Posted by: Ken @ 11:07 am

Now that I have become the proud owner of a pair of snake boots, I took up my neighbor Scott’s open invitation to accompany him on a deeper hike into the wetlands adjacent to our homes. This area, located just west of the cities of Miramar and Pembroke Pines, is part of the Broward County Water Preserve, consisting mostly of land that has been set aside by developers to compensate for intrusion upon the historic Everglades by construction of housing subdivisions.

Much of this is land that long ago had been drained and converted to agricultural use, mainly grazing of livestock. Now it is partially surrounded by low levees and managed by the South Florida Water Management District (SFWMD) under supervision of the US Army Corps of Engineers. As part of the Comprehensive Everglades Restoration Plan (CERP), the land was more recently cleared of invasive exotic plants, notably Melaleuca, Australian Pine and Brazilian Pepper. In the portion nearest our home, maintenance appears to have ceased since about 2005, and the exotic Melaleucas are once again spreading into the open wetlands, where they form dense stands.

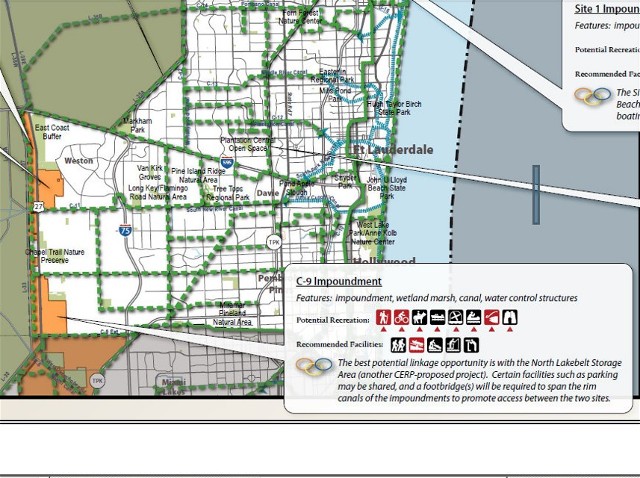

Under CERP, this wetland will be surrounded by higher levees and turned into a huge reservoir to hold storm water overflow from the planned C-11 impoundment to be constructed ten miles to the north, in Weston. The water depths in this planned lake will vary, depending upon rainfall, from zero to four or perhaps six feet. The objective of this impoundment is to limit eastward seepage of Everglades drainage, thus recharging the aquifer and reinforcing the historic north to south flow of the “River of Grass.” Because of funding and logistical issues, construction of the C-11 impoundment would not begin until at least 2015.

Therefore, our local reservoir (designated as the C-9 impoundment) is on hold for at least ten years. From our standpoint, this is good news, as we now enjoy the presence of terrestrial species that will certainly be driven out when the area is flooded. Here is an informative link about CERP, which includes the following map:

Water levels in our disturbed local wetlands weakly imitate the natural cycle of the original Everglades. An extinct quarry forms a large lake that occupies much of the Harbour Lakes portion of the preserve. Summer rains swell the lake and it spills over into the surrounding Sawgrass meadows. Sawgrass is actually a sedge, and it thrives when the soil is waterlogged for ten to twelve months out of the year.

Water now covers the adjacent Sawgrass meadow. The waterway in the foreground will be a dry to muddy trail by late spring or early summer, but is too deeply submerged for our morning jaunt:

Some parts of the wetland are better drained or are at slightly higher elevations, so their shorter hydroperiod (the length of time that there is standing water) favors beds of periphyton*, algae and other plants such as Spike Rush.

*From: Freshwater Marl Prairie

A complex mixture of algae, bacteria, microbes, and detritus that is attached to submerged surfaces, periphyton serves as an important food source for invertebrates, tadpoles, and some fish. Periphyton is conspicuous and is the basis for the marl soils present. The marl allows slow seepage of the water but not rapid drainage. Though the sawgrass is not as tall and the water is not as deep, freshwater marl prairies look a lot like freshwater sloughs.

A Great Egret stands in this marl prairie, which is covered mostly by rushes:

In January, periphyton floats to the surface as the water level recedes:

The areas free of Sawgrass are richer in nutrients and more friendly for wildlife, such as this American Bittern hiding among the Spike Rushes:

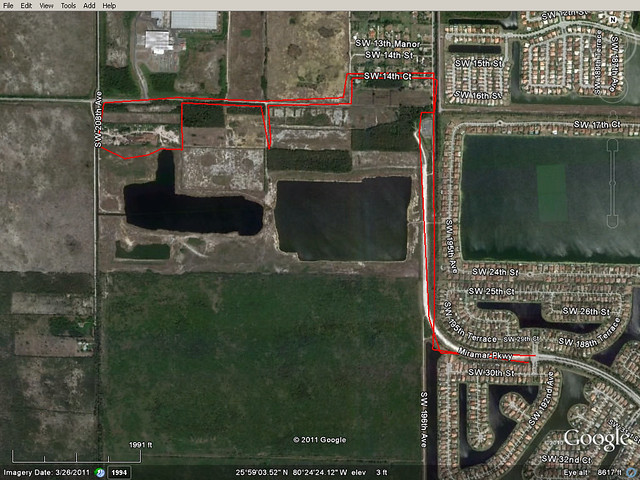

Scott is a “working stiff,” so we met up at 7:30 AM on Saturday. To my surprise he had his little Yorkie, Gordo, on a leash. Gordo was to prove to be a enthusiastic and even useful companion for what turned out to be an ambitious five mile hike. We walked a loop north into Pembroke Pines on the unpaved Miramar Parkway/SW 196th Avenue extension, then cut south and west almost to US-27. At times we found ourselves in water up to mid-shins and sunk into ankle-deep mud. We departed at 7:30 AM and got back around 11:00 AM.

This was our route, beginning and ending at the lower right (SE) corner of the map:

We walked mostly on remnants of old farm roads, which are blocked from vehicular traffic, but often used by recreational ATVs. The cross-country part of our walk was the southern portion of the loop in the upper left part of the map. There, we made very slow progress through a flooded prairie of Sawgrass. We followed animal trails (presumably deer) that tended to make circuits around deeper sloughs and alkali sink holes, but the going got so tough that we considered turning around when we had bushwhacked more than half way to our goal, which was the unpaved portion of SW 208th Avenue that runs north and south (along the far left side of the map). All this time I kept my camera safely tucked away.

As we approached the road we heard dogs barking in the junk yard to the north, and when we finally emerged into the open we were greeted by a pack of eight to ten mixed breed hounds. Thankfully, they were more interested in Gordo, who diverted their attention as we made friendly talk with them and tried to act nonchalant.

Before the dogs actually reached us we encountered a young Cottonmouth in the two-track road (note its bright coloration and yellow tail; older moccasins turn dark with obscured markings) :

I wondered how many snakes we had NOT seen during that part of the hike, and was really happy with my snake boots– except that it turned out that both boots leaked! The walk back was a bit squishy.

A Red-bellied Woodpecker clung to an old telephone pole:

Along the way, a Red-shouldered Hawk monitored our approach before flying off:

Gordo found this pugnacious crayfish along the path. It attacked him, then me as I tried to catch it. They are known to change colors, and perhaps the red reflects its fighting mood (I took it home and it now resides in my aquarium– dull olive brown in color):

Scott and Gordo on this trail, which follows the right of way for Pembroke Road:

Two Painted Buntings flew along the trail in front of us. I only was able to photograph the female, and she was a beauty:

One of a pair of Northern Waterthrushes created a very pretty reflection in a puddle:

Two Yellow-crowned Night-Herons were roosting at the site of last year’s rookery:

Not to be overlooked were this roadside Loggerhead Shrike…

…a White Peacock…

…and a Gulf Fritillary:

By the way, I sent the boots back to the manufacturer, as they were guaranteed 100% waterproof. They have already shipped out a replacement pair. Since they fit well and were quite comfortable (when dry) I will assume my problem represented a sample defect and will withhold any review of the product pending resolution of the issue.

Posted by: Ken @ 9:34 am

Before we left Illinois early in September, we had been experiencing heat and humidity that rivaled that in our Florida home. As soon as we got back to Florida, Illinois cooled off, but Florida seemed hotter than ever. With the arrival of autumn, heat and morning rain showers have reduced our time in the field.

At the same time, we have been more alert to happenings at the home front– particularly on the lake in back of our home, where an interesting drama played out. I noticed that a Double-crested Cormorant had caught a large exotic Plecostomus species. The 9-10 inch fish is native to the Amazon and popular in the pet trade, and has invaded south Florida waters. It struggled vigorously in the bird’s beak, its spiny fins fully extended. I do not know how long the fish had been in the cormorant’s grasp, but I watched intently to see if the bird could succeed in swallowing it, or whether it might get stuck in its gullet.

These photos cover a period of about 7 minutes. The bird won!

Cormorant takes on a Plecostomus (to see how the battle ended, CLICK HERE for a slide show):

Dodging a few raindrops, we did get out a couple of mornings this past week. Our first walk was the usual visit to the water conservation preserve next to our subdivision that we call the West Miramar Environmentally Sensitive Land (ESL). The sky overhead looked fine, but there were ominous clouds over the Everglades to the west.

At dawn, we entered the unpaved road that leads westward into the wetlands, and were greeted with this view:

We walked quickly at first, but stopped to look at a couple of roadside attractions.

A Loggerhead Shrike defecated just as I clicked the shutter:

This Eastern Kingbird looked atypical. It assumed a vertical elongated posture, unlike their usual more horizontal hunched attitude. Also, the terminal white band was almost invisible on its worn tail:

Mary Lou alerted me to the approach of a Red-shouldered Hawk, and I got the camera up just in time as it flew almost overhead:

We found the water level to be very high in the Harbour Lakes impoundment. The lake had flooded into the adjacent grasslands, and the mud flats had disappeared under a foot or two of water. We continued our “power walk,” but now moved more slowly as the sun rose higher and the sky turned blue.

This distant Great Egret was all alone on the lake:

We continued to the end of the road, and started walking the mile back to home. On the way, I tarried in the area of the “fake hammock,” and Mary Lou continued home without me. Again, I had to break through high grass, vines and tree branches that had proliferated at the edge of the woody patch.

As usual, the open space inside the “hammock” was shady and inviting:

An Ovenbird appeared in the open area and flew to a low perch:

The Ovenbird posed for almost a minute as I feverishly clicked off photos:

Several Florida Trema trees were producing berries in clusters along their stems. The fruit continues to ripen through the winter, and attracts insects and many migrating and resident birds, such as this Northern Cardinal:

No less attractive, his mate was also partaking of the crop:

Against the sky, the iridescence of this Common Grackle was uncommonly beautiful:

A Red-bellied Woodpecker displaced the grackle on the perch:

Blue-gray Gnatcatchers had migrated in, and many will stay for the winter:

So far, we have not experienced a huge invasion of migrating warblers, but this female Black-throated Blue Warbler was a welcome visitor to a Trema tree:

This was the best shot I could get of the male Black-throated Blue Warbler, as he never came out into the open:

A female American Redstart, one of several I saw that morning, was unusually cooperative, striking a pose before dashing off after insects:

A male redstart was even more difficult to capture as it moved through the Trema branches:

Intent on my photography, I failed to notice that the skies had turned darker and a breeze began building. Too late for a retreat, I hunkered down in the most densely covered area as big drops started to fall. Lacking a camera bag or any rainproof clothing, I had to shield the camera with my body during what turned out to be only a brief downpour. Mental note– bring garbage bags out next time!

Photos came out soft in the mostly overcast skies. This is one of several Eastern Wood-Pewees I saw after the shower:

Another flycatcher showed up and it looked different. It seemed smaller than a Wood-Pewee, and and its eye ring was complete and more pronounced. It constantly flicked its tail downward, which would be unusual in a pewee. On close examination it appears to have shorter wings and shorter primary projection than a pewee, and its under-tail coverts are clear rather than smudged as with the Eastern Wood-Pewee.

It did not vocalize. I believe this is a Willow or Alder Flycatcher, reliably distinguished only by their calls (”Traill’s” complex):

During lulls in birding, I paused to enjoy the insects, like this Zebra Heliconian:

I could not identify this tiny skipper, probably a member of the Grass-Skipper group:

This Giant Swallowtail is at the other end of the size spectrum:

Before the rains came, I got this nice shot of a garden spider and her handiwork:

Posted by: Ken @ 3:59 pm

Last week, while I was still in Illinois, I received an e-mail from Michael Fullana, a professional photographer who lives near our Florida home. He had seen one of my Bobcat photos on the Internet and was surprised to learn that they could be found so nearby. I gave him detailed instructions and within a day or so he was out before dawn in the wetlands next to our subdivision. He was able to get two photos of a very handsome Bobcat a little after sunrise.

Bobcat (c) by Michael Fullana:

Creative Edge Photo www.creativeedgephoto.com Used with permission

Obviously, Michael’s photo was to die for, so I planned to get out early myself on the first morning that we did not have medical and dental appointments. Today we finally had no other obligations or early rain.

It was pitch black and there were no clouds when I left the house at about 5:20 AM, slathered with mosquito repellant. Away from the street lights, I walked along the unpaved roadway with a bright half-moon directly overhead. When I got to the spot where I usually cross over a berm into the protected area near the 196th Avenue Canal, I hesitated because it looked unfamiliar. The grass had grown quite high since my last visit over six weeks ago, and I have seen Cottonmouth moccasins here. It was just too dark. I had a little LED light on my key chain, so I used it to illuminate each step until I got on the open path where the moonlight revealed much more detail. It was too dark for me to proceed south on the trail along the levee where Michael had noted many Marsh Rabbits, a favored prey for Bobcats.This morning there were no rabbits to be seen– a bad sign? I tried to test fire my camera and there simply was not enough light.

Distant lightning flickered from a storm over the Florida Keys.As I waited in the dark, I noted the sounds around me, over the drone of mosquitoes. Tree frogs and geckos chirped like little birds. Purple Martins calls drifted down from the black sky. Night-herons squawked in the darkness. The first bird song I heard was the “Drink Your Tea” of an Eastern Towhee. Cardinals soon followed, along with one Carolina Wren. Mockingbirds were strangely silent. Boat-tailed and Common Grackles added their poor excuses for songs, along with a few Mourning and White-winged Doves.

In summer, here in the sub-Tropics, as Kipling said, “dawn comes up like thunder.” With the first bare glimmer of red in the east I attempted more test shots at various settings, but the shutter would not click.The sky rapidly lit up, and by about 5:50 AM I could get grainy exposures at ISO 3200, so I started walking slowly along the levee path. Mike said he got his photo at around sunrise, which was at 6:42 AM. I walked the quarter of a mile to the spot where he (and I, on several previous occasions) had seen the Bobcat. By then I could reduce the ISO to 1000 and take decent flash shots, pointing away from the path. My chosen vantage point was just off the main trail with my back to the east. One step forward permitted me to look both ways up and down the levee trail, which runs north and south. Directly in front of me, a side trail, already partially under water, led westward, deep into the wetlands. I waited, cautiously peeking from side to side every few seconds.

Suddenly, at about 6:20AM, I saw what I thought was a deer grazing at the edge of the path to the south. Forgetting that the flash was still on, I raised the camera and popped off a shot:

The animal immediately looked up and I realized it was not a deer:

When I checked the photos on the camera’s LCD display I saw the eye shine and realized the gravity of my error. The cat stayed in place for a few more seconds, and I took several photos without the flash:

The above was the best of a batch of poor exposures. Because of the low light, there was considerable camera shake at ISO 1000. Worse, I auto-focused on some branches in front of the Bobcat. My manual focus shots were no better in the poor light. Vision problems with my right eye have limited my ability to focus sharply, and I just cannot get used to shooting with my left eye, as the camera is not friendly that way. Well, I will certainly try again, but not get out quite so early, and also will be extra careful about using auto-focus!

On the walk back along the path, I stopped to photograph this male Queen butterfly:

A small bird flitted right across my field of view just as I depressed the shutter. It was a Carolina Wren, elusive as usual:

Nearby, a Loggerhead Shrike was surveying its territory from atop a Melaleuca tree:

A female Prairie Warbler was carrying an insect, almost certainly to feed a nearby nestling or fledgling:

Prairie Warblers breed locally, and are one of the few warblers we get to see during the summer. After moving back and forth between trees with the insect in her mouth, she ate it, perhaps to help conceal the presence of its young. I have seen such behavior before in other species, though it would be hard to prove its motivation:

Before heading home, I turned north on the unpaved stretch of Miramar Parkway/SW 196th Avenue and visited the Harbour Lakes impoundment portion of the wetlands preserve that I call the West Miramar Environmentally Sensitive Land (ESL).

The reflection of a Great Egret highlighted the still water along the opposite shore:

A Red-winged Blackbird sang “Conk-ra-lee!” at the edge of the lake:

This Florida Box Turtle was crossing the gravel road while the sun was getting higher and hotter. As I approached I heard him hiss when he saw me: “(Oh) Shhhhhhi…t!” He tucked in his head and legs and looked out only after several minutes had passed:

He might be slow, but his eyes sparkled with life:

After I took these photos I carried the turtle over to the shade of a grass clump on the side of the road. I turned away and within seconds he was actually running to the safety of the deep grass further back from the road!

Posted by: Ken @ 5:47 am

Readers have probably noticed that I take most of my photos in birding “patches” very close to home, mainly in the adjacent water conservation area that we call the West Miramar ESL (for its designation by the South Florida Water Management District as an environmentally sensitive land or area). Rather than chase after rarities, we usually wait for the birds to visit us. Pretty soon we will respond to our own migratory urge and try to catch up with them up north.

We enjoy the birds, but we also like being in the places where the birds are– mostly scarred remnants of former natural beauty, but places where we can briefly ignore the sounds of lawn mowers and leaf blowers and hear splashing on the lake and the songs of cardinals, yellowthroats and towhees. We like getting out early, around sunrise, and walking fast before stopping to watch and listen.

On the first of January this year I reflected on the fact that now I have lived a portion of my life in each of the past nine decades. This does not make me 90 years old, but it means that I was born in the middle of the Great Depression and accounts for my compulsion to get up and out and make the most of every day.

Depending upon the birds to come to us creates a sense of urgency during migration. We must be out there to greet them. Earlier this week we learned we could not predict the arrival of flocks of warblers in our neighborhood. Trying to anticipate the perfect morning for birding during migration, I keep track of the weather radar. So far there has been little correlation between the abundance of migrants in our neighborhood and the density of the flocks that appear on the radar screen.

For example, on April 14 we saw nine warbler species, as reported in our previous blog. That night the radar looked very promising. It appeared that migrating birds had piled up on the northern coast of Cuba and had begun their flight across the Straits to Florida at sunset. We hoped that the next morning would be even better for warblers.

Here is the Key West radar image covering the period between 9:30 and 10:38 PM EDT on April 14th:

Angel and Mariel track migrants on radar in their blog, Badbirdz2. They reported “Heavy Migration Over Florida” and their overnight radar loops documented the continued passage of migrating flocks over south Florida, including our home, into the early morning hours. We got out early, expecting to be surrounded by colorful warblers. I hid inside the “hammock” for two hours, and saw many, many catbirds that may have helped cause the radar echoes, but not a single warbler, or other migrant!

Before Mary Lou abandoned me at the “make-believe hammock,” we had visited the lake at the far end of the unpaved road into our patch, where we found a small flock of Least Terns. A pair of Least Terns posed nicely on a rock:

They flew back and forth in front of us, allowing me to practice taking in-flight telephotos with my new Canon 60D:

The smallest of the terns, the Least Tern has a proportionally long bill and short tail, and in breeding plumage has a black cap and sharply contrasting white forehead:

I caught a Red-winged Blackbird in mid-song, his partly spread wings showing off bright red epaulets:

The light was behind this Tricolored Heron as it watched us warily:

A Green Heron joined the terns along the edge of the lake:

Two days earlier, I was so engrossed in photographing the terns that I forgot a cardinal rule– never take a step without first checking the surroundings. Out of the corner of my eye, I caught the slow movement of a snake, only about three feet away.

It was a poisonous Cottonmouth water moccasin:

Of course I stepped back as the snake coiled into a defensive posture. It opened its mouth and began to regurgitate what looked like the tail end of a siren (a common legless amphibian). This may have been in response to the stress created by my disturbance:

Like cats and other nocturnal predators, all the North American poisonous snakes (except for the Coral Snake) have elliptical pupils. This is an adaptation to night vision, allowing them to protect their sensitive eyes by shutting out almost all the light if necessary:

Snakes are fascinating creatures. Cottonmouths eat a great deal of carrion, and are not aggressive. They are inconspicuous, and about the only way to get bitten is to touch one or step on it unawares. As a sad footnote, when we returned to this spot we found a Cottonmouth, probably this same snake, crushed by boulders:

Yes, it is poisonous, and some guy now thinks he’s a hero, but I don’t think that the world is made any better by senseless killing.

As a kid, I used to step on any ant I saw on the sidewalk, for sport, or maybe to make it rain.

Such a habit may have persisted in my subconscious mind. Several years ago, while leading a group of 8 to 10 year old kids on a nature walk at Rio Grande Nature Center in Albuquerque, I casually stepped on an ant– I must admit it was an intentional act.

One of the kids immediately asked, “Why did you do that?”

“Do what?”

“Step on that ant.”

I could only reply, “It was wrong for me to do that– the ant was minding its own business and wasn’t doing anything to hurt me.”

Why did I do that? It was a simple but profound lesson for me. I had extinguished a tiny spark of consciousness, and my universe had been diminished, be it ever so slightly.

Posted by: Ken @ 12:28 pm

A bad cold has limited my time afield the past week. Feeling the need to attain Bird Chaser’s “Recommended Daily Allowance” (RDA) of 20 bird species, I ventured out on a 15 minute walk to the canal that borders our subdivision, and also serves as the eastern edge of the Broward Water Conservation Area. The WCA is a buffer area between the developed west edge of Broward County and the Everglades. I call the southeastern corner of the WCA the “West Miramar Environmentally Sensitive Land (ESL)“:

As I walked in on the gravel road, House Wrens and Common Yellowthroats scolded from the weeds on either side. Boat-tailed and Common Grackles flew overhead, Blue Jays called to each other in the dooryards, and doves cooed from rooftops: White-winged, Mourning and Eurasian Collard-Doves. Palm and Yellow-rumped warblers flitted in the Live Oaks and hedges. Ten species already. For an hour and a half, I remained within a small area of disturbed grassland and woodland along the canal, allowing the birds to come to me.

A male Northern Flicker sits atop the broken-off trunk of a dead Royal Palm:

Suddenly, a male American Kestrel displaces the flicker:

The kestrel flies to the top shoot of a distant live palm– he appears to be choking to death!

After several seconds of gagging, he dislodges a pellet, comprised of indigestible prey remains: feathers, hair, nails, insect exoskeletons and some bones:

There is no need to wander far and wide to enjoy little pockets of wild space. Resident White-eyed Vireos have now been joined by a larger number of migrant White-eyes from points north:

A Loggerhead Shrike is unusually tolerant of my close approach:

A flock of Cattle Egrets is joined by an immature White Ibis (dark wings) and a Snowy Egret (yellow feet):

A Male Belted Kingfisher stands watch over the canal next to our property:

He flies high over the water, hovers and then makes a steep dive:

The kingfisher catches a good-sized fish, takes it to a perch, subdues it by striking it against the branch several times, flips it and swallows it headfirst (click on the image to see sequence of photos):

On the opposite shore of the canal, a Great Blue Heron imitates a ballet dancer as it makes a graceful landing:

How can I pass up another Northern Cardinal photo-op, especially since it is the twentieth species for the day?:

Having attained my “RDA”, I looked up and almost ignored what I first thought was a female cardinal. On closer inspection the large bill belongs to a migrating female Summer Tanager:

In an adjacent exotic Melaleuca tree, a strongly marked male Prairie Warbler eyes me– 22 species!:

Suddenly two Northern Harriers appeared in the distance over the wetlands. Characteristically, they reached the near margin and turned around. Anticipating that they might continue to move back and forth, I positioned myself at a clear place on the levee, to get a better look should they reappear. Soon they came back into view. One was a large brown female, but the other was a smaller adult male. I have found males to be relatively scarce, and I have never obtained a decent photo of one. They were about 100 yards away when they turned and flew from my left to right side.

The male Northern Harrier is beautifully patterned in gray, black and white:

As my 23rd species moves away, he displays his signature white rump:

Turning my attention to the butterflies, I capture my first-ever image of a Giant Swallowtail:

Another first– a Long-tailed Skipper, with an iridescent blue-green body:

This

White Peacock rests in the cool shade. It is a particularly fine

specimen, as most have wings that are tattered by their frequent

territorial skirmishes::

A Zebra Heliconian, State Butterfly of Florida:

Nearby, a male Julia Heliconian:

The Scarlet Skimmer (Crocothemis servilia) is a dragonfly species native to Asia which was introduced to southern Florida. It was first discovered in the U.S. near Miami, Florida, in 1975 and since has become common across most of the southern half of the Florida peninsula:

Proud Grandfather talk–

Before I leave the subject of butterflies, I want to share a few photos our daughter just sent us from Illinois. While we were back there about 6 weeks ago, our 6 year old granddaughter found a Black Swallowtail caterpillar on the sidewalk in front of their home. The budding naturalist proudly brought it to me and announced she was going to save it and watch it turn into a butterfly.

She did this the first time when only three years old. Here is a 2007 photo of the girls with an emerging Black Swallowtail. Read the full story : Goodbye, Butterfly)

She already knew that this species eats parsley and other plants in the carrot family, so she found some Queen Anne’s lace stalks and put them into a plastic storage container with the caterpillar. In only about three days, the caterpillar lost its skin and turned into a chrysalis. She asked if I knew how long it would be before the butterfly emerged. I told her that this late in the season they normally would not come out until the next spring, but if kept inside the house it could be sooner.

This past week, the butterfly emerged as she and her 5 year old sister watched:

She fed it sugar water, took it to school where she demonstrated it in

both of their classrooms, and allowed it to fly free inside the house.

She wanted to turn it loose outdoors, as some can survive the winter if they can find shelter. Since they went “south” (only about 80 miles) to Starved Rock this

past weekend, she brought it there and released it. It flew a short distance and then did not move much because of the cold. When she returned

later, she found it on the ground, lifeless. She was very sanguine about

this, saying she wants to try this again next spring.

On Thanksgiving Day, the girls visited the Shedd Aquarium in Chicago, where they participated in a children’s program:

Also see:

Birders Start Young

Early Birder