Posted by: Ken @ 2:31 pm

I can’t remember when I started “playing” the piano, but by the age of 5 or 6 I could perform many simple songs, provided they were on the white keys. Within a couple of years I taught myself to accompany the melodies with “um-pah” chords with my left hand. Hit the root note with my pinkie, and go up one octave with my index finger; add the third note above and the fourth below. Make “sad” chords by moving my thumb down one half note, switch the chords to fit the sound of the melody. All of this without knowing the names of chords, whether major, minor, sevenths, ninth, diminished, or augmented. Only much later in life did I learn something about music theory. The theory helped me understand the rules, and made it easier for me to apply their principles and advance in knowledge.

Likewise, I’ve been watching birds most of my life. I know many of their sounds and behaviors, but I never fit them into any kind of system or theory. Jon Young, in his little book What the Robin Knows: How Birds Reveal the Secrets of the Natural World (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt), has enriched my birding experience by providing such a framework. It’s not a rigid system or code, but it helps interpret the actions of birds.

We’ve all had days when birding was slow. The time of year is right, the habitat looks perfect, but the birds seem to have disappeared. We might hear a familiar bird calling or singing here or there, but none are in view. We turn to watching butterflies and dragonflies, or simply end up saying it wasn’t a “birdy” day and return home disappointed.

An endorsement on the dust cover of Young’s book states “…[A]fter reading his marvelous book…[y]ou’ll discover a universal bird language that will speak to you whenever you go outdoors.”

Don’t you ever wish you could understand the language of birds? I’ve talked to the birds, and they’ve talked back to me and then to each other (Much ado about a squeak). Once, their excited scolding helped me trace the movements of a Bobcat as it circled around behind my back in the wetlands, and their silence has alerted me to the presence of predators overhead.

My iPod has an app which can translate speech into any of several selected languages. Since I have Cuban in-laws with extended families, I have used it to communicate with some of the non-English speaking relatives. Sometimes what comes out bears little resemblance to the intent of our words. We end up laughing into the speakers. Laughter, facial expression and other non-verbal clues often reveal more than our words.

This book won’t provide a literal translation of the robin’s calls and songs. It goes beyond the individual sounds, and provides them in a behavioral context. Much attention is devoted to the “body language” of birds when they are subjected to various types of disturbance. Their responses are described in three dimensions (and in a fourth dimension, time), supplemented by instructive diagrams. Young calls them the twelve “alarm shapes.”

What were these Gray Catbirds saying to each other? Are they fighting, or are they courting? Actually, their calls did not sound angry, and their pursuit seemed gentle, so I assume it was the latter.

These two Northern Mockingbirds were issuing more hostile calls.

This pair appeared to be squabbling over their property lines.

The mockingbird on the left was unwilling to give ground, and the hostility escalated, evidenced by their body language and slurred calls.

They finally came to blows. If my iPod were able to translate their “words,” there would probably be many bleeps in my transcript of this confrontation. The bird to the right flew off. My guess is that it was the intruder.

Birds cannot smile or grimace. The bony ridge over the eyes of eagles produces a perpetual frown. The male Bald Eagle, on the right, was acting amorous. Was he whispering “sweet nothings” into his mate’s ear?

He is startled when she rebuffs him severely.

Now they are obviously not on speaking terms.

Wild creatures don’t waste precious energy, so their actions are usually purposeful. What were these Black-legged Kittiwakes trying to accomplish with their raucous clamoring?

The first few chapters of What the Robin Knows classify and describe five basic types of bird vocalizations. Young calls the first four “baseline:” songs, companion calls, territorial aggression, and adolescent begging. These are the sounds associated with the birds’ normal activities. Disturbances and threats that upset this state of equilibrium stimulate birds to issue various types of alarm calls, the fifth category.

The text of the book provides examples of calls and songs by referring the reader to a collection of audio files at the author’s website, BirdLanguage.com. At first I found it a bit cumbersome to interrupt my reading to access the desktop computer. I tried listening with the browser on my iPod, but the files were in an incompatible format, possibly Adobe Flash. I even put off reading the book until I could use my netbook which I had left back in Illinois. Ultimately I found it easiest just to listen the the entire set of sounds in one sitting. Many were already familiar, but the experience helped me to understand their classification in the author’s scheme. Doing it this way also demonstrated some inter-species similarities between the various types of calls. Contact calls generally sounded soft and peaceful, while alarm calls were emphatic and energetic.

In late summer I took my usual morning walk in the wetlands next to our south Florida home. Although the sun was just rising, I was not greeted with a chorus of bird song. A couple of Eastern Towhees could be heard singing their “tip-tip-tee-tee-tee-tee-tee” song. A Common Ground-Dove produced an intermittent coo-like low whistle, a few mockingbirds sang halfheartedly, and a Carolina Wren burst into song and then fell strangely silent. Common Grackles fed their begging offspring. It was a perfect morning to pay attention to the birds’ baseline sounds.

Back in Illinois in the fall for warbler migration, I birded my favorite patches and had the familiar experience of having some great days with lots of sightings and other days when I was greeted by an eerie silence. But, thanks to this book, I made a special point of listening to the silence. Baseline sounds that I previously ignored took on new importance. I recognized the little two-note begging calls of fledgling goldfinches, the soft “seep!” contact calls of robins, and the quiet “chips” of a pair of cardinals.

While sitting in our daughter’s back yard I saw a good example of one such “shape.” I was watching chickadees, Mourning Doves and House Finches at and around her feeder. Suddenly the birds on the ground flew up into the trees. Some selected perches nearby, but all perched at least 5 feet off the ground. I knew that this was not the “shape” of an alarm triggered by a bird-seeking raptor such as an accipiter or falcon. At first I did not see the threat, but in a minute or so a neighbor’s dog ambled along their back fence line.

I think back to the time when I was photographing a Savannah Sparrow in the same back yard. It was exposed out in the open on a fence rail. Suddenly the bird looked up and froze in place. I also glanced up to see a Red-tailed Hawk moving along at rather high altitude. The sparrow appeared to recognize that the hawk posed no immediate threat, but took the precaution of stopping all motion so as not to attract undue attention. Contrast this to the time when a Sharp-shinned Hawk suddenly swooped into the yard, and the birds dove for the nearest cover.

Jon Young draws upon not only his years of experience learning and teaching the language of birds, but also that of others, including professional trackers and indigenous elders, dwellers of bush and jungle. When you read this book, I suggest that you get out in the field after reading each chapter and allow what you have learned to enrich your birding experience.

Review: How to Be a Better Birder

by Derek Lovitch

Princeton University Press

208 pages, 53 color illustrations, 10 maps

Look inside on Amazon.com

It’s easy to judge a book by its title. This one is “How to Be a Better Birder.” Not how to “Become,” but how to “Be.” Me, I’m always “becoming,” but I must admit that I have not yet arrived. I’d be too embarrassed to tell you my worst stories, but here are a couple that are not near as bad as those.

Before leading a Saturday morning bird walk at Rio Grande Nature Center in Albuquerque, I scouted out the area adjacent to the starting point. In a Cottonwood conveniently situated near the entrance trail I found a Greater Roadrunner moving about high in the branches, probably searching for a meal of hummingbird eggs or Mourning Dove nestlings. About 15 minutes later, as I led my charges along the path, I casually looked up at a brown blob moving between the green leaves and began to expound on the interesting behavior of the roadrunner. Well, one of the young participants pointed out that I was looking at a squirrel!

The first chapter of Lovitch’s book is subtitled “The ‘Whole Bird and More’ Approach.” Ho hum– Oh yes, I’ve heard this so many times, but what’s that about “More?” Maybe my approach requires fine tuning.

While walking a trail in the wetlands near my new home in south Florida, I spotted a bird soaring quite high in the sky. Easy call. Flying Bird → Hawk → Buteo → red tail → ? Duh, stop here, take its picture and move on to the next bird.

If I had applied some of the “More” that is packed into this compact handbook I would have noted that, in addition to its somewhat smaller size, this hawk presented a more graceful silhouette, and shorter pointed wings with comma-shaped light areas just inside their black tips. It wheeled in tighter circles, lacked dark patagial marks and had no belly band. The red in its tail was caused by diffusion of sunlight from above, not the red pigment of a Red-tailed Hawk. It was the first light morph Short-tailed Hawk I had ever seen, and I did not identify it until I looked at my photos on the computer screen back home.

I found the first chapter so interesting that I just had to try out some of Lovitch’s advice. Especially interested in the sparrow clan, the author provides two facing pages that illustrate the profiles of each genus. Everybody knows that Song Sparrows (Melospiza) are shaped differently than Chipping Sparrows (Spizella) and Swamp Sparrows (Passerculus). Yet we are encouraged to go beyond “general shape and size” and analyze the subtleties of size and shape of head, bill, tail, chest and belly. Don’t be fooled by some markings, such as chest spots. Lovitch provides an interesting artistic interpretation of plumage details:

“A Song Sparrow is an oil painting… Lincoln’s… is akin to a pen-and-ink drawing, while the washed-out, blurry streaking and more subtle contrasts of the Swamp Sparrow are like a watercolor.”

I set out into the field and found my Oil Painting…

…a Pen-and-ink Drawing…

…and a Washed-out Watercolor.

Lovitch cautions us not to rely on the infamous breast-spot to identify a bird as a Song Sparrow. All three of the above sport one, as does this Vesper Sparrow…

…and of course, the Savannah Sparrow.

I have misidentified all of the above sparrows in the past, and probably will continue to do so, but perhaps with less frequency. It was time to move on to the next chapter, “Birding by Habitat.”

Sure, we all know not to look for Sage Sparrows in a swamp, but Lovitch goes beyond the basics and challenges us to learn more about vegetation types and micro-habitats. Know the plants and you will know which birds are looking for food and shelter there. My aging brain simply does not retain all the names of the various grasses, shrubs and trees (and this is also true for butterflies, dragonflies and other insects, not to mention the last ten people who were introduced to me at a party), but it is nice renewing my acquaintance with the same ones over and over again!

The book addresses the importance of geography in the movement of migrating birds and predicting where they may concentrate in various seasons and weather conditions. Lovitch explains the importance of weather-related “overshoots.” On a macro scale, migrants may end up far out of their normal range because of such factors as faulty navigation, hurricanes or weather systems. Locally, overshoots occur most often over water, when migrating land birds must reverse course to seek the safety of the shoreline.

I found the chapter on “Birding by Night” to be captivating, as I read it when spring migration was at a peak. This is not only about listening to chirps in the night and watching the moon. It contains detailed instructions for constructing your own personal radar display to capture and interpret images from the previous night.

“Birding With a Purpose” emphasizes the importance of contributing to the greater fund of birding knowledge, whether through individual record-keeping and reporting on e-Bird and RBAs, participating in organized counts, census and banding activities, or even seeking volunteer opportunities or employment in scientific research endeavors. As is the case in earlier chapters, the book provides a wealth of pertinent references.

After a discussion of vagrants, Lovitch presents “A New Jersey Case Study,” which details the successes and failures of his birding trip to Cape May. He applies some of the concepts set out in his book, particularly relating to the ability to predict where the birds might show up under sometimes challenging weather conditions.

Finally, he extolls the benefits and joys of patch birding, or more properly, “Patch Listing,” strengthening my resolve to be more of a lister. It is so easy to neglect the value of properly recording the arrival, ebb and flow of species in a familiar spot. I resolve to improve in this aspect of my “Becoming” a better birder, even though I may never “Be” one.

Disclaimer: Princeton University Press supplied me with a review copy of this book.

Shared on Birding is Fun, July 3, 2012

Posted by: Ken @ 9:54 am

Book Review: Birding Hotspots of Central New Mexico.

Judy Liddell & Barbara Hussey

W.L. Moody, Jr. Natural History Series

Texas A&M University Press

Many birders are familiar with Judy Liddell’s popular blog, It’s a Bird Thing. Judy’s blog entries often describe her local trips with the Thursday Birders, a dedicated group of Central New Mexico Audubon Society members who get out to interesting places every Thursday morning. The current schedule of Thursday Birder and other CNMAS field trips may be found at this link.

Most of the Thursday Birder excursions are in or around the city of Albuquerque for a half day, making it easy to fit them into a busy schedule. Reading her narratives brings me back to the eleven years I lived in New Mexico. (Please don’t ask why I ever moved to Florida!)

Here are a few birds I photographed in my back yard, located on the east side of the Sandia Mountains just outside Albuquerque. I put a little 2 megapixel point-and-shoot camera up to my spotting scope and shot through the glass of our living room. The quality of these early images may be poor, but the memories they elicit are vivid!

Williamson’s Sapsucker

Cassin’s Finch

Pinyon Jay

Blue Grosbeak

Judy is active in Central New Mexico Audubon Society. In addition to leading CNMAS bird walks, she serves as Vice President and Program Chair. She also is Secretary of New Mexico Audubon Council and is a bird monitor for the Rio Grande Nature Center.

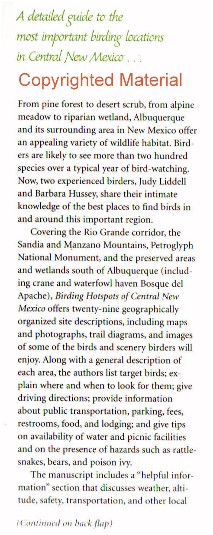

With fellow birder and experienced birding guide Barbara Hussey, Judy has co-authored Birding Hotspots of Central New Mexico. In addition to long and dedicated service for the Rio Grande Nature Center, Barbara is a former President and Board member of CNMAS, and one of the founders of New Mexico Volunteers for the Outdoors.

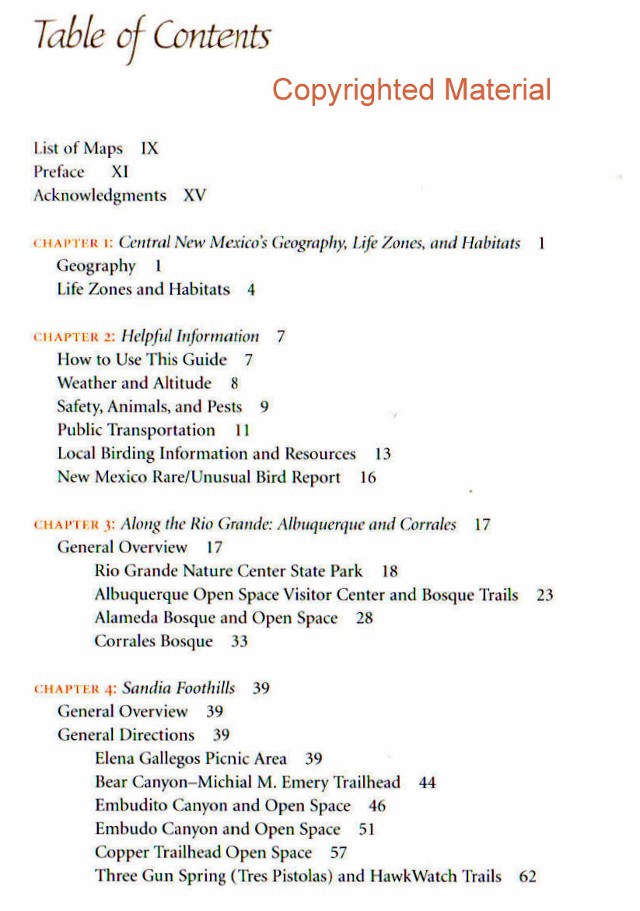

This new site guide draws upon the authors’ familiarity with six clusters of the 29 very best birding locations within easy driving distance from downtown Albuquerque. Sample page views:

Each of the concise site descriptions stands alone, thus avoiding cross-references and conveying a marvelous sense of place. This assures most efficient use of the visitor’s time– by suggesting the best way to follow a trail, providing locations of the nearest rest rooms, drinking water, lodging and gas stations, and even spots for a picnic lunch. An annotated checklist links species to the best places to see them, and there are many colored photographs that enhance the descriptions of each hotspot.

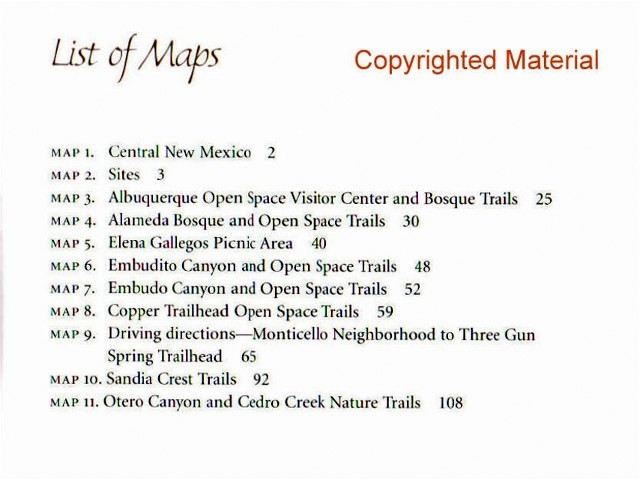

Eleven detailed maps are provided

Road and trail conditions and elevation changes are carefully noted, as are hours of operation, any entrance fees and proximity of public transportation if available. Particular hazards are pointed out as may be necessary, as well as wheelchair accessibility and obstacles for those with limited mobility. At some sites, the visitor will know what time of day is most favorable for birding, and where to get the best views when the trees are bare or fields are flooded. Nearly a dozen maps complement site-specific driving directions that all start from the intersection of I-40 and I-25 in the heart of Albuquerque.

There is a strong emphasis on how to most efficiently locate target species, some of which may be found almost exclusively at one or a few of the hot spots. All of the expected species are listed in an annotated checklist that references only the best locations for finding them.

Unlike some bird finding guides, the text is not cluttered with aging reports of rare and unusual birds. Instead, the reader is sensibly advised to consult the latest eBird and rare bird alerts before setting out. Nearly all of these locations are already indexed by name in eBird.

The flaps of the sturdy softback cover can be conveniently used as bookmarks. They contain more information about the the book and its authors:

Whether planning an extended trip or a few hours’ escape from a business meeting, birders with all levels of experience will find Birding Hotspots of Central New Mexico an invaluable traveling companion.

Avian Architecture: How Birds Design, Engineer, and Build

by Peter Goodfellow

Princeton University Press, 2011

What started my fascination with birds? When I delve deeply into the recesses of my memory, I find no sudden epiphany. I recall looking out the back window of our second story apartment on to the flat roof of the dry cleaner’s store, where a nighthawk was sitting on its eggs. My father had discovered it and pointed it out to me. It was interesting to see that the eggs were laid directly on the roof pebbles, without any semblance of a nest. A few days later, the eggs suddenly disappeared. In their place, unbelievably well-camouflaged, were two chicks. Knowing the date we moved away, I was no older than four years. It sticks in my memory, but did it light a flame?

Perhaps a year or so later, when visiting my uncle in a seminary in Ossining, New York, I came across a compact little nest, low in a hedge. Its lining consisted almost entirely of horsehair, and contained tiny spotted white eggs– three, I think. Two small brown birds scolded anxiously as I peered down into the nest. On a subsequent visit I found the nest to be empty, but in perfect shape. I carefully removed it from its attachments to the twigs and put it up behind the rear seat of the family’s 1937 Ford sedan, oblivious to the prohibitions of the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918. It was a work of art and a treasured possession. Over time, much of the straw fell away, but a perfectly pressed cup of horsehair remained.

Later, I learned that the tiny brown birds that wove the beautiful little horsehair nest were Chipping Sparrows. The criminal nature of my act was exposed when I displayed the nest at a Cub Scout meeting. In the meantime there had been other discoveries– Barn Swallows and robins gathering mud in puddles along the road, a Blue Jay whose entire nesting cycle unfolded in a tree only a few feet from an upstairs window…

…the unforgettable fire in the piercing yellow eyes of a Brown Thrasher whose nestlings I dared approach (Kane County, Illinois, May 28, 2010):

Nest structure ranges from the simple to the sublime–

American Oystercatcher nest (Brigantine, New Jersey, May 11, 2007):

Killdeer nest (Batavia, Illinois, May 12, 2009):

Bald Eagles on nest (Pembroke Pines, Florida, October 5, 2011):

Baltimore Oriole male inspecting his mate’s weaving of the foundation for their nest– or is he doing it himself? (May 9, 2011, Kane County Illinois):

As interesting and varied as bird nests may be, they only provide hints about their creators. A Mourning Dove nest can be so flimsy that the eggs may be visible from underneath. Yet, I once watched as a male Mourning Dove collected short lengths of twigs and brought them up to the female who was constructing her nest in a Cottonwood. She inspected each offering, turning the stick in her bill. Almost half the time, she discarded the gift and it fell to the ground. Her critical eye should have resulted in a durable masterpiece of avian architecture, yet a week later, after a rain storm, the nest was gone.

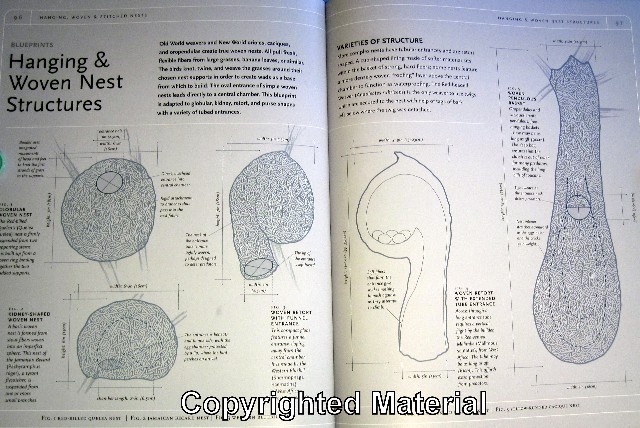

Goodfellow’s Avian Architecture is not only about structural diagrams and blueprints, though it goes into great detail in chapters about nine general types of nest construction, from simple scrapes, holes, platforms, cups, mounds and domes to intricately hanging and woven ones. There are also chapters on aquatic and mud nests, colonial and group nests, as well as intriguing descriptions of courts and bowers, and even edible nests and food stores.

Here is Goodfellow’s set of “blueprints” that introduce the chapter on woven nests, illustrating a variety of styles:

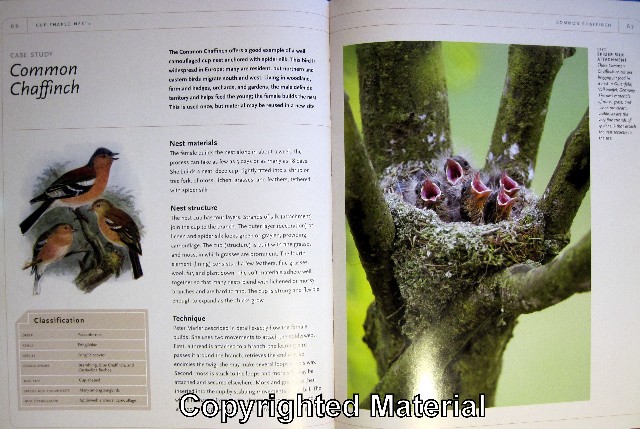

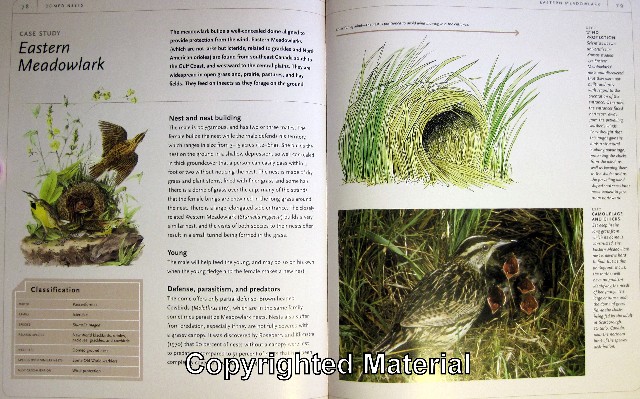

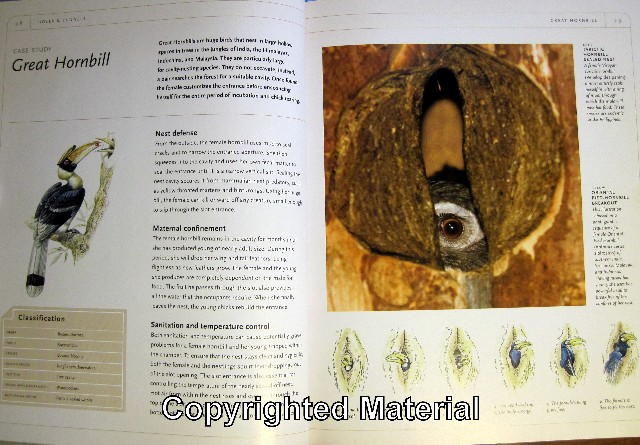

Each chapter discusses construction materials, but most of the book is devoted to case studies of individual species. The representative case studies address where and how the birds construct their nests and the unique features of each. Behavioral traits, breeding biology, habitat and conservation issues are detailed. Global in scope, the book provided me with much new and interesting information about unfamiliar birds.

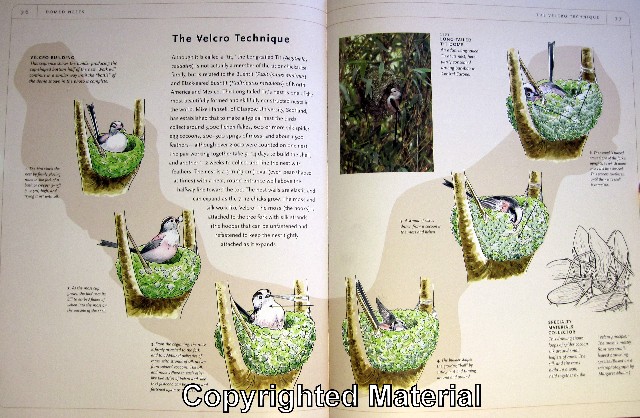

I did not know that birds actually invented “Velcro.” The same system of hooks and loops is used by several species to attach their nests or hold them together. The Long-tailed Tit builds its domed nest by creating loops of silk unwound from spider cocoons and fastening them to sprigs of moss. The selected moss leaves are just the right size to interlock with the silken loops. The attachments can be disengaged and repositioned to accommodate the growth of nestlings.

In each chapter, for a representative species, the author provides a very detailed and illustrated example of the steps involved in construction of the particular nest type, from beginning to end. Whether the bird is unfamiliar or one that is commonly encountered, these contain many interesting facts.

In the chapter on domed nests, the Long-tailed Tit’s construction methods are presented sequentially:

The Sooty-capped Hermit and the Common Chaffinch also use a similar technique. Two page case studies of selected species reveal many other interesting facts:

I learned that one of the largest nests of any bird species is that of the Social Weaver– a “condominium” that begins with a platform roof and includes up to a hundred separate compartments, individually built and occupied all year long. All residents share responsibility for maintaining the roof.

Nests are generally constructed from locally available materials, so they reflect adaptation to a wide range of habitats. The flamingo creates a trough around the perimeter of its nest site as it removes mud for its construction, while the Black Wheatear must utilize stones gathered from the high and treeless rocky slopes of the Atlas Mountains of Spain. It carries the stones, one at a time, to its nest site. Amazingly, we learn that this 1 1/3 ounce bird is somehow capable of moving rocks weighing as much as 10 ounces. Another example of the use of rocks in nest construction is that of the Horned Coot, which creates its own artificial island by piling stones into a cone up to 13 feet wide and three feet high.

The Eastern Meadowlark weaves fresh grass stems into the structure of the domed roof of its nest:

:

I have seen Northern Goshawks and Bald Eagles bring fresh green leaves to the nest. Other birds commonly incorporate greenery into nest construction. Whether it serves a function such as camouflage or pest deterrence, or is merely decorative is the object of speculation. I was a bit disappointed that the book’s index did not have an entry for green leaves or foliage, nor one on camouflage despite providing several pertinent examples in the text. Neither are there entries for vermin or mites, though the subject comes up a number of times.

The relatively brief index addresses mainly common and scientific species names. While this is a minor drawback, it somewhat limits the reader’s ability to search the text for some common elements in techniques and construction. . For example, when I wanted to find all references to the use of spider web or silk I found only three citations. One discusses the strength of this material in the section on hummingbirds’ nests, and the other two refer to its use by the Common Chaffinch. Yet, the book has other very pertinent descriptions of how birds use spider silk. For example, the Common Tailorbird utilizes spider and lepidopterus silk, as well as plant down, in attaching its rainproof nest under an arching leaf.

Also not indexed is a particularly intriguing method by which the Sooty-capped Hermit hangs its nest from a single “cable,” comprised of many strands of spider silk, which is attached to the edge of an overhead leaf. Since the nest could swing precariously and even tip over, this hummingbird adds a “tail” of spider silk cable beneath the nest and weighs it down with pellets of mud. The weighted tail serves as a counterbalance that keeps the nest from spilling out its contents.

Construction materials such a mud and silk are sometimes cross-referenced, but moss, hair, feathers, rocks or stones are not. However, the case studies provide interesting examples of specialized use of these components.

The female Tarictic Hornbill uses mud to seal herself into a brooding chamber for many months to lay eggs and rear young until they are completely fledged, depending upon the male to feed her and their offspring:

The final two chapters of Avian Architecture go beyond descriptions of the nest as a structure in which eggs are laid and young are reared. There are extensive and detailed case studies of courts and bowers, and the final chapter treats edible nests and food storage methods.

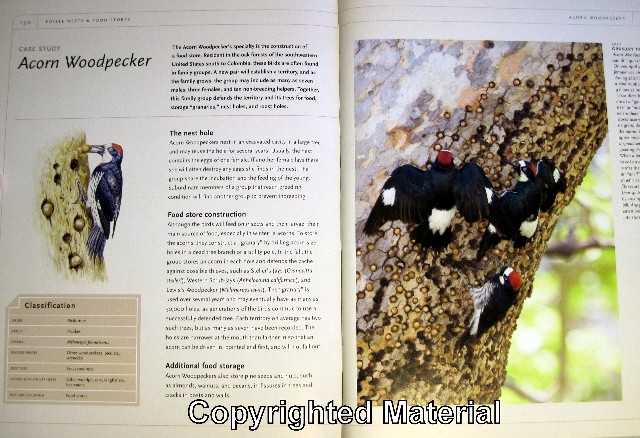

Studies of the Yellow-bellied Sapsucker’s technique for extracting sap and assuring its free flow, and the Acorn Woodpecker’s method of storing acorns and are especially interesting:

.

Avian Architecture is an entertaining and informative resource for anyone interested in the great diversity of bird nests, and the what, why and how of their construction.

Review: The Crossley ID Guide: Eastern Birds

Richard Crossley

Princeton University Press

When I first picked up this book, I was surprised at how hefty it was. Like so many other birders, I saw the pre-publication press releases and the author’s video preview. The computer screen images of birds in multiple poses and at various distances were very appealing. I did not give much thought to the fact that displaying 640 of these plates in a readable format would require lots of large pages. Indeed, the book measures about 8 x 10 inches and its 544 high-quality heavy pages produce a volume that is 1 1/2 inches thick and feels like it weighs about 4 pounds. This is not a field guide, nor is it meant to grace the cocktail table. Rather, it is a unique tool for learning how to better identify the birds. It includes an unprecedented 10,000 individual bird images, all from Crossley’s own collection, except for a handful contributed by other photographers.

Crossley’s departure from the normal field guide format starts just inside the flexible front cover of the first page. A simplified display of its contents, two pages wide, depicts thumbnail-sized unlabeled photos of representative species, collected into two major groups: Waterbirds (Swimming, Flying and Walking) and Landbirds. The Landbirds are subdivided into Upland Gamebirds, Raptors, Miscellaneous Larger Landbirds, Aerial Landbirds, and Songbirds. This is followed by a 16 page “Quick Key,” a surprisingly useful table of contents that builds upon the same classification scheme. Each page of the Key includes 3 to 7 rows of proportionally sized color photos of all the more widely distributed species addressed in the book. Each photo is tagged simply with a four-letter “bander’s shorthand” species code and a page reference, an early clue that space will not be wasted on unnecessary narratives.

This is a book designed to be absorbed visually rather than to be read from cover to cover. The order of species is logical, user-friendly, and should appeal to birders at all levels of experience. Rapid advances in scientific understanding of the relationships between species often results in them being reordered; guides that adhere to a strict taxonomic classification can be outdated before they are published.

Resolving not to go directly to the plates (though I admit to a few early peeks), I started by reading the Introduction, twelve pages of dense text, interrupted by four color plates on bird topography. It is very informative, and provides suggestions on how to use the Guide, and “How to be a Better Birder.” The latter section contains much interesting and useful information about avian topography, molt and terminology. The topography plates are particularly well executed. Instead of the generalized illustrations so commonly seen in field guides, Crossley uses several large format color photos of birds from the various groups to better point out their unique plumage and anatomic features.

The text becomes more sparse and concise as we move into the major groups of illustrations. There are general notes about behavior traits that help locate and distinguish between species. For example, Crossley points out the importance of scrutinizing every member of a flock of geese, as they may act as “carriers” of less common species. In the case of flocks of shorebirds, their tendency to group together by species may call attention to a “loner” that may be particularly interesting. The section on raptors addresses issues of plumage variation peculiar to some species and related to age in all. Crossley suggests that variations in color among sandpipers might best be regarded as shades of gray– he advises us to learn to “think in black and white.”

Turning to the plates, they can be a bit overwhelming at first, but they follow a general pattern. Birds in the foreground are nearer and larger. Variations in appearance related to sex and age, as well as many “in between” plumages are pointed out here. In the background, the birds appear smaller and more distant. Labels are generally not needed beyond pointing out major features such as sex and subspecies differences, but minor variations between individuals related to age and stage of molt are often self-evident and do not require explanation.

In comparison to guides that have preceded this book, the Crossley ID Guide stands alone in depicting a much greater variety of appearances that may relate to such factors as postures of a bird, or the different positions of its wings in flight, as well as lighting, distance and sometimes its flocking and social behaviors. We see dense flocks of feeding Snow Geese, resting Sanderlings… birds doing what birds do: sleeping, preening, sunning… closely packed rafts of Common Murres and Greater Scaup… Upland Sandpipers dispersed singly in a short grass prairie… Cave Swallows swarming around their nests along a beam under overhanging eaves of an open livestock shelter.

Aside from the visual delight of the plates, Crossley’s captions are packed with identification tips that address not only size, shape and plumage, but also voice, behavior, and similar species.

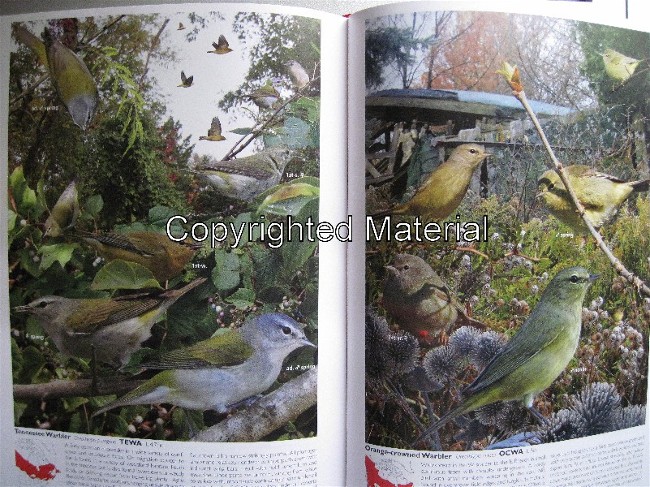

For example, facing plates of the Tennessee and Orange-crowned Warblers provide very useful comparisons between them. What birder has not had to deal with fleeting looks at one of these species? They share some similar and variable features.Their diagnostic undertail coverts are not always evident as they move rapidly through trees and shrubs. In addition to providing a large number of photos of both species in varied plumage, Crossley points out behavioral clues, such as the Tennessee Warbler’s tendency to occur in flocks and often hang upside-down in search of prey, in contrast to the more reclusive and often solitary Orange-crowned species, with its robust and longer-tailed appearance.

Because of their close taxonomic relationship, traditional guides also place the Tennessee and Orange-crowned Warblers next to each other. However, they may show only two or three examples of typical plumage forms for each. For the Tennessee Warbler, Crossley’ Guide displays eight views of perched and four more of flying birds, showing us four distinct plumages as well as typical postures. Six recognizable photos of the Orange-crowned species include variations of three different plumages.

On the other hand, less-experienced birders will welcome the fact that plates of the somewhat similar Blackpoll and Black-and-white Warblers occupy facing pages. Since these two species are not as closely related, other field guides that follow the conventional taxonomic order may separate them by two or more pages of other species. Conveniently, Pine and Bay-breasted Warblers, whose similar appearance may pose a challenge even to the most experienced birders, are located in the two pages just before that of the Blackpoll, with which either might be confused. In the text, plumage differences are analyzed in detail.

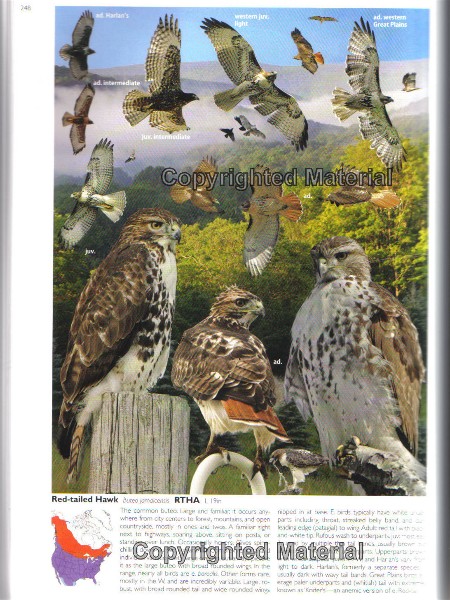

There are several species that exhibit a great deal of variation. The Red-tailed Hawk is one of them:

I compared Crossley Red-tail images and text with those in Sibley’s Guide to the Birds of Eastern North America. The former has 18 images of Red-tails, including flight shots of Harlan’s and western forms. The Crossley text has quite a detailed discussion of the various plumages. Sibley includes 33 images of this species over a two-page spread, including 5 of the dark morph, noting that it is very rare in the east, and 3 of the uncommon Harlan’s, morph. Arguably, Crossley falls a bit short in graphically illustrating the colors, but does better in showing this Buteo’s appearance in flight.

The Savannah Sparrow is another species that shows plumage variation in eastern populations. Crossley provides 10 images, 5 of which are in large enough format to see the birds’ lores. While the amount of yellow seen in the field may vary, it can be a useful feature in identification. None of these excellent images, in varied poses, show yellow lores, but their value in identification is mentioned in the text, along with is a detailed discussion of the plumage, especially the bird’s breast streaking. Sibley has images of 8 Savannah Sparrows, with the amount of yellow varying from none in the Ipswich to quite bright in one. The latter are accompanied by excellent plumage and behavioral descriptions. In both of these examples, Crossley provides large images and very pertinent habitat settings, not possible in the more sparse format of a field guide.

In a departure from the pattern of showing multiple views, an unaccompanied Black Rail lurks furtively in the darkness among the reeds. No open side-on photo, no flight shot– yet a view much better than even those birders lucky enough to have seen one might have wished for. This is the author’s own prized photo– suffice to say it is the only one of this species in his collection (or did he deliberately show this bird, alone and secluded?).

Then there are a few of those delightful and whimsical presentations, such as that of Least Terns swarming around a Cape May lifeboat pulled up on the shore. Comparing the Crossley ID Guide to any field guide is somewhat like comparing apples to oranges. One is not better than the others– the important point is that the book I am reviewing is different… unique, and deserving of a place beside any birder’s easy chair.

Richard Crossley maintains a website with his blog that provides updates and corrections (of which there were only a handful). As necessary, he also elaborates on the captions in the book. I will admit to one disappointment I initially felt after I opened this book. Having watched the promotional video and rejoiced in the brilliance of the screenshots of several plates, I found many of the paper versions of the plates to be quite somber. Sometimes I wished for more light or more detail – even wanted a few of the distant birds to be more clearly recognizable. Some birds were hard to find or partially hidden behind foliage. Wouldn’t this book look better on a computer screen?

This issue is addressed in Crossley’s Introduction: “Just as in real life, the harder you look, the more you will see.” Although an e-book edition would be splendid, I’m pleased to feel the heft of this volume and leaf through its contents. My eyes can scan back and forth between facing and adjacent pages, and down to the text below– and back to a plate to look for that elusive sprite hidden in the shadowy underbrush, “just as in real life.” Being out there sure beats squinting, scrolling and searching.