Posted by: Ken @ 3:51 pm

Having been born in the depths of the Great Depression, I acquired some habits of speech that are difficult to shed. I call the refrigerator an “ice box,” and the basement is the “cellar.” Our grandchildren enjoy correcting (ridiculing?) my speech. In my childhood, we made family excursions to visit the summer homes of friends and relatives on the New Jersey shore. Back then, I fed bread scraps to generic “seagulls” and chased generic “sandpipers” along the surf line.

When she was only three years old, our granddaughter spotted a bird flying over just as we were posing for a family photo at Disney World in Orlando. “Seagull,” I casually stated. “No, Grandpa, it’s a gull. there is no such thing as a seagull.” Proud to say, I taught her well, but still fail to practice what I teach. (Can you spot the two birdwatchers in the photo?)

Granted, she had been pointing out and identifying birds from a very early age, and like a sponge, soaked up the birds’ proper names. Here she is, not quite two years old, correctly pointing out a House Sparrow.

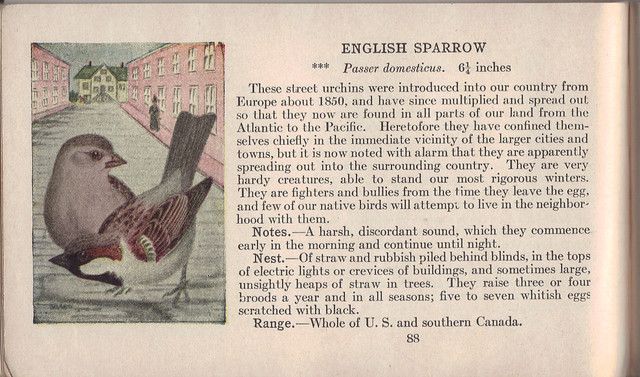

Although I started keeping track of the birds quite early, my skills were initially limited to 20 or 30 of the common land birds in Chester A. Reed’s little pocket Bird Guide: Land Birds East of the Rockies (Doubleday, Page & Company, 1923).

The Guide did not include gulls and sandpipers. To me, it was as if they did not exist. When I graduated to a first edition Peterson Field Guide to the Birds, the small gray-scale illustrations of sandpipers and my inland residence contributed to my lifelong weakness in identifying these species.

“Sandpiper” meant those little robotic things that chased the foam from the breakers up onto the dry sand, and quickly reversed course to follow the foam back into the sea. At first I thought that sandpipers had eternally wet feet. Eventually I learned that this does not hold true all the time, and that some species are quite comfortable away from water for much of their lives.

Least Sandpipers, with their warm brown plumage and yellow feet, tend to favor the muddy edges of ponds.

The similar Semipalmated Sandpiper (with a much larger Yellowlegs in the background) has black legs and a gray back, and spends more time in deeper water.

The elongated shape of the Yellowlegs in the above photo suggests it is a Greater rather than the Lesser species, but the length and shape of its bill is a factor in identification. Here is a Greater Yellowlegs.

This is most likely an immature Lesser Yellowlegs, a bit smaller with a short, straight bill.

During a spring visit to Denali National Park I saw Greater and Lesser Yellowlegs, as well as Solitary, Spotted and Least Sandpipers on their breeding grounds on the tundra, quite removed from large bodies of water. Some perched in bushes, calling and singing like robins and sparrows. (Unfortunately, I had not yet taken up photography).

Around our condo in NE Illinois, temporary pools created by rainwater have attracted Solitary Sandpipers. This one appeared the morning after a heavy downpour.

Spotted Sandpipers stay to breed on the condo property long after the “fluddles” dry up. I photographed this one near our driveway, along the road, from inside our auto.

This past week, following up on reports posted to the Kane County Audubon Society website, Mary Lou and I made visits to a sod farm in Kaneville, Illinois and viewed from a gravel road that runs alongside its eastern border. Along the bare earth where sod had most recently been removed, we saw scores of Killdeer and Horned Larks and up to six Buff-breasted Sandpipers. They are quite handsome birds. This one approached quite closely.

We also saw four American Golden-Plovers, which like the Buff-Breasted Sandpipers*, breed in the Arctic tundra and migrate to southern South America. In fall, the plover must fly to its wintering grounds in Patagonia, a round trip of about 25,000 miles, including 2,400 miles non-stop over open ocean, one of the longest known migratory routes. Both species must build large stores of fat at stopover areas during migration, and their body weight may increase by 30-50% in preparation for the long flights.

American Golden-Plovers are uncommon but regular visitors to NE Illinois. (Click on this link for a video and more views)

I captured a Killdeer, a Buff-breasted Sandpiper and a golden-plover all in the same frame.

*More about the Buff-breasted Sandpiper from Wikipedia:

T. subruficollis breeds in the open arctic tundra of North America and is a very long-distance migrant, spending the non-breeding season mainly in South America, especially Argentina.

It migrates mainly through central North America, and is uncommon on the coasts. It occurs as a regular wanderer to western Europe, and is not classed as rare in Great Britain or Ireland, where small flocks have occurred. Only the Pectoral Sandpiper is a more common American shorebird visitor to Europe.

This species nests on the ground, laying four eggs. The male has a display which includes raising the wings to display the white undersides, which is also given on migration, sometimes when no other Buff-breasted Sandpipers are present. Outside the breeding season, this bird is normally found on short-grass habitats such as airfields or golf-courses, rather than near water.

American Golden-Plovers breed in the Arctic tundra and migrate to southern South America.

In fall, they must fly to wintering grounds in Patagonia, a round trip of about 25,000 miles, including 2,400 miles non-stop over open ocean, one of the longest known migratory routes. They cannot rest on the ocean, as they do not swim.

They must build large stores of fat at stopover areas during migration. Their body weight may increase by 30-50% in preparation for the long flight

They are uncommon but regular visitors to NE Illinois

Photographed at a sod farm in Kaneville, Kane County, Illinois. (Click on image for video and more views).

Photo submission to the BIRD D’pot

Posted by: Ken @ 3:37 pm

The heart of our “Fake Hammock” has been torn out. Note that the cluster of small trees in the background no longer is shaped into a gentle mound. Instead, there is a deep gash in its very center.

Only a year ago, I could sit in this spot in deep shade, an open area under the dense canopy. Then, kids and even their fathers ravaged this quiet spot, pulling down mature trees with chains and driving their four-wheelers into its center. Now all five of the largest trees in the center of the “hammock” have been destroyed by the partying off-road vehicle drivers. The felled trees were all native Tremas, an important winter food source for wildlife in south Florida.

Formerly a sparsely vegetated open area underneath the canopy, my secluded sitting spot is now in full sunlight and invaded by grasses and vines. They hide the fire pit that was fed by the trunks of the felled trees.

Florida Trema fruit is ripening on another tree along the path about a hundred yards away. Note that the berries are in various stages of ripening. This goes on all winter, and a birds are attracted whichever of the trees has the richest bounty.

Several bird species, including this Northern Mockingbird feast on the Trema berries.

A young Northern Cardinal swallows one of the fruits. Its dark bill is turning red and it is molting into adult male plumage.

Common Ground-Doves forage along the unpaved roadway. They often visit the Tremas.

A Common Ground-Dove in flight shows off its bright reddish flight feathers.

Loggerhead Shrikes have not been as numerous this summer.

This gathering of five immature Green Herons is unusual. I have never seen that many together in one tree, in this case an exotic Australian Pine.

The first Belted Kingfisher of the season.

The highlight of our few excursions was our first migrating fall warbler, a Northern Parula male in beautiful condition.

Not to be overlooked on a slow birding day is this female Julia Heliconian butterfly, its camouflaged underwings closed to cover the bright upper sides.

Here is a top view of a Julia female.

The male Julia is much brighter.

Another colorful butterfly is this Gulf Fritillary, on a Morning Glory flower.

Halloween Pennants are very common all summer. The grackles catch and eat them by the thousands.

An Orchard Spider exhibits an interesting color pattern.

Shared on Wild Bird Wednesday

Posted by: Ken @ 10:46 am

This Evening Grosbeak at my front yard feeder in New Mexico (February 2003) was one of my first digiscoped photos. It was taken from inside our living room window through a Kowa spotting scope with a little Canon PowerShot A40– only 2 megapixels! Today I’d be pleased to get such a shot with my ginormous DSLR, but am not expecting to see one in Florida!.

I still have my handwritten notes on my first sighting of Evening Grosbeaks on October 21, 1951, Life Bird #154, a flock of about a dozen at Garret Mountain, N.J. (reservation). They were gathered in a small leafless tree, a sight burned into my memory. In a boastful footnote I quoted Alan Cruickshank’s 1942 edition of “Birds Around New York City: Where and when to find them,” under Eastern Evening Grosbeak.

“Seen… as early as November 15, 1915…and as early as October 27, 1927… but such dates are exceptional as the bird seldom arrives before Christmas, and the large majority of records are grouped in January and February…The recording of this species in the New York City region is still a red-letter occasion, and I know many an active observer who is yet to see this species locally.”

Actually there had been a large flight the previous winter, but none showed up near my home in Rutherford, and I was met with skepticism by the veterans when I reported my sighting to the Hackensack Bird Club at their next meeting in Odd Fellows Hall.

William J. Boyle wrote, in “The Birds of New Jersey” (2011) that there had been major flights since that time into the 1980’s. Only 9 individuals had been recorded in four CBCs since 1998.

I prepared this blog for the ABA “Bird of the Year” Evening Grosbeak Blog Carnival but because of other demands on my time I forgot to post it! However, is is up in time for the Bird D’pot

and Wild Bird Wednesday!

Posted by: Ken @ 6:15 am

We left hot and dry Illinois for hot, humid and rainy Florida a few weeks ago. Most days the weather and other obligations have kept us from getting out into the wetlands.

This sunrise was typical on most days, and the rain was not far behind.

Happily, there were a few clear days that permitted us to take our visiting granddaughters to our clubhouse pool or to explore the wonders of our lawn and garden. The girls had fun chasing after anoles and geckos in our back yard pineapple patch.

Clutching a poor captive lizard, our older granddaughter does not appreciate the irony of this situation as her eyes communicate her displeasure about the Peacock Bass that our next door neighbor just caught. He quickly obeyed her firm command and immediately returned it to the water.

The girls found this odd creature that was carrying what looked like the bodies of a bunch of dead insects on its back. I had no idea of what it was, except that its jaws looked like those of an ant lion. My guess was close. An Internet search revealed that it was the larval form of the related Green Lacewing http://www.freshfromflorida.com/pi/enpp/ento/entcirc/ent400.pdf . It collects the debris to hide it from its prey, mostly aphids, as well as from any enemies such as ants.

With the girls acting as spotters, our back patio has produced a few nice finds. This Tricolored Heron was its usual busy self, dashing here and there in search of prey.

This plunge into the lake yielded hardly an appetizer.

An Anhinga dried its wings next to the lake.

A Great Blue Heron did not fit into the viewfinder.

A neighbor’s rooftop hosted a White Ibis.

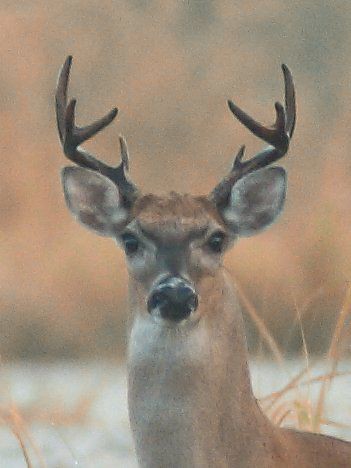

A couple of mornings we got out at sunrise, and were pleased to see a lone White-tailed deer. A bit smaller than those up north, they are not very numerous in the local wetlands. The young eight-point buck posed nicely. My monopod was not ready for this hand-held shot in the morning haze, so I processed it to make up for the blur.

An adult Bald Eagle flew overhead from its nesting territory towards the large lake in our subdivision.

At the heron rookery, this Yellow-crowned Night-Heron chick represented the third breeding cycle of the season. In all, over a dozen broods were successfully raised this year.

An older fledgling stood at an adjacent nest.

A female parent stood watch nearby. Ready for the molt, her feathers show wear and tear at the end of the nesting season.

Green Herons were also quite successful, raising broods in at least four separate nests. This immature bird has a streaked breast and shows a few tufts of natal down.