Posted by: Ken @ 2:12 pm

Among my fondest birding memories are those of spring migration when I was a youngster in New Jersey. The trees were just leafing out, and numerous warblers in vivid plumage adorned the branches. The air was filled with song, and the show changed almost every day, beginning with the early arrivals, such as Myrtle (now called Yellow-rumped), Palm and Black and White Warblers, followed by a slew of other warblers, orioles, buntings, and grosbeaks.

Spring migration can be very slow in our south Florida neighborhood. We are experiencing the gradual departure of most of the small species that spend the winter here. Out-migrants greatly outnumber in-migrants. Gone are the kingfishers, the kestrels, and most of the Yellow-rumped, Prairie and Palm Warblers that were so common during the colder months. Within a few weeks the only bird in our yard that is smaller than a Blue Jay or shrike will be a Red-bellied Woodpecker or an occasional starling. We don’t have any sparrows– not even House Sparrows!

Loggerhead Shrikes are becoming more numerous:

Male Red-winged Blackbirds are being joined by their mates as they relocate to territories in the wetlands:

We live about 18 miles inland from the ocean. Local habitat is badly degraded. Our housing development was gouged out of land that was originally Everglades. Much of it had been drained and put to agricultural use by the middle of the 20th Century.

The homes in our neighborhood were constructed only about 10 years ago, elevated above the flood level on rock and sand, excavated from quarries that became the lakes such as the one in our back yard. To mitigate the environmental damage, the developer had to set aside undeveloped tracts to serve as water conservation areas.

Each home has one mandatory native tree (ours is a Mahogany), but just about every other plant is an exotic. Groomed St. Augustine lawns extend to the very margins of each lake, and alien fruiting and flowering trees and shrubs predominate. The water conservation areas are overrun with invasive Australian Pines and Melaleucas, imported to draw water out of the wetlands, and Brazilian Pepper, an ornamental shrub run amok.

At the western edge of our subdivision, our birding “patch” has one small thicket of mostly exotic shrubs spared by the gardeners, providing shelter for transient migrants:

Prairie Warblers breed in south Florida, especially in coastal areas, and we welcome many additional migrants to our local birding patch. They had been getting scarce since early March, but this week a small flock of warblers moved through the row of Live Oaks that run along the top of the berm (to the right in the above photo).

The flock consisted mostly of Prairie Warblers, which keep their bright yellow plumage all year long:

Among the other warblers were several Northern Parulas, including this male:

Female Northern Parulas lack the black “necklace” of males, but are no less beautiful:

This Prairie Warbler, about to capture a spider, seemed to look curious about my presence, and struck an almost comical pose:

Palm Warblers are the most common small birds around suburban dooryards– some locals call them “Florida Sparrows:”

While most Palm Warblers we see here during winter are dull birds of the western population, sometimes a representative of the bright eastern race shows up during migration:

Yellow-rumped Warblers arrive in dull winter and immature plumage, but the males begin to brighten up before departing:

Pine Warblers may be found all year around in suitable pine and mixed forests, but during winter their numbers increase as they are joined by migrants. They may be found locally in ornamental Slash Pines and park land.

A cooperative Pine Warbler posed in a small pine along the boardwalk at nearby Chapel Trail Nature Preserve:

This past week, a five-foot alligator appeared on the undeveloped side of the lake bordering our subdivision. Unless it climbs back over the levee into the wetlands, it will not long for this world. If residents with back yards on the other side see it, they will call for its removal:

The lack of suitable habitat is not the only reason for our paucity of migrants. In Spring we do not see as many “through-migrants” as we do in the Fall, when southbound birds usually will avoid flying over water until nightfall. Therefore, they wait for favorable weather along the southern tip of the peninsula, and even may back up into our neighborhood. For updated reports and radar images of Florida migration, visit Badbirdz-Reloaded.

In the fall, incoming flocks often become “over-migrants.” The reason? The flight to here from Cuba and the Bahamas is rather short. Cuba is only 90 miles south of the tip of the Florida peninsula. In good flying weather, this is a mere 3 or 4 hour flight for migrating birds. Flocks congregate along Cuba’s north coast. Most depart north shortly after sunset, reaching Florida before midnight. They are able to fly many more miles, overland or along Florida’s coastlines, reaching the northern part of the state by dawn. Those that encounter headwinds or depart Cuba later during the night may stop on the Florida Keys or along the coast at daybreak.

Hawk with a full crop, at a (short) distance:

Now back up a bit. Can you identify this hawk– er, raptor in flight?

Well, that was easy. This one should not give you any trouble, either (click on photo for more information):

Now let’s step way back and try again.

Birders can attach too much importance to color and plumage markings in identifying a bird. Soon after moving to Florida from New Mexico, I made that mistake when I looked up and saw this hawk, obviously a Buteo with a red tail (no cheating– don’t hover over the image to find out its name):

Naturally, I thought that the color of the tail had sealed its identity. It was, after all, a “red-tailed hawk,” pure and simple. I noticed it looked clear underneath, but thought that maybe Florida had some Red-tails that were even lighter than those I knew out west. Patagial markings? Belly bands? Were they all that important? It had a RED tail. Case closed. I took its picture, and then tried to ignore a nagging doubt. Only after I viewed the hawk on my camera’s LCD screen did I realize it was a species that I had never seen before in its light plumage variation. Its tail contains no red pigment, and the red color is attributable to back lighting and diffraction. Click on the thumbnail to obtain a better view, and learn the hawk’s identity.

The following hawks are displayed as thumbnails, to introduce my review of Jerry Liguori’s Hawks at a Distance. As a warmup for my review of this book, here are a few more of my images of “hawks” in flight. Test your ID skills. No cheating– do not “hover” over the images until you are sure of your ID.

Click on images if you wish to enlarge the views:

In the fall of 1961,when I was an intern at Mountainside Hospital in Montclair, New Jersey, our chief of thoracic surgery was Dr. Adrian Sabety. (who passed away only last month in Sanibel, Florida at the age of 95). Dr. Sabety was an ardent birder, and he invited me to accompany him on a visit to a nearby hawk watching site. It occupied undeveloped land on a ridge in the Watchung Mountains. The site was accessible by means of an overgrown trail, and upon reaching the top, I was amazed to take in an unobstructed view of the sky in all directions, including the full skyline of New York City..

Even more impressive was the skill of the small cadre of hawk watchers who called out the identity of the raptors as they were carefully tallied. I returned several times, with my latest copy of the Peterson Field Guide in hand, trying to sort out the hawks as they flew over. It was fairly easy for me to distinguish the many Broad-winged Hawks from non-Broad-wings, even at some distance. Except for identifying vultures and the occasional Red-tailed Hawk that flashed its tail color, this was about as far as I was able to advance my skill set. The Montclair Hawk Watch has since become an official sanctuary of the state Audubon Society, and it enjoys the distinction of being second in longevity only to Pennsylvania’s famous Hawk Mountain.

My last visit to Cape May, New Jersey coincided with the 2009 fall Hawk Watch. The observation deck was crowded with watchers, armed with binoculars, spotting scopes and cameras. A continuous stream of southbound raptors appeared over the horizon. Often the hawks appeared as specks above the distant horizon, at first only visible to one or two people. Binoculars turned the little specks into larger specks. Pete Dunne was there, acting as a coach, pointing out identifying features, such as the more powerful appearance and swift direct flight of Merlins as opposed to kestrels.

Pete Dunne and hawk watchers at Cape May, NJ, October 10, 2009:

Relatively few of the hawk watchers had the confidence (or the braggadocio) to call out the identity of the specks in the distance. Keeping my opinions to myself, I actually picked a Merlin out of the crowd, and watched it pluck a Tree Swallow right out of the air and carry it down to the lighthouse for a leisurely meal. No one else knew, but I only had about 50% success in telling big female Sharp-shinned from small male Cooper’s Hawks– a flip of the coin would have done as well.

Jerry Liguori’s Hawks at a Distance: Identification of Migrant Raptors is certainly a book for aspiring as well as veteran hawk-watchers. But, is it a book for a recreational birder like me, who rarely encounters a kettle of Broad-winged or Swainson’s Hawks, and is intimidated by the robo-watchers atop the mountains and lookouts? My short answer is yes, and let me tell you why.

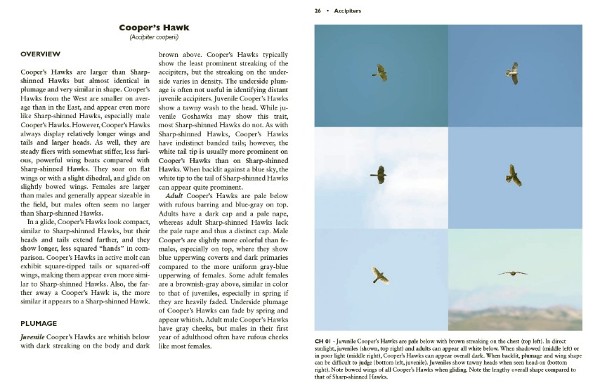

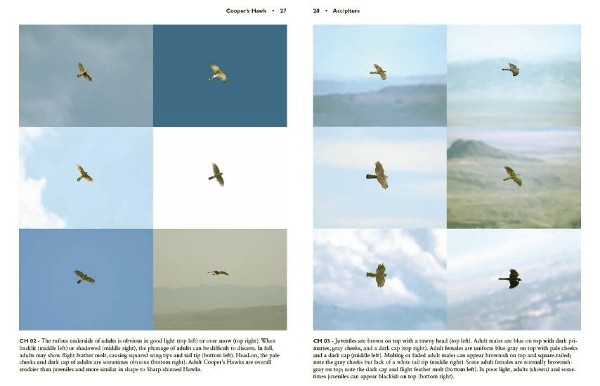

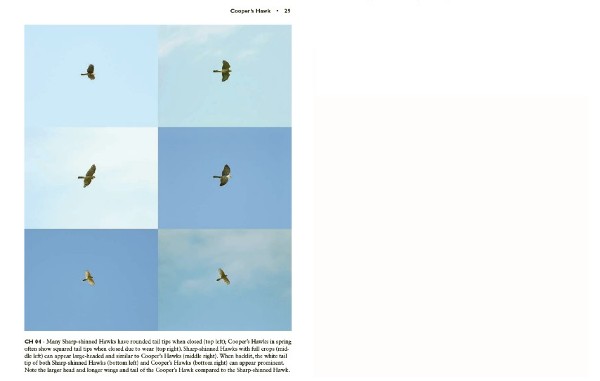

The book is unique in that all the birds are photographed in flight. Except for the full page color plates that introduce concise descriptions of each of the 20 raptor species most commonly seen in established hawk watching sites, the color photos are tiny, usually six to a page with lots of sky in between the images. An additional nine less common migrants are also described and depicted in distant flight.

The hawks are seen, not only from below, but coming at you and going away, from the side and sometimes from above. At the back of the book, individual pages with over 40 black and white photos are devoted to each species, illustrating the bird as semi-silhouettes in every conceivable flight posture and alignment.

As I initially leafed through the array of images, many looked identical to me, as if all were taken of the same bird, no matter what species I was looking at. I realized that browsing this book did not yield much useful information. I took a different tack, and started reading the sections on particular raptors that were most familiar to me: kestrels, harriers, Red-tails, Red-shouldered, Sharpies and Coops. On the first reading of the descriptions, I paid special attention to statements in bold text. Now the book began making sense, at least for the hawks with which I had some experience in observing.

Suddenly, Jerry Liguori was my coach, just as was Pete Dunne that day in Cape May. In bold print, he called out the most important identification features. American Kestrels are “dainty, slim overall, and lively and nimble in flight,,,” with wings that are “smoothly curved but hunched timidly at the shoulders.” Northern Harriers are “extremely buoyant… and “nearly always hold their wings in a prominent or modified dihedral.” And so on…

As I read and re-read the sparse text, the tiny photos started to come alive. The finer points of identification became relevant and interesting. Now I cannot wait to test my memory in the field and look at some old friends with new appreciation.

This book reminds me of the manual that came with my new camera. I skimmed the online version before I ordered the camera, and referred to it again before the camera arrived. Then I browsed through the paper manual when it came in the box, trying to memorize the names, positions and functions of all the buttons, dials and displays.Still, the first time I used the camera, it seemed I had forgotten nearly everything. However, after just that one real-world attempt, the advice in the manual took on new meaning and importance. Each time I go back to it I have a question or a problem that needs resolution– but my visits to the camera manual are less and less frequent.

Hawks at a Distance (Princeton University Press) lists at $19.95 for a sturdy paperback edition, but may be purchased from Amazon.com at a discount. A Kindle version is also available.

Here are some sample pages:

Posted by: Ken @ 5:42 pm

A little more than an hour’s drive from our south Florida home, Corkscrew Swamp is located within the largest remaining virgin Bald Cypress forest in North America. A boardwalk provides access to six distinct habitats: pine flatwood, wet prairie, pond cypress, marsh, lettuce lakes, and bald cypress forest. Enjoy a virtual tour of the 2 1/4 mile boardwalk at this link.

Entrance sign:

Several Painted Buntings were visiting the feeders at the back porch of the Blair interpretive Center:

The large and graceful Palamedes Swallowtail is a hallmark species in southern swamps:

The boardwalk loop begins and ends in the flatwoods, where Slash Pine, Cabbage Palms and palmetto predominate in the dry sandy soil. Several woodpecker species may be expected here. We saw three or four Pileated Woodpeckers, but none of them posed for my camera.

This Pileated Woodpecker appeared right next to the boardwalk during a prior visit to Corkscrew:

We heard the songs of many White-eyed Vireos, but only this one, in a willow at the edge of the wet prairie, provided a photo opportunity:

Here’s a better view of the vireo’s namesake eye:

As we crossed the wet prairie, a Red-shouldered Hawk flew over the boardwalk. Note the white comma-shaped patches near its wingtips:

The hawk roosted in a Slash Pine. It is wearing a leg band:

Wild Blue Flag Irises bloomed in the shade of the Pond Cypress trees:

Numerous Common Grackles were busy carrying nest materials. Other small birds abounded. Among them were Northern Cardinals, Northern Parulas, Palm and Pine Warblers, Downy and Red-bellied Woodpeckers, House and Carolina Wrens, Eastern Phoebes, and Blue-headed Vireos.

In the Bald Cypress forest, We saw at least a half dozen Tufted Titmice, and heard the songs and calls of many more:

Although the parula warblers foraged high in the canopy, several Black and White Warblers gleaned the cypress trunks:

Great Crested Flycatchers were quite vocal, but it was difficult to catch sight of them:

The calls of Red-shouldered Hawks resounded through the forest. This one posed on a cypress branch at the edge of a small clearing:

Nearby, a volunteer naturalist pointed out a Red-shoulder’s nest containing two downy chicks:

As the boardwalk skirted the lettuce lakes (actually an open-water slough, its surface coated with aquatic plants), we spotted a drowsy Yellow-crowned Night-Heron:

A Great Egret’s white plumage contrasted nicely with the floating water lettuce and duckweed:

The egret flew up to preen in a small tree, showing off its breeding-season plumes:

Fair game for the herons, a Green Tree Frog hid in the vegetation at the Lettuce Lakes:

Not far away, a Striped Mud Turtle basked in the sunlight:

A second look at this off-white heron revealed a bluish bill with black tip, characteristic of a juvenile Little Blue Heron:

Swallow-tailed Kites spend the nights in large roosts near the sanctuary. Many wheeled overhead, but I found it impossible to capture them through the leaves of the cypress trees.

This is one of my earlier images of this graceful raptor:

Sadly, no Wood Storks were present. This should be the height of their breeding season, but they have failed to breed at Corkscrew for the second season in a row. The reasons for this failure are not entirely understood. This winter’s drought, the worst in 80 years, and near-freezing temperatures in mid-winter very likely contributed to this year’s failure. The winter of 2008-2009 was a banner year for the storks at Corkscrew. Visit this link for historic records and more information about the exacting conditions required for successful reproduction of the storks: Wood Stork Nesting Data for Corkscrew Swamp Sanctuary, Also see Struggling Storks, which discusses their unique habitat requirements.

Over a year ago, a large number of immature Wood Storks, products of the successful 2008-2009 season, spilled over into our neighborhood, decorating this dead tree near our home:

I shared the joy of the sightings with John and Barry on this delightful morning:

Posted by: Ken @ 8:34 pm

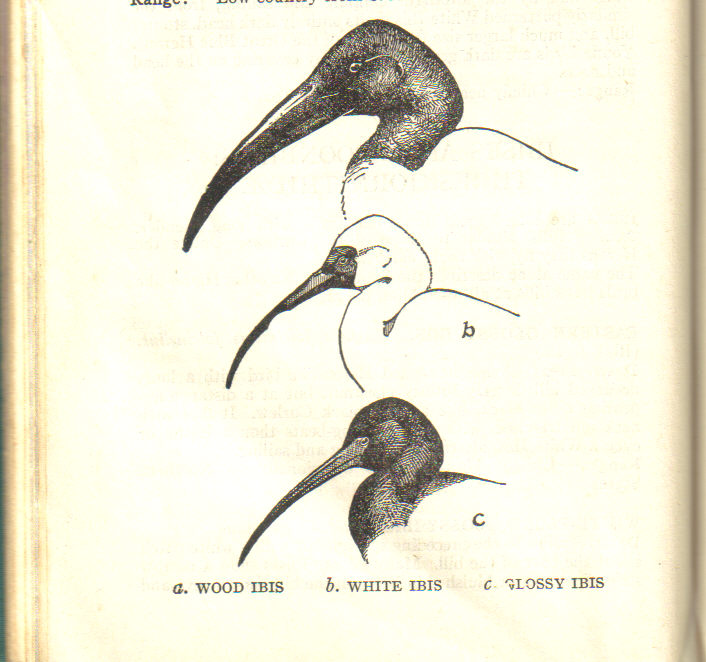

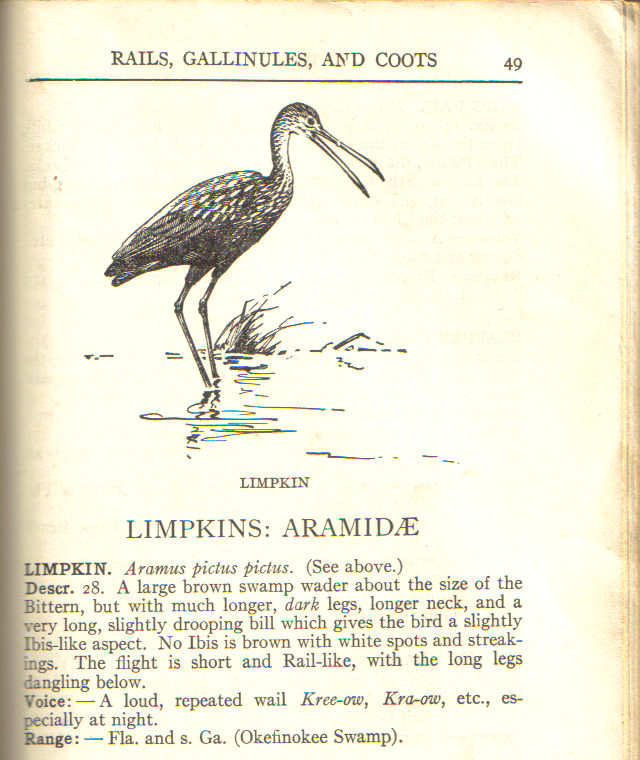

As a child, back in New Jersey, I often took vicarious birding trips to the sub-Tropics. Roger Tory Peterson was my virtual companion (See my review of Birdwatcher: The Life of Roger Tory Peterson). I remember looking through my 1939 Peterson’s A Field Guide to the Birds at such exotic southern birds as the Wood Ibis (now properly known as Wood Stork), White Ibis and Limpkin. None of these three were included among Peterson’s glossy plates. The former appeared as an ink drawing of its head, comparing it to the White Ibis, which also was not otherwise depicted. (The Reddish Egret, another Deep South specialty, was considered to be so rare that it did not even deserve an image).

A Limpkin was shown calling, and Roger described its cry as “A loud, repeated wail, Kree-ow, Kra-ow , etc., especially at night:”

All these birds had two things in common: they were long-legged waders that I imagined moving through still water among moss-draped trees, and I held out little hope of ever seeing any of them. In those post-Depression days our travel was constrained by the limitations of our family car, a 1937 Ford sedan that already was showing signs of age. Its exhaust pipe spewed blue smoke, and Dad carried at least a couple of spare rebuilt fuel pumps and extra inner tubes so that he could install replacements when they failed on the road. (I eventually inherited this car and its problems, some aggravated by my own foibles: (Chickie the Cops!)

For our family, Florida was indeed a far-off place, as were destinations anywhere north of Derby, Connecticut, west of Philadelphia or south of Washington, DC. I held hopes of one day seeing a Northern Mockingbird, a Tufted Titmouse, or a Carolina Wren. Now, all three species are common there, but in my day they were rarely observed in the northern part of New Jersey. Happily, the Northern Cardinal, which disappeared from its northern range during the early 1900s, (presumably driven out by severe winters) began to repopulate the area around New York City in the mid-1930s and had become quite common in our suburbs by 1945. Similarly, the Tufted Titmouse population exploded there in the mid-1950s.

Of all the Florida specialties, I was most fascinated with the demure Limpkin, named for its halting gait, and famous for its haunting “mad widow” calls that pierced the night:

If ever I got to Florida, the Limpkin was the bird I most wanted to see. Highly specialized in its diet, the Limpkin subsists almost entirely upon Florida Apple Snails, which it can pluck from their shells in in 20 seconds. Its bill is specialized for the task, as it is compressed laterally like scissors, and its tongue is long, thin and barbed, the perfect tool for extracting the body of the snail.

Nearly extirpated from Florida 100 years ago by hunting and drainage of its habitat, the Limpkin’s population has recovered. Of greatest concern is the threat to the native apple snail by competition from introduced Channeled and Island Apple Snails, and by invasive exotic vegetation that replaces the snail’s food sources.

Mary Lou and I finally got to see our first Limpkin in August, 2002. Our daughter and her husband had just moved to Florida, and we were visiting them from New Mexico. Responsive to our desire to see a Limpkin, they drove us to Loxahatchee National Wildlife Refuge in west Palm Beach County. We all walked the trails, frantically searching for one, as the skies darkened and thunder boomed in the distance. Under the threat of the approaching thunderstorm, I retreated to the car ahead of them, but they continued their quest. Just as the rain started falling, they ran back to join me, calling excitedly that they had found a Limpkin!

Of course, I thought they were fooling me, and after the storm’s initial fury subsided a bit, my son-in-law convinced me that they had indeed seen the bird. Still suspicious, I accompanied him in the heavy rain to a ditch about a hundred yards away from the parking lot. Sure enough, there was a Limpkin, politely enduring the downpour as it awaited my return. That Limpkin was our first Florida life bird. In addition, we saw the endangered Snail Kite, which also is dependent upon Apple Snails as its food source.

These Apple Snail eggs were deposited on a suitable plant stalk at Long Key Natural Area in Davie, Florida:

Limpkins are quite common at Wakadohatchee Wetlands in Delray Beach…

…In Green Cay Wetlands in Boynton Beach…

…and at Shark Valley in Everglades National Park:

In March, 2008 I found this Limpkin, well camouflaged, on a nest in Loxahatchee NWR. Its mate was standing guard, and I did not approach very closely. Males are known to viciously attack any creature that gets too near, including humans:

Our most recent encounter with a Limpkin occurred one morning about two weeks ago while visiting nearby Chapel Trail Nature Preserve in Pembroke Pines, Florida.. We heard two Limpkins calling, one on each side of the boardwalk. To my ear, some of the Limpkin’s cries include rattling sounds somewhat similar to those of the Sandhill Crane, a related species.

Suddenly, one of the Limpkins flew up to the top of a small tree:

It then surprised us by flying in our general direction:

The Limpkin landed on the boardwalk railing and called again :

When I processed the photo, it provided a clear view of the Limpkin’s unusually long and slender tongue:

It then flew off in the direction of the second Limpkin:

Posted by: Ken @ 11:28 am

No visitor to South Florida who likes birds, or even has a marginal interest in the natural world should miss walking the boardwalk at Green Cay Wetlands, located in suburban Boynton Beach, just off Florida’s Turnpike in western Palm Beach County.

Mary Lou and I visited Green Cay the weekend before last, and were thrilled by the abundance of water birds. We arrived around 8:30 AM on a Sunday, and the large parking lot was already 3/4 full. Most of the visitors were older people decked out in exercise clothing. There were also many families with small children. I’ll admit that I did not relish the idea of joining such a large crowd, but as it turned out, they contributed greatly to our enjoyment. Except for the few power walkers who rushed through and brusquely pushed folks out of their way, everyone seemed to be having a fabulous time.

An Anhinga looked almost like a totem on a pole, silhouetted against the morning sun:

Soon after we entered, we were treated to the sight of a Limpkin perching 40-50 feet high, atop a bare Pond Cypress. We had never before seen one sit so high up:

A Northern Harrier with an owl-like face and a full crop eyed me as it flew over:

In an earlier blog (White Waders 3, Herps 0) I posted shots that I had taken at Green Cay, of an ibis subduing a water snake that it had caught, and an egret eating a Green Anole. All I had to do was point my long lens somewhere, and a small crowd gathered immediately, trying to see what I was watching. It reminded me of the traffic jams at Yellowstone National Park that could be started by anyone who pulled an RV off the road and began staring out into the distance.

Passers-by usually expressed a genuine interest in learning the identity of the many birds– herons, ibises, Limpkins, ducks, hawks, grebes, moorhens… They asked about what they ate, whether they nested there and where and when.

The smaller brown birds, such as this Sora, interested them a bit less, but stimulated comments that begged for my intervention, such as: “Look– it’s some kind of pigeon…”

…or, upon seeing this fuzzy-looking Pied-billed Grebe up close,”Look at the cute little baby duck!”

It was very difficult to show people this Wilson’s Snipe on a small island across the water, as it often blended into the vegetation before my very eyes, and when they saw it, most wondered why we bothered to look at it:

A big attraction was this large alligator basking on another island:

Unfortunately, Mary Lou missed the best show, as she had walked on ahead of me as we were exiting the wetlands. Out of the corner of my eye, I saw what looked like a fish being held up on a stick like a flag.

It was a fish, alright, but the “stick” was the neck of an Anhinga:

I raised my camera and took a series of photos, all the while answering questions from the crowd of people that quickly gathered to watch the show. I pointed out the the fish had actually been speared by the long sharp bill of the Anhinga, and that the bird would likely go to the shore before trying to subdue the fish before eating it.

The Anhinga complied by swimming to a half-submerged log, and displacing several turtles that had been sunning there. Strands of algae and duckweed clung to her back as she clambered up on the log with the fish firmly in her grasp:

Showing no mercy, the Anhinga began pounding the fish’s head on the log:

The fish struggled vigorously at first, shaking water drops all around, until it appeared to lose much of its fight. At this point, the Anhinga flipped it up into the air, intending to catch it headfirst before swallowing it. The fish had other ideas, and it slipped from the bird’s grasp as it tried to catch it coming down.

The Anhinga promptly disappeared under water and, within a few seconds returned with its prize, now speared near its head and looking badly battered:

Finally, the Anhinga sensed that it was safe to flip the fish up in the air one last time:

The Anhinga caught the fish head first, and people in the crowd exclaimed in disbelief that such a large fish could ever fit down the bird’s throat:

For a long moment it appeared that the fish had stuck in its throat, and the bird would choke to death:

Gradually, the fish slithered out of sight:

The show got even more exciting as the spectators watched the bird’s neck expand to accommodate its meal:

There was a round of applause as the Anhinga completed its act: