Posted by: Ken @ 8:52 pm

This past week, it may have been just a coincidence, but a cormorant and a stork were feeding quite close to each other at the corner of our lake, in the yard next door.

Double-crested Cormorant:

It is possible that both birds derived mutual benefit, as the stork might have caused larger fish to move away from the shore into deeper waters where the cormorant (a sight feeder) could more easily catch them. The stork might benefit because smaller fish may have been driven closer to where the stork (a tactile feeder) could clamp its jaws when they came into contact with its beak. Note also how the stork stirs the water with one foot while holding its wing up to shade the water around its bill. Its “bubble-gum pink” feet may also resemble worms to attract the fish. As I have discussed in earlier posts, the water level is critical to the success of the stork’s feeding technique. It must be at least halfway up its bill, but cannot be deeper than its eyes.

Wood Stork:

Small fish are believed to seek shelter in the shade. Herons are sight feeders, and some (such as the Tricolored Heron and the Reddish Egret) commonly use this same tactic, in order to cut down on reflection and also possibly concentrate prey in the shadow of its wings. (DISCLAIMER– I had to edit out a beer can that occupied the bank just in front of the stork’s bill.)

Here are examples of a Tricolored Heron and also an immature Reddish Egret using their wings to shade the water in front of them:

The Reddish Egret even created an “umbrella” that completely shaded its body:

Earlier this year, I documented the varied reptilian fare of a stork, an ibis and a Great Egret (see: White Waders 3, Herps 0). I observed a stork as it captured a frog– to me, it appeared to actually strike out and grab the amphibian, but perhaps its bill encountered the frog randomly and its capture was a reflex action. In this case, the stork was hunting alongside a Great Egret. White Ibises, also tactile feeders, are not as sensitive to water levels. Here, they are probing in the moist soil in our lawn at the lake’s edge. I have seen them chase down snakes, lizards and insects, so they can use vision in acquiring prey.

Ibises often forage in groups, and this likely improves their hunting success:

You may be interested in my post Sharing the Table: Commensalism. In ecology, commensalism is a class of relationship between two organisms where one organism benefits but the other is unaffected. There are three other types of association: mutualism (where both organisms benefit), competition (where both organisms are harmed), and parasitism (one organism benefits and the other one is harmed).

Commensalism derives from the English word commensal, meaning “sharing of food” in human social interaction, which in turn derives from the Latin cum mensa, meaning “sharing a table”. Originally, the term was used to describe the use of waste food by second animals, like the carcass eaters (such as vultures and hyenas) that follow hunting animals but wait until the latter have finished their meal.

Next to Chapel Trail Nature Center near our Florida home, Cattle Egrets cluster around cattle, reaping the benefits of their association as the bovines attract insects and also stir them up as they feed:

Also in our back yard lake, a Great Egret and a Wood Stork mutually benefited as another Double-crested Cormorant fished just offshore. Fish, frightened by the activities of the cormorant, fled in all directions. They blundered into the waiting open jaws of the stork as the tactile feeder waited blindly until sensing the hapless fish that bumped into its bill:

Three years ago I described the behavior of this Tricolored Heron, that associated with a group of Red-breasted Mergansers. All moved around the perimeter of our lake. Sometimes the heron seemed to be following the mergansers, but at other times the heron appeared to attract them by finding fish first.

Posted by: Ken @ 9:54 pm

The path that leads to to our favorite birding patch is only a few paces outside the entrance gate to our subdivision. However, we must reach the gate by walking in front of about two blocks of residences. Clothed in our rugged garb, we accept quizzical stares from passing motorists as they bring their kids to school or head for the office, all dressed up. We are often recognized as birders, and have acquired some legitimacy by answering questions from neighbors, such as “Did you notice that a lot of baby white cranes [translation: Snowy Egrets] have just joined their parents [translation: Great Egrets] along our lake?”

Here in Florida we must pay special attention to protection from sun and insects. Sensible wide-brimmed hats, trousers tucked into socks and long sleeves on the hottest of mornings make us stand apart on the fashion scene. (No wonder Mary Lou regarded all birders as rather eccentric folk– until she became one herself! See: “A Valentine for my Favorite Birdwatcher“)

The latest additions to my wardrobe and gear have been an insect-repelling shirt, waterproof snake-resistant boots and an OP/TECH Dual camera/binocular harness. Here I am, all decked out and ready for action (photo courtesy of Mary Lou):

The harness has solved a vexing problem. Until now I have been carrying my camera and binoculars, slung over my neck and opposite shoulders. This can be a troublesome arrangement, Not only do the straps conflict with each other, pinching and constricting my neck all around, but their business ends can become hopelessly entangled. It’s very disconcerting to lift the camera for a shot and find the binocular strap wrapped around the long lens. The harness (or halter) stores the two items of equipment independently on each side, and distributes their weight on a single soft neoprene yoke that goes over both shoulders and is secured by a chest strap. Strangulation is out of the question.

Well, the snake boots are something else. A few close encounters with Cottonmouth water moccasins notwithstanding, I am usually very careful about looking where I step, and am not afraid of any snakes– provided I see them first. My attitude changed a couple of months ago, when (wearing sneakers) I went out in the pre-dawn darkness to try to obtain a photo of one of the Bobcats that live in the wetlands. I forgot to take a flashlight, and depended upon the moon and a little keychain LED lamp to light my way. This was fine until I had to cross some deeper grass and felt that I might be taking my life into my hands. Indeed, another photographer who walked out that way a couple of mornings earlier (and obtained a knock-out Bobcat portrait) told me he saw four small moccassins along the same path. Why didn’t I see any? This experience, and prodding from my spouse, son-in-law and daughter (as well as a couple of birding friends) led me to finally buy the snake boots.

This past Friday, we got out about ten minutes before sunrise and took our usual warm-up “power walk” to the Harbour Lakes Impoundment, a lake about a mile away from our gate. Here, a day-old full moon hovers overhead and the first rays of sunlight have just reached the trees on the far side of the lake:

An Osprey flew over, the early rays illuminating its flight feathers from below:

Along the way, I stopped to photograph a Common Ground Dove…

Truth be told, I just don’t take one picture and move along. Usually, I shoot as soon as I spot my subject, then move in cautiously for better views. Rather than shoot in bursts, I like to catch the bird doing something, such as calling, preening, or looking up, down or over its back. Such poses seem more interesting than simple “field guide” side-on views. If a twig or leaf is in the way, or part of the bird is in shadow, I try to angle around it or wait until the bird moves into a more suitable location. Approaching nearer to the subject requires stealth and slow movements. Each bird seems to have a limit as to how closely it may be approached. (The shrike usually flies off if someone gets within about 30 feet, though there are exceptions). All this takes time and can be very BORING to a non-photographer birding companion. I know this from experience, having taken up photography only recently, and used to hate it when photographers held up other birders’ progress.

Therefore, Mary Lou usually leaves me with my camera and starts birding her way back home within an hour, alone– that’s her, fading away in the distance:

Look closely at the above photo. she is just passing the small, compact wooded area that I call my “fake hammock.” Although it is an isolated area of hardwoods and is dry underfoot all year long, it otherwise bears no resemblance to a “real” hammock, an elevated island in the Everglades, populated by native oaks, mahogany, maples and palms. While my fake hammock contains ligustrum, exotic Brazilian Pepper and lantana, it also has several large native Florida Trema trees (Trema micranthum) with an endless crop of nutritious berries that continue to ripen all winter. These trees are very attractive to wildlife. Visit “Birding in a make-believe hammock”

Trema berries grow along the stems of the tree and are in various stages of ripening:

I had not entered my “hammock” since spring, and found the path that led into it overgrown with high weeds, vines and shrubs. I would never have ventured there without my new snake boots, but I forced my way under the canopy of the trees. Once inside, I found very little ground cover in the rather open shaded area.

An old folding chair had been left there a long time ago and it provided a nice place to sit and just wait for the migrating birds:

I did not have to wait very long, as two vireos suddenly showed up to partake of the Trema berries. One had markings that suggested it might be a Black-whiskered Vireo, but other views confirmed it was a common Red-eyed Vireo with “bad hair”(click on photo to also see a Black-whiskered specimen that I photographed at about the same spot in March of this year:

No doubt about it– they were indeed Red-eyed Vireos:

These were the best open shots I’ve ever gotten of the usually secretive species:

Just above my head, a male Prairie Warbler foraged in a sunny patch of leaves:

A noisy group of three Red-bellied Woodpeckers flew in, allowing me to pull off a couple of lucky shots before they disappeared:

There were very few mosquitoes and no deer flies, and it was almost cool inside my hiding place, as I watched a Black-and-White Warbler work its way towards my position (click on image for more views):

OK, I OD’d on Black-and-Whites. I probably took over 100 shots, almost all through peep-holes between the branches, and most marred by the rapid movement of this little sprite. Then it came into the open and I finally got some full views:

A Northern Parula peered down at me from the canopy:

Another brightly colored male Parula joined him:

The Blue Jays have completed their molt, and this one looked sleek and handsome:

Blue-gray Gnatcatchers were almost as distracting as the many butterflies that fluttered in my peripheral vision:

A Brown Thrasher was a surprise visitor:

This Great Crested Flycatcher preferred to perch against the sun and sky, providing me with only severely back-lighted soft images:

For me, the real treat was a pair of Ovenbirds that chased each other back and forth, rarely sitting still long enough for decent portraits; this one insisted on hiding behind a leaf as it eyed me:

The other Ovenbird never perched nearby, requiring me to shoot through holes in the foliage into its shaded retreat:

This tailed butterfly is a Dorantes Skipper:

Posted by: Ken @ 8:39 pm

Returning from Illinois this past Thursday, our aircraft passed eastward over the Fort Lauderdale airport and took a long downwind leg over the ocean. This meant that the wind was blowing in from the Everglades, and we could expect rising temperatures and a plague of mosquitoes until the easterly sea breezes returned.

The unsettled air produced a lovely sunrise, but bad as the mosquitoes, heat and humidity have been, other concerns are keeping us from going afield:

When we opened our front door upon arriving from the airport, we were greeted with the stench of rotting fish. At some time early in our 6 weeks of visiting Illinois and cruising the western Mediterranean, my 55 gallon glass aquarium had developed a pinhole leak about halfway up. A corresponding amount of water (along with an additional 8 gallons in a reserve tank that maintains the water level when we are away) had flowed to the floor. The filtration system became inoperative, and the water turned stagnant. All five of my big Koi died from oxygen deprivation. They were in advanced stages of decomposition. Not a nice welcome!

I quickly disposed of the dead bodies, but it was too late in the day to do much more. Luckily, our floor is travertine marble, and the aquarium is located next to a sliding glass door, so the water mostly flowed directly outside under the metal door frame. The cabinet under the tank was badly stained, and I have spent much of past three days cleaning and repairing the tank, and refinishing the cabinet.

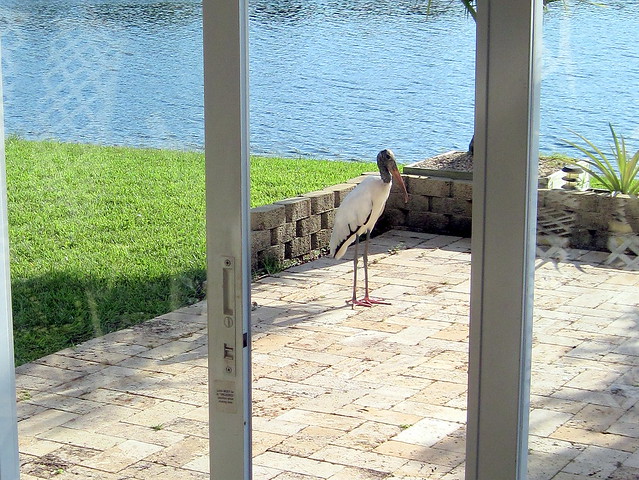

Six weeks ago, just before we departed for Illinois, we had an interesting visitor on our back patio. It was an adult Wood Stork, the first we had seen this summer. The storks have had two consecutive unsuccessful breeding seasons in the southern Everglades. Water levels must be nearly perfect before they will begin nesting. Water must be deep enough to protect them from terrestrial predators. Yet, since the storks are tactile feeders, the water must be shallow enough to concentrate their own prey. Water deeper than about a foot causes them to abandon their nest area to forage far and wide, and there is danger that their unprotected young may starve or be killed. Most summers, we have had family groups of adult and immature storks.

I took this photo through the open patio door:

The stork was unusually tame, and it walked right up to our patio window. Though it appeared otherwise healthy, we were concerned that it might be ill or impaired:

This afternoon I looked out the back window and found a Great Blue Heron resting on our patio wall. It was standing in full sun and the heat-stressed bird exhibited intense gular flutter (rapid pulsation of the throat, a cooling measure). I could not fit the entire bird in my telephoto lens, as it was only 20 feet from the window, so I had to use my point-and-shoot Canon PowerShot A 1100 IS for full-body shots.

I backed away from the window and got head and neck images with

the 420mm lens system. Taken through the window glass, both shots are a bit soft

We do not put out feeders, as the Muscovy Ducks and Rock Pigeons overwhelm them. Our lake itself is a big “bird feeder,” and so are our patio, lawn and trees. When we can’t get out, we wait for the birds to visit us.

Blue Jays nest in our back yard mahogany tree:

A Yellow-crowned Night-Heron forages on our lawn for insects, earthworms and lizards:

Killdeers probe the water’s edge:

A Little Blue Heron chases after lizards and geckos on our patio:

Cattle Egrets generally stay away from the water, but sometimes stop by:

A stealthy Green Heron sits in a flower pot:

The heron,alarmed by my presence, raises its shaggy crown:

A single dead fish may attract several Turkey Vultures:

Ospreys fly overhead:

A Double-crested Cormorant rests on a decoy that serves as a float for a lawn irrigation intake. The goose’s sculpted plumage mimics that of it passenger :

Soon, Palm Warblers will return for the winter::

This Loggerhead Shrike is hunting for anoles in the impatiens:

A Muscovy Duck walks her brood across our patio:

This Green Iguana enjoys munching on our flowers:

Alas, we are leaving our second home in northeastern Illinois to return to Florida, just at the start of warbler migration. Yesterday Kane County Audubon Society sponsored its monthly “Scope Day” at Nelson Lake/Dick Young Forest Preserve, only about a mile from our condo. Although I obtained not a single decent shot of any of the Common Yellowthroats, American Redstarts, Magnolia Warblers and Black-throated Green Warblers we sighted, the arduous 3 1/2 mile walk around the lake made for a most enjoyable morning. We logged over 60 species.

The group included a nice mix of experienced and casual local birders, as well as visitors from out of state. They gathered on the east viewing platform to scope out herons and ducks:

Here, some of the two dozen birders who showed up are zeroing in on a Sedge Wren that posed nicely in the tall grass (until I raised my camera):

The past three days have been hotter and more humid than back “home” in Florida. The day before “Scope Day” I braved the heat and scouted out the east side of Nelson Lake. There were relatively few migratory birds to be seen after about 8:30 AM. They probably were hiding in the cool shade

This Magnolia Warbler was a sweet find, though its photo is a bit out of focus:

As usual, an American Redstart made my job very difficult by refusing to sit in one spot for more than a nanosecond:

When migrants are few and far between, I can always turn to more familiar subjects, such as this Black-capped Chickadee:

Common as they may be, I have found it difficult to get decent shots of chickadees; here is one from a different perspective:

A Ruby-throated Hummingbird appeared briefly in my viewfinder:

A couple of days earlier I serendipitously obtained a better image when a hummer wandered into my field of view as I was photographing a flock of Tennessee Warblers at Les Arends Forest Preserve; note its long tongue:

This redstart eyed me briefly:

The Tennessee Warblers were nearly as uncooperative as the redstart had been. Here was my best shot of one, peering out from under a leaf:

The best I could obtain from this Nashville Warbler was a “butt shot,” which nicely illustrates the yellow undetail coverts and longer tail feathers that help distinguish it from the more numerous Tennessee Warblers when they mingle in the treetops:

Three of the flycatchers that I spotted the day before before Scope Day failed to show up for the wider audience. This is a Least Flycatcher…

… a shadow-marred Great Crested Flycatcher…

… and here is my fuzzy shot that documents my sighting of an Olive-sided Flycatcher:

Exactly one year earlier, I had captured a better view of the Olive-sided Flyactcher at the same location, one that exhibits its namesake dark “vest:”

White feathers may ruffle up on the rump of this species, providing another useful field mark:

Compensating for the absence of their flycatcher cousins, Scope Day participant saw many Eastern Wood-Pewees:

American Goldfinches were the most common land birds we saw on Scope Day:

The goldfinches were busy attending to their young. Earlier this week, at Lippold Park, I captured this female gathering thistles for her nest:

Unlike nearly all other songbirds, goldfinches do not feed insects to their young. Instead, the adults ingest seeds and regurgitate a protein-rich “milk” from their crop linings:

Audubon walks are not only about birds, and participants got to see some interesting insects, including this Praying Mantis…

…a close-up of a nectar-sipping Eastern Tiger Swallowtail…

…a pollen-gathering Carpenter Bee (told from a Bumblebee by its dark non-furry abdomen)…

…and a vivid male Common Whitetail dragonfly resting trailside:

Finally, as I arrived home, hot and dehydrated, I saw the family of Sandhill Cranes resting in the shade of a willow next to our condo; my presence put them on alert: