species.

“Sandpiper” meant those little robotic things that chased the foam from the breakers up onto the dry sand, and quickly reversed course to follow the foam back into the sea. At first I thought that sandpipers had eternally wet feet. Eventually I learned that this does not hold true all the time, and that some species are quite comfortable away from water for much of their lives.

Least Sandpipers, with their warm brown plumage and yellow feet, tend to favor the muddy edges of ponds.

The similar Semipalmated Sandpiper (with a much larger Yellowlegs in the background) has black legs and a gray back, and spends more time in deeper water.

The elongated shape of the Yellowlegs in the above photo suggests it is a Greater rather than the Lesser species, but the length and shape of its bill is a factor in identification. Here is a Greater Yellowlegs.

This is most likely an immature Lesser Yellowlegs, a bit smaller with a short, straight bill.

During a spring visit to Denali National Park I saw Greater and Lesser Yellowlegs, as well as Solitary, Spotted and Least Sandpipers on their breeding grounds on the tundra, quite removed from large bodies of water. Some perched in bushes, calling and singing like robins and sparrows. (Unfortunately, I had not yet taken up photography).

Around our condo in NE Illinois, temporary pools created by rainwater have attracted Solitary Sandpipers. This one appeared the morning after a heavy downpour.

Spotted Sandpipers stay to breed on the condo property long after the “fluddles” dry up. I photographed this one near our driveway, along the road, from inside our auto.

This past week, following up on reports posted to the Kane County Audubon Society website, Mary Lou and I made visits to a sod farm in Kaneville, Illinois and viewed from a gravel road that runs alongside its eastern border. Along the bare earth where sod had most recently been removed, we saw scores of Killdeer and Horned Larks and up to six Buff-breasted Sandpipers. They are quite handsome birds. This one approached quite closely.

We also saw four American Golden-Plovers, which like the Buff-Breasted Sandpipers*, breed in the Arctic tundra and migrate to southern South America. In fall, the plover must fly to its wintering grounds in Patagonia, a round trip of about 25,000 miles, including 2,400 miles non-stop over open ocean, one of the longest known migratory routes. Both species must build large stores of fat at stopover areas during migration, and their body weight may increase by 30-50% in preparation for the long flights.

American Golden-Plovers are uncommon but regular visitors to NE Illinois. (Click on this link for a video and more views)

I captured a Killdeer, a Buff-breasted Sandpiper and a golden-plover all in the same frame.

*More about the Buff-breasted Sandpiper from Wikipedia:

T. subruficollis breeds in the open arctic tundra of North America and is a very long-distance migrant, spending the non-breeding season mainly in South America, especially Argentina.

It migrates mainly through central North America, and is uncommon on the coasts. It occurs as a regular wanderer to western Europe, and is not classed as rare in Great Britain or Ireland, where small flocks have occurred. Only the Pectoral Sandpiper is a more common American shorebird visitor to Europe.

This species nests on the ground, laying four eggs. The male has a display which includes raising the wings to display the white undersides, which is also given on migration, sometimes when no other Buff-breasted Sandpipers are present. Outside the breeding season, this bird is normally found on short-grass habitats such as airfields or golf-courses, rather than near water.

Posted by: Ken @ 6:15 am

We left hot and dry Illinois for hot, humid and rainy Florida a few weeks ago. Most days the weather and other obligations have kept us from getting out into the wetlands.

This sunrise was typical on most days, and the rain was not far behind.

Happily, there were a few clear days that permitted us to take our visiting granddaughters to our clubhouse pool or to explore the wonders of our lawn and garden. The girls had fun chasing after anoles and geckos in our back yard pineapple patch.

Clutching a poor captive lizard, our older granddaughter does not appreciate the irony of this situation as her eyes communicate her displeasure about the Peacock Bass that our next door neighbor just caught. He quickly obeyed her firm command and immediately returned it to the water.

The girls found this odd creature that was carrying what looked like the bodies of a bunch of dead insects on its back. I had no idea of what it was, except that its jaws looked like those of an ant lion. My guess was close. An Internet search revealed that it was the larval form of the related Green Lacewing http://www.freshfromflorida.com/pi/enpp/ento/entcirc/ent400.pdf . It collects the debris to hide it from its prey, mostly aphids, as well as from any enemies such as ants.

With the girls acting as spotters, our back patio has produced a few nice finds. This Tricolored Heron was its usual busy self, dashing here and there in search of prey.

This plunge into the lake yielded hardly an appetizer.

An Anhinga dried its wings next to the lake.

A Great Blue Heron did not fit into the viewfinder.

A neighbor’s rooftop hosted a White Ibis.

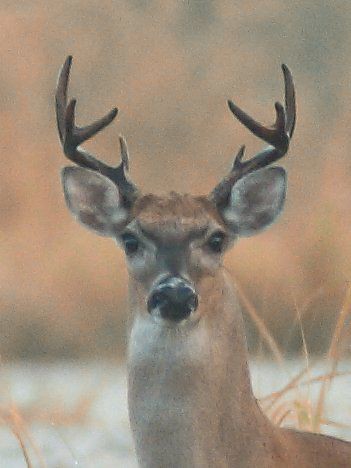

A couple of mornings we got out at sunrise, and were pleased to see a lone White-tailed deer. A bit smaller than those up north, they are not very numerous in the local wetlands. The young eight-point buck posed nicely. My monopod was not ready for this hand-held shot in the morning haze, so I processed it to make up for the blur.

An adult Bald Eagle flew overhead from its nesting territory towards the large lake in our subdivision.

At the heron rookery, this Yellow-crowned Night-Heron chick represented the third breeding cycle of the season. In all, over a dozen broods were successfully raised this year.

An older fledgling stood at an adjacent nest.

A female parent stood watch nearby. Ready for the molt, her feathers show wear and tear at the end of the nesting season.

Green Herons were also quite successful, raising broods in at least four separate nests. This immature bird has a streaked breast and shows a few tufts of natal down.

Posted by: Ken @ 2:11 pm

With good reason, Alaska usually comes to mind at any mention of Bald Eagles. Yet, it surprises some people to learn that, in the lower 48 states, breeding Bald Eagles are most numerous in Florida and Minnesota. In 1990 there were 535 breeding pairs in Florida, and 437 in Minnesota. The number of Florida breeding pairs rebounded rapidly to 1,102 pairs in 2001, then plateaued at 1,133 in 2005. In the meantime, Minnesota’s population climbed slowly at first, to 681 pairs in 2001, then shot up to 1,312 pairs in 2005, surpassing the Florida population.

This US Fish and Wildlife Service graph illustrates the recovery of breeding Bald Eagles in the lower 48 states since DDT was banned in the early 1970s:

In an earlier post, I described why the numbers of Bald Eagles in the more northern of the lower 48 states increase during summer and early autumn, due not only to newly fledged eaglets, but to the influx of more southern eagles. The Florida birds perform an interesting “reverse” northward migration after the breeding season. It is hypothesized that this contrary behavior is caused by another sort of “migration,” namely the vertical movement of the eagles’ main food source.

As Florida’s lakes heat up, the fish seek cooler temperatures in deeper water. Radio tagging of Florida eagles has shown that many follow the cooler water into the northeastern coastal states. Chesapeake Bay is a popular summer and fall gathering place for the Florida population.Immature birds tend to wander more widely than adults, with some even ending up in Canada. Conversely, North America’s northernmost Bald Eagles move south with the approach of winter, seeking open water as the larger lakes freeze up.

Alaskan eagles are, on average, heavier than those in Florida and have longer wings. I photographed this one in Soldotna, Alaska, along the Kenai River:

We have a particular interest in Bald Eagles, as we have been involved in protecting a recently discovered nest in our south Florida neighborhood. During the first week of October, 2011, Mary Lou and I were pleased to see that both members of the pair had returned to the nest:

They were already rearranging the nest materials:

On October 12, 2011, I photographed one of the pair at sunrise, flying from the nest area in the general direction of the largest lake in our subdivision:

On October 16, 2011, the female was sitting high on the nest…

…while her mate (judging by its slimmer build and slightly smaller size) roosted in a nearby Australian Pine:

We first became aware of the local pair of eagles on December 4, 2007, when I photographed them mating on the rooftop of a house just across the lake from our home:

As there had not been a record of an active Bald Eagle nest in Broward County since several years before DDT was abolished in the early 1970s, I reported the sighting on the Tropical Audubon Society’s Web page, and birders in neighboring Pembroke Pines had a general idea of where they might be breeding. In March, 2008, Kelly Smith, a local middle school teacher found the nest, located only about 150 feet from a busy boulevard. It contained one nearly full-grown eaglet.

This photo of “P. Piney One” was taken by Kelly Smith on March 15, 2008 and is reproduced here with her permission:

This pair of eagles has returned to the same nest each year, successfully raising and fledging two chicks in 2009, three in 2010, and two more this past spring. The nest is about 50 feet high in an exotic Australian Pine tree with smaller trees blocking most of the view, so we only get distant looks.

On December 11, 2008, both adults are shown sitting on the nest, only two days before the first of two eggs was laid::

Local middle school students conducted a nationwide poll that chose names for the two eaglets, “Hope” and “Justice:” They hatched on January 15,2009. Here they are, squabbling with each other at exactly one month of age. Hope, the older and larger, is on the left:

The eagle nest attracted a great deal of attention, and crowds of up to 100 people came to see the antics of the eaglets, causing traffic hazards as they stopped on the roadway and parked illegally.

The Mayor took an interest in the nest, which is located on City of Pembroke Pines property, and he announced his intention to declare the site a City Bald Eagle Sanctuary, and took measures to protect both the eagles and observers.The City has amended its planning documents to pave the way for an ordinance that will provide safeguards against disturbance of any eagle nest in the city. This past summer, major resurfacing of the roadway and construction of a sidewalk were suspended in the area of the nest during the eagles’ breeding season (May 15 - October 1).

I photographed these three eaglets on March 2, 2010. The Middle School students’ poll resulted in them being named Chance, Lucky and Courage. All three fledged successfully:

The eagles returned in October, 2010 to refurbish the nest, and eggs were laid around December 11. ( * See end note about how we estimate the time of egg laying and hatching). On January 23, 2011 at the age of about 9 days, this chick was first seen, peering over the nest rim:

Here, it waits as its parent tears off a bit of food. A younger sibling was not yet visible from the ground:

The Parent eagle feeds the chick :

This was about as good a view we could get from 150 feet. Vegetation now makes viewing much more difficult. Plans for a nest camera did not materialize:

Here is the older of the two eaglets, on February 3, 2011. Much of her natal down has already disappeared:

At one month old, on February 15, 2011, the down had been reduced to a fuzzy cap:

Less than two weeks later, on February 27, 2011, the eaglets looked almost as large as adults. We called them “P. Piney Seven & Eight.” Bald Eagles exhibit sexual dimorphism that starts when they are nestlings, with the females usually considerably larger than males. PP 7 is the larger and was presumed to be a female:

At two and a half months of age on March 23, 2011 they were exercising their wings, preparing for their first flight, which usually occurs when they are between 10 and 12 weeks old. PP7, on the right, has more white underneath than her younger brother:

On March 30, 2011, we found PP8 alone in the nest; PP7 had flown off, but returned within three days to be fed:

On March 30, PP8 was “helicoptering,” hovering in place up to a foot off the ground:

Here, on April 3, 2011, my last shot of PP7 shows her roosting in a tree next to the nest. PP8 was flying back and forth on branches in the nest tree:

*In estimating the timing of the laying of eggs and hatching of the eaglets, we must depend upon clues from changes in the behavior of the adults. The onset of incubation coincides with the laying of the first egg, which is when we suddenly see one of the pair down deep and immobile in the nest. Hatching is a time of excitement, as the parents shift position frequently, peer down into the nest, and they start bringing in prey and tearing off bits to feed the tiny chick. The adults also sit a bit higher in the nest after the first egg hatches, supporting themselves on their wings to form a “tent” to shelter the chick and yet provide warmth to any eggs that have not yet hatched.

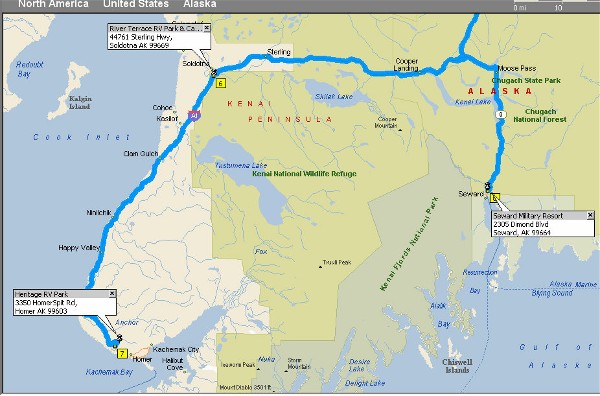

We enjoyed a scenic four hour drive from Homer to Seward, first retracing our route north and westward on Sterling Highway (Alaska #1). The early King Salmon run bypasses Soldotna for some reason, but upstream at Sterling, fishermen were lined shoulder-to-shoulder along the banks of the Kenai River. Joining Alaska #9 southward, we were treated to the rugged beauty of the Chugach Mountains. This is a continuation of the narrative of our Alaska journey, which begins at this link.

We stayed three nights at Seward Military Resort. That’s our 32 foot RV at the right end, with our older daughter’s 31 footer next to us:

The views around the Resort were superb:

After we arrived, sirens suddenly began to howl, and huge loudspeakers blasted out a tsunami warning! They said to get to high ground immediately, but all the road led downhill. The warning was repeated several times, then we received an all-clear with the explanation that it had been issued in error. There had been quite a large earthquake in the Aleutian chain that did cause some anxiety about the possible threat of a tsunami.

On our first full day in Seward, we took a dinner cruise to Fox Island in Resurrection Bay. Our trip coincided with the summer solstice, and the days were so long that it was difficult to keep track of the time. The sun did not set until after 11:00 PM, and rose a little after 4:00 AM. The sky remained bright and blue all night (In Denali, the days were 21 hours long).

Here is a view of the Seward harbor, taken after dinner, at about 10:15 PM. Note how few people are out on the docks:

Our granddaughters (in pink) worked very hard at completing all the tasks necessary to qualify as Junior Rangers by the end of the cruise. They kept track of the wildlife sightings, and took their duties very seriously, even picking up litter in the dining area.

Here they are administered their oath of office:

We were thrilled to see a Bald Eagle swoop down nearby and catch a fish. Here, it repositions its catch in its talons:

The next day we took a 6 hour wildlife cruise the full length of Resurrection Bay. The weather could not have been better.

A pair of Marbled Murrelets in breeding plumage hurried out of the way of our ship. They are black and white away from the breeding season:

The Marbled Murrelet (Brachyramphus marmoratus) is a small seabird from the North Pacific. It is a member of the auk family. It nests in old-growth forests or on the ground at higher latitudes where trees cannot grow. Its habit of nesting in trees was suspected but not documented until a tree-climber found a chick in 1974 making it one of the last North American bird species to have its nest described. The Marbled Murrelet has experienced declines in their numbers since humans began logging their nest trees beginning in the latter half of the 19th century. The decline of the Marbled Murrelet and its association with old-growth forests have made it a flagship species in the forest preservation movement. (Wikipedia)

The murrelets’ breeding colors provide camouflage in their treetop nests:

Common Murres appeared rather more brownish than I expected. Note the agae-rich water in this fjord. The long periods of sunlight cause algae to bloom in mid-summer:

A beautifully iridescent Pelagic Cormorant flew by:

We encountered a noisy herd of endangered Steller’s Sea Lions:

In the distance, Mountain Goats rested on the mountainside:

Glacous-winged Gulls nested in small groups on rocky ledges:

We saw many Black-legged Kittiwakes that were nesting in cliffs beside the bay:

A large kittiwake colony was at the far southern end of Resurrection Bay:

This Horned Puffin was the first one that either Mary Lou or I had ever seen:

Now I have seen all three North American puffin species. For me, it was ABA Life bird # 579. I captured it in flight, my favorite bird photo from the cruise:

We sighted another Red-faced Cormorant; its face does not show up very well, but its large head with two crests are characteristic of the species:

Sea Otters thrilled the children with close-up encounters:

Dall’s Porpoises frolicked in the open water at the mouth of Resurrection Bay. Note the white marking on their dorsal fins:

A Humpback Whale surfaced and blew a few times– I missed all the good shots:

Bear Glacier exhibits a central moraine, a line of rocks deposited where two glaciers came together:

Our granddaughters surprised us by remaining out on the deck for almost the entire cruise. Sporting their Junior Ranger badges earned on the dinner cruise the previous evening, they followed Ranger Jen all about, asking her questions and “interpreting” for the passengers. They had memorized the names of every creature that was displayed on a poster in the galley. Here they are trying to see how long they can keep their hands in a bucket of cold water just hauled up from the waters of the bay. They are learning of the importance of blubber as insulation. (Do I sound like proud Grampa?)

The seven year old is on the left in the green jacket, and the six-year old is in hot pink with the white hat. They are broadcasting their observations over the ship’s intercom:

Our two sons-in-law put in two full days of deep sea fishing. There’s a consensus– “We shall return!”: