It’s nice when the birds come to visit. During our eleven years of living in New Mexico I encouraged them with feeders, and attracted 120 species. Back then I set up my spotting scope inside the house and photographed the birds by focusing a little 2 megapixel point-and-shoot camera through the scope’s eyepiece. My New Mexico yard list and photos may be seen at this link.

Unfortunately, after moving to Florida I kept my “yard list” on my Palm handheld, and lost it when a computer crash coincided with my switch from the Palm to an incompatible iPod Touch. I think it was in the high 50s, but some day I will try to reconstruct it. Anticipating the question, I promised an answer when I posted “Why in [!!#!@*##&%] Did You Move From New Mexico To Florida?”

However, I never got around to explaining our motive for relocating from a mile and a half high in the mountains to a hot and muggy lakeside plot. I still plan to address this, but it is a story in itself, as is, indeed, our decision to occupy a second residence. Now that Mary Lou and I have homes in both Florida and Illinois, I have collected photos of quite a few yard birds that I have photographed, many from inside or from porch and patio.

Our condo home and “front yard,” in northeastern Illinois:

In Illinois, our “yard” includes about a city block of disturbed land that was fitted out with utilities and fire hydrants and then abandoned. It was to be packed with more townhouse style condominiums, but not long after we moved in about four years ago, our builder’s plans were terminated by the burst of the housing bubble. The area, formerly a cornfield, quickly reverted to a weedy grassland and now attracts breeding sparrows, Red-winged Blackbirds, Meadowlarks, Horned Larks, Killdeers and Spotted Sandpipers. Pipits and longspurs have visited during the winter, and migrating geese and Sandhill Cranes often stop by. Spring rains cause temporary puddles (local birders call them “floodles) where ducks sometimes visit. Raptors hunt for prey.

The builder erected wooden posts to mark the various utility lines. Waste broken slabs of concrete and rocks were left in piles along the road. Lacking any other elevated vantage points, birds like to rest on them. I can simply focus on one of them and, if patient, sometimes be rewarded with nice photos. Now it is almost time for us to return to Florida, and this is a retrospective look at a few of our Illinois yard birds.

Here an American Kestrel flies up for a landing on a post that marks the water line:

The kestrel eyes me suspiciously from my vantage point on the condo’s front steps:

By parking my car along the street near a rock pile I can wait to be surprised, as by this Song Sparrow:

This Savannah Sparrow chose to sing from a post that is painted red, to mark an electrical line:

I heard a Vesper Sparrow singing, and parked near where I last saw him:

A male American Goldfinch perched on a willow just across the street from our “yard.”:

Luckily, a Meadowlark approached with the sun almost behind it, and I was surprised at how the image turned out:

The Horned Larks have a nest near another pole that is only about 15 feet from the road in front of our home:

In the fall, American Pipits arrive in flocks, ignoring me in my automobile “blind:”

This year, three Sandhill Cranes made repeated visits, readily viewable from our front door:

Canada Geese congregate in the largest “fluddle,” which usually holds water all spring and summer long, finally drying out around September:

From inside my upstairs window, I captured this Snow Goose, the only one I have seen in our “yard:”

This Spotted Sandpiper, nesting nearby, habitually sang from this particular piece of roadside concrete rubble:

This month, after a brief thunderstorm, two Solitary Sandpipers turned up in one of the “fluddles:”

The sandpiper casts an imposing reflection on the fast-disappearing surface:

This molting adult Red-tailed Hawk is one of a pair that nested about a quarter mile away:

For the past three summers its noisy youngsters also perched on the inoperative street lights:

There is more beauty to be found among the grass and weeds. Pesky Queen Anne’s Lace hosts Black Swallowtail butterfly larvae:

A diminutive Eastern Blue-Tailed Butterfly stops to rest on a grassy leaf:

I’m not sure of the identity of this blue composite flower, but it grows wild and certainly is pretty. Is it Chicory, a flax?:

Travel, first to Alaska, and more recently in Europe, has occupied much of my past two months. Before leaving for a visit to Spain and a western Mediterranean cruise earlier this month, I wrote three blog posts and scheduled them for publication on consecutive Saturday mornings. I now have to catch up and tell about the varied results of my recent hunting experiences.

The great painter John James Audubon was known to cook and eat many of the birds he collected.

“Although he would shoot the birds for sport, he also shot them in order to paint their features. In his mission for new specimens, Audubon would shoot a minimum of a hundred birds each day. ” http://www.princetonaudubon.com/audubon-.htm

Audubon was known to be quite an epicure, and I remember reading his accounts of the varying flavors of different birds and mammals (including at least one rat). However, he was not an insensitive killer.

“Because he worked in the wilderness for long stretches with no other food source, he had to eat those birds, too. (He recounted one occasion when he drew a live hawk in his kitchen, and the bird’s eye ‘directed towards mine, appeared truly sorrowful.’ He released the creature as quickly as he could.)” http://www.strangescience.net/audubon.htm

Well, relax– I only hunt birds with binoculars, and more recently, a camera. Therefore I will not be discussing a recipe for blackbirds in a pie, but take a good look at this one.

The front view of this Bobolink only hints at its beauty.

Bobolinks on the prairie near our NE Illinois home have been a main target for me the past several summers. (Click on this image for more views):

I keep trying for the”perfect” shot of a male Bobolink in breeding plumage. It must be taken from a rear quarter, with the bird turning his head halfway, to show the contrast between his face and the nape of his neck. Then, the light must be just right to provide some eye shine against the dull black face. The bird must be near enough to permit definition of its feather patterns, and it must be in perfect plumage.

These elements have never yet been aligned in my many attempts for Bobolink “perfection.” Just before departing on our July Alaska trip I visited Nelson Lake/Dick Young Forest Preserve near our Illinois home.This time I saw up to 20 Bobolinks, mostly adult males. Those near the path always seemed to see me first and high-tailed it to distant pastures. Only two rested within camera range. Although in plain view, they were always at the outer limits of my camera’s resolution, and the images were soft when cropped. Some had scruffy plumage, like the one I photographed the previous day (See: Illinois prairie in early summer). My most common flaws have been failure to catch light in their eyes, and failure to get near enough for a crisp image.

I also keep trying to “bag” a singing Dicksissel at close range, such as this perfect specimen with a clear yellow breast:

Common Yellowthroats seemed to be everywhere, including this female, foraging for insects in the spent flower heads of Queen Anne’s Lace::

American Goldfinches are now breeding, their life cycle tuned to the ripening of the thistles that provide down for nests and food for nestlings:

It’s fun to try to catch a goldfinch in an interesting posture, but one must be very quick (and lucky):

Let’s depart momentarily from the “yellow bird” theme. I particularly enjoy chasing down the “Little Brown Jobs.” This year, though I have heard them singing in the grass, the rare Henslow’s Sparrows have eluded me. However a Field Sparrow kindly stepped up to represent the family:

In a lucky shot, I captured another Field Sparrow in flight, as it launched from its perch just as I depressed the shutter:

After the Henslow’s Sparrow, this year’s most elusive quarry has been the Sedge Wren. The prairie grass is now 5 or more feet high, and it is very difficult to shoot through the vegetation. Yesterday Mary Lou and I encountered two pairs of Sedge Wrens that appeared to be protecting a nest or fledglings close to the path. Nearly all my photos were partially obscured by greenery, and the first bird was back-lighted when it finally came out into the open. I used fill flash because of the very bright conditions and dark shadows. I had been trying all summer to get a clean shot of one of these prairie sprites, and this was my finest opportunity this year.

These are probably the best I could expect, but they capture the Sedge Wren’s reclusive nature:

A male Indigo Bunting graced us with his presence:

So far I have not been successful in obtaining the classic shot of a singing meadowlark on a big round fence post, and have to settle for one that dwarfs his skinny perch :

Or an earlier one, ready to hang on the wall with my other “trophies:”

We enjoyed a scenic four hour drive from Homer to Seward, first retracing our route north and westward on Sterling Highway (Alaska #1). The early King Salmon run bypasses Soldotna for some reason, but upstream at Sterling, fishermen were lined shoulder-to-shoulder along the banks of the Kenai River. Joining Alaska #9 southward, we were treated to the rugged beauty of the Chugach Mountains. This is a continuation of the narrative of our Alaska journey, which begins at this link.

We stayed three nights at Seward Military Resort. That’s our 32 foot RV at the right end, with our older daughter’s 31 footer next to us:

The views around the Resort were superb:

After we arrived, sirens suddenly began to howl, and huge loudspeakers blasted out a tsunami warning! They said to get to high ground immediately, but all the road led downhill. The warning was repeated several times, then we received an all-clear with the explanation that it had been issued in error. There had been quite a large earthquake in the Aleutian chain that did cause some anxiety about the possible threat of a tsunami.

On our first full day in Seward, we took a dinner cruise to Fox Island in Resurrection Bay. Our trip coincided with the summer solstice, and the days were so long that it was difficult to keep track of the time. The sun did not set until after 11:00 PM, and rose a little after 4:00 AM. The sky remained bright and blue all night (In Denali, the days were 21 hours long).

Here is a view of the Seward harbor, taken after dinner, at about 10:15 PM. Note how few people are out on the docks:

Our granddaughters (in pink) worked very hard at completing all the tasks necessary to qualify as Junior Rangers by the end of the cruise. They kept track of the wildlife sightings, and took their duties very seriously, even picking up litter in the dining area.

Here they are administered their oath of office:

We were thrilled to see a Bald Eagle swoop down nearby and catch a fish. Here, it repositions its catch in its talons:

The next day we took a 6 hour wildlife cruise the full length of Resurrection Bay. The weather could not have been better.

A pair of Marbled Murrelets in breeding plumage hurried out of the way of our ship. They are black and white away from the breeding season:

The Marbled Murrelet (Brachyramphus marmoratus) is a small seabird from the North Pacific. It is a member of the auk family. It nests in old-growth forests or on the ground at higher latitudes where trees cannot grow. Its habit of nesting in trees was suspected but not documented until a tree-climber found a chick in 1974 making it one of the last North American bird species to have its nest described. The Marbled Murrelet has experienced declines in their numbers since humans began logging their nest trees beginning in the latter half of the 19th century. The decline of the Marbled Murrelet and its association with old-growth forests have made it a flagship species in the forest preservation movement. (Wikipedia)

The murrelets’ breeding colors provide camouflage in their treetop nests:

Common Murres appeared rather more brownish than I expected. Note the agae-rich water in this fjord. The long periods of sunlight cause algae to bloom in mid-summer:

A beautifully iridescent Pelagic Cormorant flew by:

We encountered a noisy herd of endangered Steller’s Sea Lions:

In the distance, Mountain Goats rested on the mountainside:

Glacous-winged Gulls nested in small groups on rocky ledges:

We saw many Black-legged Kittiwakes that were nesting in cliffs beside the bay:

A large kittiwake colony was at the far southern end of Resurrection Bay:

This Horned Puffin was the first one that either Mary Lou or I had ever seen:

Now I have seen all three North American puffin species. For me, it was ABA Life bird # 579. I captured it in flight, my favorite bird photo from the cruise:

We sighted another Red-faced Cormorant; its face does not show up very well, but its large head with two crests are characteristic of the species:

Sea Otters thrilled the children with close-up encounters:

Dall’s Porpoises frolicked in the open water at the mouth of Resurrection Bay. Note the white marking on their dorsal fins:

A Humpback Whale surfaced and blew a few times– I missed all the good shots:

Bear Glacier exhibits a central moraine, a line of rocks deposited where two glaciers came together:

Our granddaughters surprised us by remaining out on the deck for almost the entire cruise. Sporting their Junior Ranger badges earned on the dinner cruise the previous evening, they followed Ranger Jen all about, asking her questions and “interpreting” for the passengers. They had memorized the names of every creature that was displayed on a poster in the galley. Here they are trying to see how long they can keep their hands in a bucket of cold water just hauled up from the waters of the bay. They are learning of the importance of blubber as insulation. (Do I sound like proud Grampa?)

The seven year old is on the left in the green jacket, and the six-year old is in hot pink with the white hat. They are broadcasting their observations over the ship’s intercom:

Our two sons-in-law put in two full days of deep sea fishing. There’s a consensus– “We shall return!”:

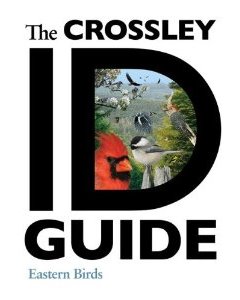

Review: The Crossley ID Guide: Eastern Birds

Richard Crossley

Princeton University Press

When I first picked up this book, I was surprised at how hefty it was. Like so many other birders, I saw the pre-publication press releases and the author’s video preview. The computer screen images of birds in multiple poses and at various distances were very appealing. I did not give much thought to the fact that displaying 640 of these plates in a readable format would require lots of large pages. Indeed, the book measures about 8 x 10 inches and its 544 high-quality heavy pages produce a volume that is 1 1/2 inches thick and feels like it weighs about 4 pounds. This is not a field guide, nor is it meant to grace the cocktail table. Rather, it is a unique tool for learning how to better identify the birds. It includes an unprecedented 10,000 individual bird images, all from Crossley’s own collection, except for a handful contributed by other photographers.

Crossley’s departure from the normal field guide format starts just inside the flexible front cover of the first page. A simplified display of its contents, two pages wide, depicts thumbnail-sized unlabeled photos of representative species, collected into two major groups: Waterbirds (Swimming, Flying and Walking) and Landbirds. The Landbirds are subdivided into Upland Gamebirds, Raptors, Miscellaneous Larger Landbirds, Aerial Landbirds, and Songbirds. This is followed by a 16 page “Quick Key,” a surprisingly useful table of contents that builds upon the same classification scheme. Each page of the Key includes 3 to 7 rows of proportionally sized color photos of all the more widely distributed species addressed in the book. Each photo is tagged simply with a four-letter “bander’s shorthand” species code and a page reference, an early clue that space will not be wasted on unnecessary narratives.

This is a book designed to be absorbed visually rather than to be read from cover to cover. The order of species is logical, user-friendly, and should appeal to birders at all levels of experience. Rapid advances in scientific understanding of the relationships between species often results in them being reordered; guides that adhere to a strict taxonomic classification can be outdated before they are published.

Resolving not to go directly to the plates (though I admit to a few early peeks), I started by reading the Introduction, twelve pages of dense text, interrupted by four color plates on bird topography. It is very informative, and provides suggestions on how to use the Guide, and “How to be a Better Birder.” The latter section contains much interesting and useful information about avian topography, molt and terminology. The topography plates are particularly well executed. Instead of the generalized illustrations so commonly seen in field guides, Crossley uses several large format color photos of birds from the various groups to better point out their unique plumage and anatomic features.

The text becomes more sparse and concise as we move into the major groups of illustrations. There are general notes about behavior traits that help locate and distinguish between species. For example, Crossley points out the importance of scrutinizing every member of a flock of geese, as they may act as “carriers” of less common species. In the case of flocks of shorebirds, their tendency to group together by species may call attention to a “loner” that may be particularly interesting. The section on raptors addresses issues of plumage variation peculiar to some species and related to age in all. Crossley suggests that variations in color among sandpipers might best be regarded as shades of gray– he advises us to learn to “think in black and white.”

Turning to the plates, they can be a bit overwhelming at first, but they follow a general pattern. Birds in the foreground are nearer and larger. Variations in appearance related to sex and age, as well as many “in between” plumages are pointed out here. In the background, the birds appear smaller and more distant. Labels are generally not needed beyond pointing out major features such as sex and subspecies differences, but minor variations between individuals related to age and stage of molt are often self-evident and do not require explanation.

In comparison to guides that have preceded this book, the Crossley ID Guide stands alone in depicting a much greater variety of appearances that may relate to such factors as postures of a bird, or the different positions of its wings in flight, as well as lighting, distance and sometimes its flocking and social behaviors. We see dense flocks of feeding Snow Geese, resting Sanderlings… birds doing what birds do: sleeping, preening, sunning… closely packed rafts of Common Murres and Greater Scaup… Upland Sandpipers dispersed singly in a short grass prairie… Cave Swallows swarming around their nests along a beam under overhanging eaves of an open livestock shelter.

Aside from the visual delight of the plates, Crossley’s captions are packed with identification tips that address not only size, shape and plumage, but also voice, behavior, and similar species.

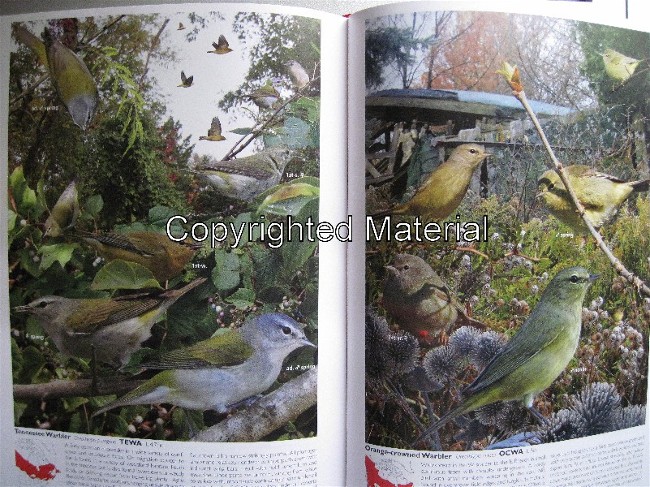

For example, facing plates of the Tennessee and Orange-crowned Warblers provide very useful comparisons between them. What birder has not had to deal with fleeting looks at one of these species? They share some similar and variable features.Their diagnostic undertail coverts are not always evident as they move rapidly through trees and shrubs. In addition to providing a large number of photos of both species in varied plumage, Crossley points out behavioral clues, such as the Tennessee Warbler’s tendency to occur in flocks and often hang upside-down in search of prey, in contrast to the more reclusive and often solitary Orange-crowned species, with its robust and longer-tailed appearance.

Because of their close taxonomic relationship, traditional guides also place the Tennessee and Orange-crowned Warblers next to each other. However, they may show only two or three examples of typical plumage forms for each. For the Tennessee Warbler, Crossley’ Guide displays eight views of perched and four more of flying birds, showing us four distinct plumages as well as typical postures. Six recognizable photos of the Orange-crowned species include variations of three different plumages.

On the other hand, less-experienced birders will welcome the fact that plates of the somewhat similar Blackpoll and Black-and-white Warblers occupy facing pages. Since these two species are not as closely related, other field guides that follow the conventional taxonomic order may separate them by two or more pages of other species. Conveniently, Pine and Bay-breasted Warblers, whose similar appearance may pose a challenge even to the most experienced birders, are located in the two pages just before that of the Blackpoll, with which either might be confused. In the text, plumage differences are analyzed in detail.

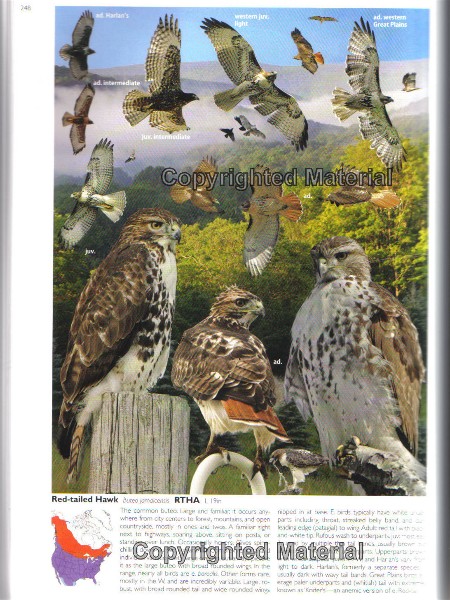

There are several species that exhibit a great deal of variation. The Red-tailed Hawk is one of them:

I compared Crossley Red-tail images and text with those in Sibley’s Guide to the Birds of Eastern North America. The former has 18 images of Red-tails, including flight shots of Harlan’s and western forms. The Crossley text has quite a detailed discussion of the various plumages. Sibley includes 33 images of this species over a two-page spread, including 5 of the dark morph, noting that it is very rare in the east, and 3 of the uncommon Harlan’s, morph. Arguably, Crossley falls a bit short in graphically illustrating the colors, but does better in showing this Buteo’s appearance in flight.

The Savannah Sparrow is another species that shows plumage variation in eastern populations. Crossley provides 10 images, 5 of which are in large enough format to see the birds’ lores. While the amount of yellow seen in the field may vary, it can be a useful feature in identification. None of these excellent images, in varied poses, show yellow lores, but their value in identification is mentioned in the text, along with is a detailed discussion of the plumage, especially the bird’s breast streaking. Sibley has images of 8 Savannah Sparrows, with the amount of yellow varying from none in the Ipswich to quite bright in one. The latter are accompanied by excellent plumage and behavioral descriptions. In both of these examples, Crossley provides large images and very pertinent habitat settings, not possible in the more sparse format of a field guide.

In a departure from the pattern of showing multiple views, an unaccompanied Black Rail lurks furtively in the darkness among the reeds. No open side-on photo, no flight shot– yet a view much better than even those birders lucky enough to have seen one might have wished for. This is the author’s own prized photo– suffice to say it is the only one of this species in his collection (or did he deliberately show this bird, alone and secluded?).

Then there are a few of those delightful and whimsical presentations, such as that of Least Terns swarming around a Cape May lifeboat pulled up on the shore. Comparing the Crossley ID Guide to any field guide is somewhat like comparing apples to oranges. One is not better than the others– the important point is that the book I am reviewing is different… unique, and deserving of a place beside any birder’s easy chair.

Richard Crossley maintains a website with his blog that provides updates and corrections (of which there were only a handful). As necessary, he also elaborates on the captions in the book. I will admit to one disappointment I initially felt after I opened this book. Having watched the promotional video and rejoiced in the brilliance of the screenshots of several plates, I found many of the paper versions of the plates to be quite somber. Sometimes I wished for more light or more detail – even wanted a few of the distant birds to be more clearly recognizable. Some birds were hard to find or partially hidden behind foliage. Wouldn’t this book look better on a computer screen?

This issue is addressed in Crossley’s Introduction: “Just as in real life, the harder you look, the more you will see.” Although an e-book edition would be splendid, I’m pleased to feel the heft of this volume and leaf through its contents. My eyes can scan back and forth between facing and adjacent pages, and down to the text below– and back to a plate to look for that elusive sprite hidden in the shadowy underbrush, “just as in real life.” Being out there sure beats squinting, scrolling and searching.