Posted by: Ken @ 11:07 am

Now that I have become the proud owner of a pair of snake boots, I took up my neighbor Scott’s open invitation to accompany him on a deeper hike into the wetlands adjacent to our homes. This area, located just west of the cities of Miramar and Pembroke Pines, is part of the Broward County Water Preserve, consisting mostly of land that has been set aside by developers to compensate for intrusion upon the historic Everglades by construction of housing subdivisions.

Much of this is land that long ago had been drained and converted to agricultural use, mainly grazing of livestock. Now it is partially surrounded by low levees and managed by the South Florida Water Management District (SFWMD) under supervision of the US Army Corps of Engineers. As part of the Comprehensive Everglades Restoration Plan (CERP), the land was more recently cleared of invasive exotic plants, notably Melaleuca, Australian Pine and Brazilian Pepper. In the portion nearest our home, maintenance appears to have ceased since about 2005, and the exotic Melaleucas are once again spreading into the open wetlands, where they form dense stands.

Under CERP, this wetland will be surrounded by higher levees and turned into a huge reservoir to hold storm water overflow from the planned C-11 impoundment to be constructed ten miles to the north, in Weston. The water depths in this planned lake will vary, depending upon rainfall, from zero to four or perhaps six feet. The objective of this impoundment is to limit eastward seepage of Everglades drainage, thus recharging the aquifer and reinforcing the historic north to south flow of the “River of Grass.” Because of funding and logistical issues, construction of the C-11 impoundment would not begin until at least 2015.

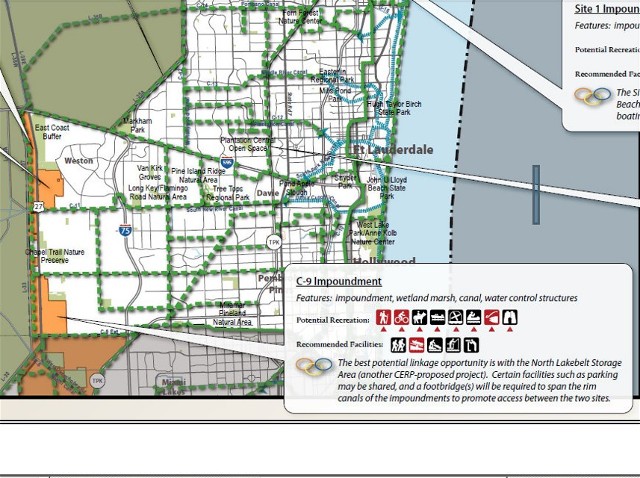

Therefore, our local reservoir (designated as the C-9 impoundment) is on hold for at least ten years. From our standpoint, this is good news, as we now enjoy the presence of terrestrial species that will certainly be driven out when the area is flooded. Here is an informative link about CERP, which includes the following map:

Water levels in our disturbed local wetlands weakly imitate the natural cycle of the original Everglades. An extinct quarry forms a large lake that occupies much of the Harbour Lakes portion of the preserve. Summer rains swell the lake and it spills over into the surrounding Sawgrass meadows. Sawgrass is actually a sedge, and it thrives when the soil is waterlogged for ten to twelve months out of the year.

Water now covers the adjacent Sawgrass meadow. The waterway in the foreground will be a dry to muddy trail by late spring or early summer, but is too deeply submerged for our morning jaunt:

Some parts of the wetland are better drained or are at slightly higher elevations, so their shorter hydroperiod (the length of time that there is standing water) favors beds of periphyton*, algae and other plants such as Spike Rush.

*From: Freshwater Marl Prairie

A complex mixture of algae, bacteria, microbes, and detritus that is attached to submerged surfaces, periphyton serves as an important food source for invertebrates, tadpoles, and some fish. Periphyton is conspicuous and is the basis for the marl soils present. The marl allows slow seepage of the water but not rapid drainage. Though the sawgrass is not as tall and the water is not as deep, freshwater marl prairies look a lot like freshwater sloughs.

A Great Egret stands in this marl prairie, which is covered mostly by rushes:

In January, periphyton floats to the surface as the water level recedes:

The areas free of Sawgrass are richer in nutrients and more friendly for wildlife, such as this American Bittern hiding among the Spike Rushes:

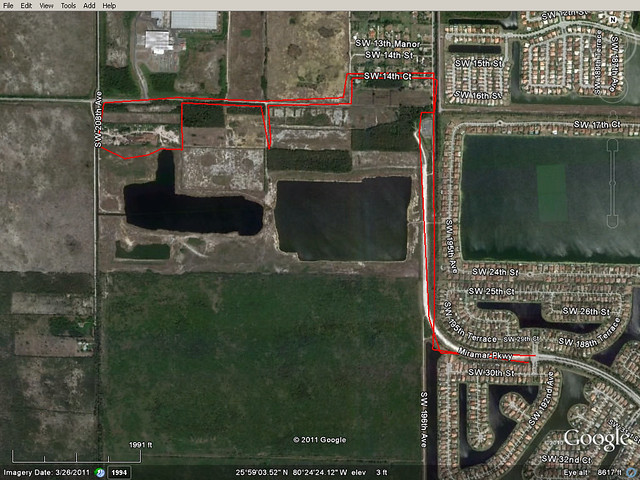

Scott is a “working stiff,” so we met up at 7:30 AM on Saturday. To my surprise he had his little Yorkie, Gordo, on a leash. Gordo was to prove to be a enthusiastic and even useful companion for what turned out to be an ambitious five mile hike. We walked a loop north into Pembroke Pines on the unpaved Miramar Parkway/SW 196th Avenue extension, then cut south and west almost to US-27. At times we found ourselves in water up to mid-shins and sunk into ankle-deep mud. We departed at 7:30 AM and got back around 11:00 AM.

This was our route, beginning and ending at the lower right (SE) corner of the map:

We walked mostly on remnants of old farm roads, which are blocked from vehicular traffic, but often used by recreational ATVs. The cross-country part of our walk was the southern portion of the loop in the upper left part of the map. There, we made very slow progress through a flooded prairie of Sawgrass. We followed animal trails (presumably deer) that tended to make circuits around deeper sloughs and alkali sink holes, but the going got so tough that we considered turning around when we had bushwhacked more than half way to our goal, which was the unpaved portion of SW 208th Avenue that runs north and south (along the far left side of the map). All this time I kept my camera safely tucked away.

As we approached the road we heard dogs barking in the junk yard to the north, and when we finally emerged into the open we were greeted by a pack of eight to ten mixed breed hounds. Thankfully, they were more interested in Gordo, who diverted their attention as we made friendly talk with them and tried to act nonchalant.

Before the dogs actually reached us we encountered a young Cottonmouth in the two-track road (note its bright coloration and yellow tail; older moccasins turn dark with obscured markings) :

I wondered how many snakes we had NOT seen during that part of the hike, and was really happy with my snake boots– except that it turned out that both boots leaked! The walk back was a bit squishy.

A Red-bellied Woodpecker clung to an old telephone pole:

Along the way, a Red-shouldered Hawk monitored our approach before flying off:

Gordo found this pugnacious crayfish along the path. It attacked him, then me as I tried to catch it. They are known to change colors, and perhaps the red reflects its fighting mood (I took it home and it now resides in my aquarium– dull olive brown in color):

Scott and Gordo on this trail, which follows the right of way for Pembroke Road:

Two Painted Buntings flew along the trail in front of us. I only was able to photograph the female, and she was a beauty:

One of a pair of Northern Waterthrushes created a very pretty reflection in a puddle:

Two Yellow-crowned Night-Herons were roosting at the site of last year’s rookery:

Not to be overlooked were this roadside Loggerhead Shrike…

…a White Peacock…

…and a Gulf Fritillary:

By the way, I sent the boots back to the manufacturer, as they were guaranteed 100% waterproof. They have already shipped out a replacement pair. Since they fit well and were quite comfortable (when dry) I will assume my problem represented a sample defect and will withhold any review of the product pending resolution of the issue.

Posted by: Ken @ 9:54 pm

The path that leads to to our favorite birding patch is only a few paces outside the entrance gate to our subdivision. However, we must reach the gate by walking in front of about two blocks of residences. Clothed in our rugged garb, we accept quizzical stares from passing motorists as they bring their kids to school or head for the office, all dressed up. We are often recognized as birders, and have acquired some legitimacy by answering questions from neighbors, such as “Did you notice that a lot of baby white cranes [translation: Snowy Egrets] have just joined their parents [translation: Great Egrets] along our lake?”

Here in Florida we must pay special attention to protection from sun and insects. Sensible wide-brimmed hats, trousers tucked into socks and long sleeves on the hottest of mornings make us stand apart on the fashion scene. (No wonder Mary Lou regarded all birders as rather eccentric folk– until she became one herself! See: “A Valentine for my Favorite Birdwatcher“)

The latest additions to my wardrobe and gear have been an insect-repelling shirt, waterproof snake-resistant boots and an OP/TECH Dual camera/binocular harness. Here I am, all decked out and ready for action (photo courtesy of Mary Lou):

The harness has solved a vexing problem. Until now I have been carrying my camera and binoculars, slung over my neck and opposite shoulders. This can be a troublesome arrangement, Not only do the straps conflict with each other, pinching and constricting my neck all around, but their business ends can become hopelessly entangled. It’s very disconcerting to lift the camera for a shot and find the binocular strap wrapped around the long lens. The harness (or halter) stores the two items of equipment independently on each side, and distributes their weight on a single soft neoprene yoke that goes over both shoulders and is secured by a chest strap. Strangulation is out of the question.

Well, the snake boots are something else. A few close encounters with Cottonmouth water moccasins notwithstanding, I am usually very careful about looking where I step, and am not afraid of any snakes– provided I see them first. My attitude changed a couple of months ago, when (wearing sneakers) I went out in the pre-dawn darkness to try to obtain a photo of one of the Bobcats that live in the wetlands. I forgot to take a flashlight, and depended upon the moon and a little keychain LED lamp to light my way. This was fine until I had to cross some deeper grass and felt that I might be taking my life into my hands. Indeed, another photographer who walked out that way a couple of mornings earlier (and obtained a knock-out Bobcat portrait) told me he saw four small moccassins along the same path. Why didn’t I see any? This experience, and prodding from my spouse, son-in-law and daughter (as well as a couple of birding friends) led me to finally buy the snake boots.

This past Friday, we got out about ten minutes before sunrise and took our usual warm-up “power walk” to the Harbour Lakes Impoundment, a lake about a mile away from our gate. Here, a day-old full moon hovers overhead and the first rays of sunlight have just reached the trees on the far side of the lake:

An Osprey flew over, the early rays illuminating its flight feathers from below:

Along the way, I stopped to photograph a Common Ground Dove…

Truth be told, I just don’t take one picture and move along. Usually, I shoot as soon as I spot my subject, then move in cautiously for better views. Rather than shoot in bursts, I like to catch the bird doing something, such as calling, preening, or looking up, down or over its back. Such poses seem more interesting than simple “field guide” side-on views. If a twig or leaf is in the way, or part of the bird is in shadow, I try to angle around it or wait until the bird moves into a more suitable location. Approaching nearer to the subject requires stealth and slow movements. Each bird seems to have a limit as to how closely it may be approached. (The shrike usually flies off if someone gets within about 30 feet, though there are exceptions). All this takes time and can be very BORING to a non-photographer birding companion. I know this from experience, having taken up photography only recently, and used to hate it when photographers held up other birders’ progress.

Therefore, Mary Lou usually leaves me with my camera and starts birding her way back home within an hour, alone– that’s her, fading away in the distance:

Look closely at the above photo. she is just passing the small, compact wooded area that I call my “fake hammock.” Although it is an isolated area of hardwoods and is dry underfoot all year long, it otherwise bears no resemblance to a “real” hammock, an elevated island in the Everglades, populated by native oaks, mahogany, maples and palms. While my fake hammock contains ligustrum, exotic Brazilian Pepper and lantana, it also has several large native Florida Trema trees (Trema micranthum) with an endless crop of nutritious berries that continue to ripen all winter. These trees are very attractive to wildlife. Visit “Birding in a make-believe hammock”

Trema berries grow along the stems of the tree and are in various stages of ripening:

I had not entered my “hammock” since spring, and found the path that led into it overgrown with high weeds, vines and shrubs. I would never have ventured there without my new snake boots, but I forced my way under the canopy of the trees. Once inside, I found very little ground cover in the rather open shaded area.

An old folding chair had been left there a long time ago and it provided a nice place to sit and just wait for the migrating birds:

I did not have to wait very long, as two vireos suddenly showed up to partake of the Trema berries. One had markings that suggested it might be a Black-whiskered Vireo, but other views confirmed it was a common Red-eyed Vireo with “bad hair”(click on photo to also see a Black-whiskered specimen that I photographed at about the same spot in March of this year:

No doubt about it– they were indeed Red-eyed Vireos:

These were the best open shots I’ve ever gotten of the usually secretive species:

Just above my head, a male Prairie Warbler foraged in a sunny patch of leaves:

A noisy group of three Red-bellied Woodpeckers flew in, allowing me to pull off a couple of lucky shots before they disappeared:

There were very few mosquitoes and no deer flies, and it was almost cool inside my hiding place, as I watched a Black-and-White Warbler work its way towards my position (click on image for more views):

OK, I OD’d on Black-and-Whites. I probably took over 100 shots, almost all through peep-holes between the branches, and most marred by the rapid movement of this little sprite. Then it came into the open and I finally got some full views:

A Northern Parula peered down at me from the canopy:

Another brightly colored male Parula joined him:

The Blue Jays have completed their molt, and this one looked sleek and handsome:

Blue-gray Gnatcatchers were almost as distracting as the many butterflies that fluttered in my peripheral vision:

A Brown Thrasher was a surprise visitor:

This Great Crested Flycatcher preferred to perch against the sun and sky, providing me with only severely back-lighted soft images:

For me, the real treat was a pair of Ovenbirds that chased each other back and forth, rarely sitting still long enough for decent portraits; this one insisted on hiding behind a leaf as it eyed me:

The other Ovenbird never perched nearby, requiring me to shoot through holes in the foliage into its shaded retreat:

This tailed butterfly is a Dorantes Skipper:

Posted by: Ken @ 3:59 pm

Last week, while I was still in Illinois, I received an e-mail from Michael Fullana, a professional photographer who lives near our Florida home. He had seen one of my Bobcat photos on the Internet and was surprised to learn that they could be found so nearby. I gave him detailed instructions and within a day or so he was out before dawn in the wetlands next to our subdivision. He was able to get two photos of a very handsome Bobcat a little after sunrise.

Bobcat (c) by Michael Fullana:

Creative Edge Photo www.creativeedgephoto.com Used with permission

Obviously, Michael’s photo was to die for, so I planned to get out early myself on the first morning that we did not have medical and dental appointments. Today we finally had no other obligations or early rain.

It was pitch black and there were no clouds when I left the house at about 5:20 AM, slathered with mosquito repellant. Away from the street lights, I walked along the unpaved roadway with a bright half-moon directly overhead. When I got to the spot where I usually cross over a berm into the protected area near the 196th Avenue Canal, I hesitated because it looked unfamiliar. The grass had grown quite high since my last visit over six weeks ago, and I have seen Cottonmouth moccasins here. It was just too dark. I had a little LED light on my key chain, so I used it to illuminate each step until I got on the open path where the moonlight revealed much more detail. It was too dark for me to proceed south on the trail along the levee where Michael had noted many Marsh Rabbits, a favored prey for Bobcats.This morning there were no rabbits to be seen– a bad sign? I tried to test fire my camera and there simply was not enough light.

Distant lightning flickered from a storm over the Florida Keys.As I waited in the dark, I noted the sounds around me, over the drone of mosquitoes. Tree frogs and geckos chirped like little birds. Purple Martins calls drifted down from the black sky. Night-herons squawked in the darkness. The first bird song I heard was the “Drink Your Tea” of an Eastern Towhee. Cardinals soon followed, along with one Carolina Wren. Mockingbirds were strangely silent. Boat-tailed and Common Grackles added their poor excuses for songs, along with a few Mourning and White-winged Doves.

In summer, here in the sub-Tropics, as Kipling said, “dawn comes up like thunder.” With the first bare glimmer of red in the east I attempted more test shots at various settings, but the shutter would not click.The sky rapidly lit up, and by about 5:50 AM I could get grainy exposures at ISO 3200, so I started walking slowly along the levee path. Mike said he got his photo at around sunrise, which was at 6:42 AM. I walked the quarter of a mile to the spot where he (and I, on several previous occasions) had seen the Bobcat. By then I could reduce the ISO to 1000 and take decent flash shots, pointing away from the path. My chosen vantage point was just off the main trail with my back to the east. One step forward permitted me to look both ways up and down the levee trail, which runs north and south. Directly in front of me, a side trail, already partially under water, led westward, deep into the wetlands. I waited, cautiously peeking from side to side every few seconds.

Suddenly, at about 6:20AM, I saw what I thought was a deer grazing at the edge of the path to the south. Forgetting that the flash was still on, I raised the camera and popped off a shot:

The animal immediately looked up and I realized it was not a deer:

When I checked the photos on the camera’s LCD display I saw the eye shine and realized the gravity of my error. The cat stayed in place for a few more seconds, and I took several photos without the flash:

The above was the best of a batch of poor exposures. Because of the low light, there was considerable camera shake at ISO 1000. Worse, I auto-focused on some branches in front of the Bobcat. My manual focus shots were no better in the poor light. Vision problems with my right eye have limited my ability to focus sharply, and I just cannot get used to shooting with my left eye, as the camera is not friendly that way. Well, I will certainly try again, but not get out quite so early, and also will be extra careful about using auto-focus!

On the walk back along the path, I stopped to photograph this male Queen butterfly:

A small bird flitted right across my field of view just as I depressed the shutter. It was a Carolina Wren, elusive as usual:

Nearby, a Loggerhead Shrike was surveying its territory from atop a Melaleuca tree:

A female Prairie Warbler was carrying an insect, almost certainly to feed a nearby nestling or fledgling:

Prairie Warblers breed locally, and are one of the few warblers we get to see during the summer. After moving back and forth between trees with the insect in her mouth, she ate it, perhaps to help conceal the presence of its young. I have seen such behavior before in other species, though it would be hard to prove its motivation:

Before heading home, I turned north on the unpaved stretch of Miramar Parkway/SW 196th Avenue and visited the Harbour Lakes impoundment portion of the wetlands preserve that I call the West Miramar Environmentally Sensitive Land (ESL).

The reflection of a Great Egret highlighted the still water along the opposite shore:

A Red-winged Blackbird sang “Conk-ra-lee!” at the edge of the lake:

This Florida Box Turtle was crossing the gravel road while the sun was getting higher and hotter. As I approached I heard him hiss when he saw me: “(Oh) Shhhhhhi…t!” He tucked in his head and legs and looked out only after several minutes had passed:

He might be slow, but his eyes sparkled with life:

After I took these photos I carried the turtle over to the shade of a grass clump on the side of the road. I turned away and within seconds he was actually running to the safety of the deep grass further back from the road!

Posted by: Ken @ 5:47 am

Readers have probably noticed that I take most of my photos in birding “patches” very close to home, mainly in the adjacent water conservation area that we call the West Miramar ESL (for its designation by the South Florida Water Management District as an environmentally sensitive land or area). Rather than chase after rarities, we usually wait for the birds to visit us. Pretty soon we will respond to our own migratory urge and try to catch up with them up north.

We enjoy the birds, but we also like being in the places where the birds are– mostly scarred remnants of former natural beauty, but places where we can briefly ignore the sounds of lawn mowers and leaf blowers and hear splashing on the lake and the songs of cardinals, yellowthroats and towhees. We like getting out early, around sunrise, and walking fast before stopping to watch and listen.

On the first of January this year I reflected on the fact that now I have lived a portion of my life in each of the past nine decades. This does not make me 90 years old, but it means that I was born in the middle of the Great Depression and accounts for my compulsion to get up and out and make the most of every day.

Depending upon the birds to come to us creates a sense of urgency during migration. We must be out there to greet them. Earlier this week we learned we could not predict the arrival of flocks of warblers in our neighborhood. Trying to anticipate the perfect morning for birding during migration, I keep track of the weather radar. So far there has been little correlation between the abundance of migrants in our neighborhood and the density of the flocks that appear on the radar screen.

For example, on April 14 we saw nine warbler species, as reported in our previous blog. That night the radar looked very promising. It appeared that migrating birds had piled up on the northern coast of Cuba and had begun their flight across the Straits to Florida at sunset. We hoped that the next morning would be even better for warblers.

Here is the Key West radar image covering the period between 9:30 and 10:38 PM EDT on April 14th:

Angel and Mariel track migrants on radar in their blog, Badbirdz2. They reported “Heavy Migration Over Florida” and their overnight radar loops documented the continued passage of migrating flocks over south Florida, including our home, into the early morning hours. We got out early, expecting to be surrounded by colorful warblers. I hid inside the “hammock” for two hours, and saw many, many catbirds that may have helped cause the radar echoes, but not a single warbler, or other migrant!

Before Mary Lou abandoned me at the “make-believe hammock,” we had visited the lake at the far end of the unpaved road into our patch, where we found a small flock of Least Terns. A pair of Least Terns posed nicely on a rock:

They flew back and forth in front of us, allowing me to practice taking in-flight telephotos with my new Canon 60D:

The smallest of the terns, the Least Tern has a proportionally long bill and short tail, and in breeding plumage has a black cap and sharply contrasting white forehead:

I caught a Red-winged Blackbird in mid-song, his partly spread wings showing off bright red epaulets:

The light was behind this Tricolored Heron as it watched us warily:

A Green Heron joined the terns along the edge of the lake:

Two days earlier, I was so engrossed in photographing the terns that I forgot a cardinal rule– never take a step without first checking the surroundings. Out of the corner of my eye, I caught the slow movement of a snake, only about three feet away.

It was a poisonous Cottonmouth water moccasin:

Of course I stepped back as the snake coiled into a defensive posture. It opened its mouth and began to regurgitate what looked like the tail end of a siren (a common legless amphibian). This may have been in response to the stress created by my disturbance:

Like cats and other nocturnal predators, all the North American poisonous snakes (except for the Coral Snake) have elliptical pupils. This is an adaptation to night vision, allowing them to protect their sensitive eyes by shutting out almost all the light if necessary:

Snakes are fascinating creatures. Cottonmouths eat a great deal of carrion, and are not aggressive. They are inconspicuous, and about the only way to get bitten is to touch one or step on it unawares. As a sad footnote, when we returned to this spot we found a Cottonmouth, probably this same snake, crushed by boulders:

Yes, it is poisonous, and some guy now thinks he’s a hero, but I don’t think that the world is made any better by senseless killing.

As a kid, I used to step on any ant I saw on the sidewalk, for sport, or maybe to make it rain.

Such a habit may have persisted in my subconscious mind. Several years ago, while leading a group of 8 to 10 year old kids on a nature walk at Rio Grande Nature Center in Albuquerque, I casually stepped on an ant– I must admit it was an intentional act.

One of the kids immediately asked, “Why did you do that?”

“Do what?”

“Step on that ant.”

I could only reply, “It was wrong for me to do that– the ant was minding its own business and wasn’t doing anything to hurt me.”

Why did I do that? It was a simple but profound lesson for me. I had extinguished a tiny spark of consciousness, and my universe had been diminished, be it ever so slightly.

Posted by: Ken @ 12:32 pm

On our walks, Mary Lou and I often try to find “target” birds. All winter, a male Painted Bunting is a “must see” for her. This time of year I am especially looking for Savannah and Grasshopper Sparrows. Neither of us got our wish when, around sunrise one morning this past week we set out to our local wetlands.

We actually did not have very high expectations. The air was still, which helps us see small movements of foliage that can betray the presence of a small bird. However, a light fog impaired visibility, and the birds were either absent or unusually quiet. One thing you learn about the wild world is that beauty surrounds you under any conditions– but you sometimes have to look very hard.

Pearly beads of dew festooned this spider web:

We walked on to the edge of the Harbour Lakes impoundment, about a quarter of a mile north of our usual birding patch. The sky turned bright blue and the fog was beginning to clear. Mary Lou spotted movement along the shore, then exclaimed that a snake had entered the water. It took me a while to even see the creature, and by then it was swimming away from us.

Characteristically, this Cottonmouth Moccasin swims with its bulky head held high above the surface of the water:

Two male Boat-tailed Grackles crossed swords in a territorial confrontation:

On an adjacent rock, two sleeping Greater Yellowlegs woke up as I approached:

A Tricolored Heron was doing an erratic “dance” as it darted after a school of small fish:

This Little Blue Heron was struggling to subdue a large and very active siren:

Sirens are considered to be the most primitive living salamanders, and their ecology and natural history is poorly known. Completely aquatic, they lack rear limbs, and keep external gills throughout life.

From an Internet search I learned:

These giant salamanders are often confused with eels. In fact, you may hear people call these salamanders “mud-eels” or “ditch-eels.” However, eels are a type of fish with obvious fins running along their back and underside. Salamanders are amphibians. Amphibians have limbs and no fins. Also, giant salamanders are easily distinguished from aquatic snakes because their skin is smooth, slimy, and lacks scales.

Finding nothing more of note, we headed back to the wooded area to see if birding might have improved, now that sunlight was waking up the insects. To our surprise, there were flocks of warbler, mostly Yellow-rumped and Palm Warblers. Prairie Warblers, notably scarce since the cold snap in December and early January, were back in good numbers.

The Palm Warbler has long legs, an adaptation to its habit of spending much time on the ground:

This Prairie Warbler ’s bill shows the results of foraging on some berries that were covered with fine white powdery mildew:

I must have taken over 20 photos of the Prairie Warblers– Pleased that they had returned, I could not get enough of them:

Another Prairie Warbler struck an unusual pose as it eyed me quizzically:

We saw two Orange-crowned Warblers. This one was also a contortionist:

This Orange-crowned Warbler looked like it might be a Tennessee Warbler at first, as I could not see any yellow under its tail. When I reviewed the photos I was able to confirm that it had yellow under-tail coverts, as well as an eye-ring that is broken horizontally by a faint dark stripe.

An Orange-crowned caught a juicy spider– I hope it was not the one that spun that beautiful pearl-studded web!

This photo of a Blue-gray Gnatcatcher turned out to be rather contrasty against the bright sky, but I loved the way the out-of focus grass in the background caught the sun:

A Ruby-throated Hummingbird thrust out its tongue just as I clicked the shutter:

There are some sure signs that spring will soon be here. A Yellow-rumped Warbler perches on a Red Maple bursting with little red “helicopters”:

Perhaps stimulated by the lengthening days, a male Northern Flicker appeared to be courting a female and was drumming on someone’s roof drain, until it flew up to the broken-off top of a Royal Palm:

The exotic Egyptian Goose is a member of the shelduck family (thus more closely related to Muscovy Ducks rather than true geese) that is is native to Africa. Regarded by Florida Fish & Wildlife as “escapees,” they have been documented breeding in various parts of the state. They tend to nest in secluded areas, and are very aggressive in nest defense and in competing for food. They were first seen in Broward County in the 1960s.

This is one of a pair of Egyptian Geese that I have seen twice before, flying together over the wetlands next to our home, but this is my first photo documentation:

A stop at our local Bald Eagle nest found both chicks to be healthy and growing fast. The oldest was 26 days old when I captured this short clip of the nest-mates: