| PEMBROKE PINES BALD EAGLES |

| Nest Watch Page |

| History of the Eagle Nest |

| Eagle Watch FORUM |

| FAQs |

| IMPORTANT

Since the chicks are almost ready to fledge, we ask observers to spread |

Red in the Morning. View from our back patio. The old sailor was correct– it rained this afternoon!

There was an interesting interaction between the two eaglets this morning. Hope turned 10 weeks old today. Justice is 5 days younger, but appears disproportionately smaller. Hope appeared to wear herself out by flapping and jumping high into the air. Once, she climbed about 3 feet out on one of the branches that support the right side of the nest. This seemed to tire her out, as she settled down out of sight.

(OUR LAWYERS REQUIRE THIS FINE PRINT DISCLAIMER: We really do not know the sex of either chick, but it is common for there to be one of each sex. Arbitrarily, we are considering the older and larger one to be a female, as adult females are, indeed, noticeably larger than males. Ken)

Justice, as usual, “hunkered down” while the older chick was jumping and flapping all over the nest. Earlier, we have even seen him passively tolerate being stepped on by his big sister. Now, as soon as Hope started snoozing, Justice decided it was his turn to exercise.

First, Justice stretches and lets out a squeak:

Ready, set, ……….:

Up, up and away to the other side of the nest (hang 2 ):

And back again to where I started– Oh, Oh! Crash landing right on top of big sister:

But I didn’t do it on purpose!

Enough, enough! It won’t happen again (until next time). Can’t a guy have some fun?

Posted by: Ken @ 10:52 am

| PEMBROKE PINES BALD EAGLES |

| Nest Watch Page |

| History of the Eagle Nest |

| Eagle Watch FORUM |

| FAQs |

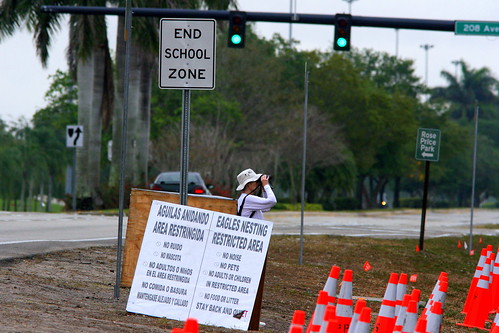

| IMPORTANT Since the chicks are almost ready to fledge, we ask observers to spread their time as efficiently as possible. If you plan to stand watch for an hour or more, please post to the FORUM with your intended hours in the Subject line, so that others can fill in during times that no one is scheduled. OK to post as late as the night before or early the same morning.Thanks! |

The second Cottonmouth I encountered this morning was only about 2 1/2 feet long:

This morning was overcast, breezy and pleasant. Earlier this month a Black-bellied Whistling-Duck flew noisily right over my head while walking the Harbor Lakes portion of the West Miramar Environmentally Sensitive Area that I call my birding “patch.” Its flight sounded labored as it approached me from behind, as I was photographing a butterfly. I thought it was a Muscovy Duck and hardly looked up. It had passed directly over my head. By the time I swung my camera up, still in macro setting, I could not focus on the bird. This Mexican species has spread to areas just north of Broward County , but I was not aware of any local sightings. I believe these ducks usually are seen in flocks, so I wondered if it might be an escaped or feral specimen that are known to be seen occasionally in southernmost Florida.

I photographed these Black-bellied Whistling Ducks last month in the Wakodahatchee Wetlands in western Palm County:

In an effort to document the sighting, I revisited the area several times, hoping to photograph the bird and see if there might be a flock in the area. I have not been able to find any others, but this past week did find a dozen Black-necked Stilts (they flew away before I could photograph them), and today a pair of Blue-winged Teal. These also departed before I could get very close.

Distant Blue-winged Teal:

I approached the ditch along the wetlands path, in the GL Homes portion of the ESL, at several points, hoping to find snakes, especially moccasins, to no avail. I have seen as many as 5 in one morning. The alligator was basking in his usual spot, and slipped quietly into the water before I could take his picture. Returning home on the wetlands path, I encountered a large (4 foot) Cottonmouth Water Moccasin, and further down another smaller one.

Older Cottonmouths turn darker and get quite fat– this one was as thick as my forearm:

The smaller Cottonmouth was reluctant to depart from the edge of the path. Note its dark mask and its vertical pupil (click on image to choose larger size):

A flock of White Ibises flew parallel to the utility wires, creating a pleasant portrait:

Most of the winter, up to seven or eight Northern Harriers have hunted over the wetlands. One adult male was usually present, and the rest were immatures and females. For the past three weeks, there have only been two, a male and a female, probably both in sub-adult plumage, meaning they are not yet one year old. They rarely breed in southern Florida.

I believe this is a female Northern Harrier, subadult plumage, as evidenced by heavy dark streaks on its cinnamon-colored breast:

The grayish back and wings with some brown on its “shoulders,” and black wing tips and black trailing edges of the flight feathers indicate that this is a sub-adult male:

Another view of the male Northern Harrier:

An Osprey wheeled overhead:

At the local Bald Eagle nest site, the older chick, now almost 10 weeks old, was trying out its wings in the nest, sometimes leaping as high as three feet:

The larger chick, “Hope” is in the foreground, overshdowing “Justice,” five days younger:

“Hope” is now about as big as the adults:

An adult Bald Eagle flies by:

| PEMBROKE PINES BALD EAGLES |

| Nest Watch Page |

| History of the Eagle Nest |

| Eagle Watch FORUM |

| FAQs |

| IMPORTANT Since the chicks are almost ready to fledge, we ask observers to spread their time as efficiently as possible. If you plan to stand watch for an hour or more, please post a reply to THIS MESSAGE in the FORUM with your intended hours in the Subject line, so that others can fill in during times that no one is Scheduled. OK to post as late as the night before or early the same morning. Thanks! |

We are pretty sure that we can tell the two Bald Eagle chicks apart. The first egg was laid on December 13 and it hatched on January 17th. The second hatched about 5 days later. Early on, there was a great size difference between the two chicks. For the first three weeks they both sported coats of whitish down. Gradually the down was replaced by black feathers, The younger chick was only a day or two behind its nest-mate in losing the last bit of down, which clung to its head like a white fur skullcap.

Now that both chicks have names and are aver 9 weeks old, the size discrepancy remains. Hope, the older one, also is much more active and aggressive. When a parent brings food, Hope eats first, while Justice usually sits passively on the far side of the nest. After several minutes, he will move toward the adult and beg to be fed. A couple of times his begging appeared to be ignored, while the adult actually fed on the last of a white bird (ibis or egret) that it brought in. Commonly, the adults are simply dropping the prey into the nest and the chicks then tear at it. Justice appears to actively feed himself, though a few times Hope seemed to be keeping him away from food left in the nest. Hope is also more actively flapping her wings and even lifting off in practice flight. She sometimes rises up to two feet vertically. Both take turns rushing and flapping back and forth across the nest.

The adults can be told apart, but the only readily noticeable difference is the larger size of the female. Some say this male’s plumage is a bit darker, but I do not see that. There is a subtle difference in the shape of their bills. I have compared photos and determined the ratio between the height of the bill at is base and the length (from iris of eye to farthest point on the rounded tip). The female has a slightly greater ratio of base to length, a bit over 0.5, while the male’s is less than 0.5. This gives the impression that the male has a proportionally longer and slimmer bill. However, I do not see this in the field, but only in photos where I already know the sex by their size. (I use the eye as a referencce point because it is often difficult to see where the gape of the beak actually starts.)

Here is a comparison. This is the female’s head (she seems to have a more noticeable ridge in front of the nostril):

Here is the male:

These views are not entirely comparable. In fact, look at the male’s bill from a different angle– it appears very thick and short (it also appears to have a slightly more prominent side “tooth”):

Here, Hope watches as the male parent tears off a bit of meat (with feathers attached) before feeding it to her:

The chicks squabble over the food after the parent departs. The smaller Justice is on the left, and has just been struck by Hope’s wing:

Viewing and photography conditions were rather bad this morning, as the gusty wind seemed to always keep some kind of greenery between us and the chicks.

One real treat was the appearance of a flock of 50 to 60 Cedar Waxwings, which wheeled back and forth around the nest tree (note that one seems to be carrying a feather in its bill):

Posted by: Ken @ 3:55 pm

| PEMBROKE PINES BALD EAGLES |

| Nest Watch Page |

| History of the Eagle Nest |

| Eagle Watch FORUM |

| FAQs |

My weekend leisure time was divided between walking our local birding “patch” and observing the local Bald Eagle nest. After one of the driest winters in history, the rains finally arrived.

Sunrise earlier in the week revealed a cloud bank hovering over the coastline, which later worked its way inland, and a cool front set off drenching rain each afternoon:

We were up early Saturday and, before the rains came again, took our “power walk” up the unpaved road that leads to the “patch,” I brought my camera, and after walking about a mile and a half I could not resist the urge to use it. Mary Lou stayed aerobic and walked home, while I took in the beauty hidden in an impoundment in the northeast portion of the West Miramr Environmentally Sensitive Area. [Note: a slide show of photos I have taken at this site is at the bottom of this post]

A Great Egret was reflected in the quiet water:

An immature Wood Stork eyed me warily:

The Great Egret joined an adult Wood Stork and a Great Blue Heron, to complete a pleasing assembly of long-legged waders:

In the distance, three Little Blue Herons flew over the lake:

The Great Egret departed in graceful flight (click on photo for a sequence of images):

I then followed a path that led along a small canal, into the depths of recovering Everglades to the south.

This small alligator (4-5 feet), normally easily frightened, let me approach quite closely:

I obtained an uncommon view of a Zebra Heliconian– the red at the base of its underwings is usually not visible:

The color of this male Julia Heliconian was outstandingly vivid:

Today I arrived at the eagle nest at 1:00 PM, just as the chicks were being fed. The chicks appear to be as big as their parents. They are now nine weeks old:

The chicks are trying their wings! Hope, the older one, leaps into the air:

After feeding the eaglets, the adult flew up to perch and clean its beak in a nearby Australian Pine:

Many Turkey Vultures circled the nest tree. Very likely, they smell the remains of prey that litter the ground beneath the nest, but are unable to penetrate the dense tangle of trees:

Soaked by the welcome rain, “Justice” (the name given to the younger and smaller eaglet) is now about 8 weeks old:

It’s been said that the last thing that science will ever discover is what it is about. Seeking truth, researchers use the “scientific method.” We may take certain things for granted, but if we apply the scientific method to our assumptions and intuitions we may reach exactly opposite conclusions.

Even after I learned to say a few hundred words, I probably still believed that the earth was flat, just as did some very sophisticated adults not too many centuries ago. Before migration was discovered, a plausible explanation for the disappearance of some birds during the winter was that they plunged into the sea to sleep, emerging the next spring. Many other beliefs about the behavior of wild creatures still lack testing and proof.

“Hope,” the larger sibling, is about 5 days older than “Justice.” She appears to have more prominent white markings on her chest:

A parent brings in a prey item, which appears to be a fish, and offers a portion:

“Justice” waits patiently while his older sister (partially obscured behind the tree limb) is fed:

So it is with the newly urbanized Bald Eagles of Florida. As they adapt to the proximity of humans and their activities, what are the limits of their tolerance to disturbance? Certainly (we assume), there must be a limit, an end point at which they will completely avoid us. Walk up to an eagle in the wild, and when we get within a certain distance, it will first show signs of discomfort or anxiety that we might detect. Its eyebrows cannot wrinkle into “worry lines,” because the bony structures of its skull give the eagle a permanent fierce frown. It may exhibit other signs of intolerance– first by staring at us intently, then shifting its posture in preparation for flight, and perhaps by vocalizing, or even defecating to make itself lighter. Then it will fly from its perch, removing itself from the perceived threat. We could measure these behaviors in large numbers of rural and urban eagles, and perhaps note a difference between their reactions at various distances from the intruder.

Mary Lou observes the two chicks from the viewing area, at the edge of Pines Boulevard:

The Pembroke Pines Bald Eagles have already established an “end point” of sorts, by selecting a nest site only about 200 feet from the edge of a busy State highway, with homes, a high school and even a police shooting range nearby. Seventh grade science students at Silver Trail Middle School postulated that the rhytmn of human activity provided a starting point for investigation. Traffic density in front of the nest varies by time of day and by day of week. Can the behavior of the eagles be measured and then correlated with the pattern of vehicular traffic? Anticipating that traffic density may change the habits of the eagles, which behavior(s) indicative of the birds’ anxiety should be observed and recorded? How might traffic density at the moment of such observations be classified?

The students selected the distance of adults from the nest as a relatively easy variable to measure. They chose three variables: “On the nest, in sight of the nest, or not in sight.” This could be a significant factor in nesting success, for if the birds avoid the nest they may not provide sufficient care for the eggs and nestlings. This could even result in abandonment of the nest. For traffic desnsity they decided upon criteria for “Light, Medium and Heavy.” They also selected a 20 minute duration for each set of observations, recording them once each minute. They hypothesized that the eagles would spend less time near the nest during periods of high traffic density.

Of course a study of this sort, if it were to reach valid conclusions, would have to be carried out by an army of researchers at dozens of eagle nests in comparable locations, using randomized observations each day throughout the nesting season. In fact, there are probably few (if any) other identically situated Bald Eagle nests in Florida. Lacking funds, who would volunteer to undertake such an effort?

Out of necessity, the students had to confine their study to non-school hours and within the time constraints of their science curriculum. Their teacher, Kelly Smith, summed up the results of their study rather succinctly. After collecting and aggregating their data, the students

Though their findings were contrary to their original hypothesis, the students know not to draw a scientific conclusion. They did come up with an interesting new idea. Might disturbance actually trigger protective instincts that cause the eagles to spend more time at the nest? The class has been designated to receive a grant from the School District to continue their studies in the next nesting season, when, hopefully, the eagles will return. It would expand the scope of their research to include satellite tracking of a fledgling.

After feeding the chicks, the adult perches to dry its wings atop a Melaleuca snag just to the west of the nest tree:

The dreary skies and rain created problems with photography, but this sepia-toned image was nonetheless striking: