Posted by: Ken @ 1:16 pm

Last spring, two little Bald Eagles, whom the students named “Hope” and “Justice,” successfully fledged from our local nest:

Local Middle School science students will again collect and analyze data about the activities of an eagle family, to try to determine whether traffic density on a nearby highway has any effect upon their behavior. Nest watchers share observations with each other on an Eagle Nest Watch Forum, which had over 50,000 views during its first year of operation. An Eagle Milestone spreadsheet report summarizes selected observations made by adult volunteers during the present and past breeding seasons of the Bald Eagles nest. These are the first eagles to nest in urban Broward County, Florida, since DDT was abolished in the 1970s. The report may be viewed here (PDF). To see all Rosyfinch Ramblings blog posts about these eagles, visit this link.

Based upon the eagles’ change in behavior, I concluded that the first egg hatched (or began to hatch) around noon on Friday, January 22. These changes, first documented by a veteran observer, were:

1) Incubating adult began resting higher in the nest

2) Increased movement and changes of orientation in the incubating adult

3) Frequent looking down into the nest.

Earlier that day, we had found the incubating adult continuously sitting very low in the nest, as it usually appeared since incubation began on December 18, 2009. This was the 35th day of incubation, which is also the average length of time it takes a Bald Eagle egg to hatch.

The next day, January 23, observers reported more movement, almost restlessness on the part of the incubating/brooding adult, which sat higher (more of its body visible above the nest rim) and kept looking into the nest. Later that day, another experienced observer saw both adults together, looking down into the nest, something we saw last year just after the chick hatched. There is probably a second, and possibly a third egg in the nest, yet to hatch.

Since eagles begin incubating as soon as the first egg is laid, and the eggs are deposited about 3 days apart, they hatch out in the order in which they were laid. This gives the first chick a size and strength advantage over the others. If food is scarce, it will out-compete its nest-mates for nourishment, and they will die of starvation, be evicted or even eaten by the oldest eaglet. Last year, both chicks survived and fledged in mid-April. By the end of May they flew off on their own.

Previously, the bird sat so low that we could barely see the top of its head. Often, the incubating female would not be visible at all. This photo was taken in December:

Here is my photo taken on January 23, showing the posture of the incubating female. Note that the full head and part of her back were now visible:

This morning (January 24) there was evidence of a prey item in the nest, something no one has yet reported to happen during the incubation period of the first egg. Unlike Red-tailed Hawks, which I have observed bringing food to the incubating member of the pair, these eagles merely exchange incubating duties and then go off to hunt individually. No one saw the food being brought in, but we saw the adults tearing at it, eating and possibly reaching down to feed the chick.

When we arrived around 9:00 AM this morning, two other regular observers were already there. The female was preening in the melaleuca roost tree to the west of the nest:

The male was sitting on the nest, often looking down and at least once appeared to be tearing at a prey item and possibly feeding an unseen eaglet:

The female took flight, flew east behind the nest, then passed in front of the nest, flying west, and landed in the cow pasture to the NW of the nest tree:

Carrying what looked like small sticks and grasses, the female flew back to the nest and joined the male:

Together, they appeared to rearrange nesting material and also tear at a prey item. Then the male flew up to the first roost tree east of the nest and cleaned his bill. Note the brown tip on the right outermost tail feather that distinguishes this male from the female:

The male continued to roost for a short time, then flew to the south and disappeared:

Posted by: Ken @ 6:25 pm

Since moving to South Florida in 2004, we have taken a rather perverse pride in never needing to turn on our central heating system. Some cool winter nights we might bundle up and throw one of our down comforters on the bed, but it never got so cold long enough to justify turning up the thermostat. We actually did not know whether our heating system even worked!

For nearly two weeks in early January, all of the southern US experienced a prolonged spell of historically low temperatures, For three nights in a row our overnight temperatures dipped very close to freezing. Exotic tropical lizards such as Iguanas fell into stupor and rained down from the trees. We were treated to news stories such as this: Florida cold spell knocks iguanas from trees, and a viral You Tube Video: Frozen Iguanas Fall From Trees.

The cold also took a heavy toll on tropical fish. Commercial fish hatcheries that catered to the pet trade suffered huge losses. Introduced species, particularly tilapia and other cichlids floated to the top of canals and lakes. The ditch along the trail in our local birding patch was littered with the corpses of such species. I realized that this was likely the reason why there were so many herons, storks and ibises along the ditch last week, when I walked the “patch,” and saw an abundance of waders. I also encountered a Cottonmouth Moccasin and two Bobcats. This week I went out again, especially looking for Bobcat tracks.

This Pond Cypress was decorated with nicely spaced white waders:

Wood Storks had exclusive use of my favorite old snag:

Walking along the ditch, I flushed out several more storks:

A small flock of White Ibises flew overhead:

Small birds were scarce. I got a fleeting glimpse of a Swamp Sparrow in its usual thicket, but this Gray Catbird posed for me, showing off its rusty undertail coverts:

A Common Yellowthroat perched on cattails next to the ditch:

An abundance of butterflies made up for the lack of birds. This White Peacock was a small specimen, with only about a 1 1/4 inch wingspan:

This Zebra Heliconian was likewise very small. I wonder why:

An appropriately diminutive Firey Skipper probes a flower with a tongue that is as long as its body:

It had rained quite hard, but briefly, the day before. I knew that it would be a perfect morning for tracking, as the rain would have obliterated the old footprints and bicycle tracks. Sure enough, there were several places in the trails where puddles had formed and partially dried up. This provided a nice clean background. The tracks were mostly from raccoons and deer, but I did find the Bobcat tracks.

Having read up on signs of Bobcats, I learned that, unlike tabby cats, Bobcats do not bury their feces, except those near a den with cubs. Instead, they deposit them conspicuously on rocks or on piles of stones they assemble. This serves to advertise their territory. I found several old piles of scat. Earlier, believing that they might be from Coyotes, I had photographed some of these when still fresh. I’ll spare you a photo, but if you are curious, look here.

There have been no reports of local Coyote sightings, and the placement of piles of feces, mostly on flat rocks in the middle of the trail in Bobcat territory makes me believe they came from the latter species.

Here is an older scat pile that I photographed this week:

Ironically, while I was engaged in scatological studies on the ground, I frightened an Anhinga that had been fishing in the ditch next to the trail. It uttered an irritated squawk, flew low and away, but doubled back, heading right towards me. Expecting a perfect flight shot, I raised my camera and got the bird in the camera’s viewfinder. Just as I was depressing the shutter, the Anhinga let loose with a barrage that was headed right at me! I jumped to my right, and the excrement barely missed my left shoulder. I cannot help but think it was an act of retaliation.

Turning to another unpleasant subject, I again saw several Cottonmouth Moccasins. One, swimming in the ditch, particularly intrigued me. As I watched, the snake encountered a dead fish. It appeared to “smell” it by resting its chin on it and thrusting out its tongue.

Then, to my amazement, the moccasin took the fish into its jaws, shook it as if to break off a piece, then disappeared briefly under the water with it (click on photo for sequential series of pictures):

When it surfaced, the snake’s mouth was empty. In fact, it opened up its mouth for a moment. There did not seem to have been enough time for it to swallow a portion:

Then, the snake moved away, now apparently ignoring the dead fish:

Truly, I thought I had witnessed something new to science! Cottonmouths, with their long fangs and poison glands are so well adapted for killing and eating live prey. Why would one display such an interest in the partially decomposed carcass of a fish? As I subsequently learned, the Cottonmouth’s scavenging habits are well known to science. Indeed, some populations of this species subsist almost entirely upon fish that are dropped by colonial nesting birds such as herons.

References:

South American Journal of Herpetology

The success of this species [Cottonmouth Water Moccasin] on islands is attributable, in part, to a broad trophic niche that encompasses many prey items including carrion. Numerous cottonmouths living on the island of Seahorse Key consume primarily dead fish that are dropped from colonial nesting bird rookeries, but they also prey on rats (Rattus rattus) that are invasive fauna on the island. While alternative prey items (e.g. lizards) are available to newborn snakes, smaller individuals also scavenge for fish carrion at early ages.

Pitviper Scavenging at the Intertidal Zone: An Evolutionary Scenario for Invasion of the Sea.

It is difficult for terrestrial vertebrates to invade the sea, and little is known about the transitional evolutionary processes that produce secondarily marine animals. The utilization of marine resources in the intertidal zone is likely to be an important first step for invasion. An example of this step is marine scavenging by the Florida cottonmouth snakes (Agkistrodon piscivorus conanti) that inhabit Gulf Coast islands. These snakes principally consume dead fish that are dropped from colonial nesting bird rookeries, but they also scavenge beaches for intertidal carrion, consuming dead fish and marine plants, and occasionally enter seawater.

Scavenging by Snakes: An Examination of the Literature

Although it is widely known that most species of snakes readily accept carrion in captivity, the notion of scavenging by wild snakes historically has been rejected or ignored. Herein, we review the literature describing instances of scavenging by snakes and consider the implications of carrion use on their ecology. Thirty-nine published accounts yielded 50 observations of scavenging by snakes (43 from field observations and seven from laboratory studies). Thirty-five species from five families were represented, but pitvipers and piscivorous snakes were represented more frequently than other groups.

Posted on Mon, Feb. 08, 2010

Cold took heavy toll on Florida wildlife

BY CURTIS MORGAN

cmorgan@MiamiHerald.com

Despite four decades of slogging through Everglades marshes and mangroves, wildlife ecologist Frank Mazzotti had never experienced anything like the aftermath of frigid January. The confirmed casualty count so far:

· At least 70 dead crocodiles.

· More than 60 manatee carcasses.

· A bright-side observance of multiple frozen-stiff Burmese pythons, the scourge of the Everglades.

And also, perhaps the biggest fish kill in modern Florida history.

“What we witnessed was a major ecological disturbance event equal to a fire or a hurricane,'’ said Mazzotti, a University of Florida associate professor. “A lot of things have happened that nobody has seen before in Florida.'’

The cold was simply brutal on many tropical plants and animals. Toxic iguana-sicles dropping into the mouths of unfortunate pooches was only the tip of the iceberg that descended for two weeks on South Florida.

While scientists are still surveying losses, it’s already clear that the record chill wiped out shallow corals in the Keys and devastated manatees. A preliminary assessment that Everglades National Park scientists completed last week also documented a broad and heavy toll on everything from crocodiles to cocoplums to butterflies.

Dave Hallac, the park’s chief of biological resources, summed up the impact in a word: “substantial.'’

Cold spells, like hurricanes and fires, are part of the natural cycle in South Florida, and scientists believe the system will recover — but some species will certainly rebound more slowly than others.

“I wouldn’t expect any catastrophic long-term kind of effects,'’ said Luiz Barbieri, chief of marine fisheries research for the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. “Most likely, this has happened occasionally over thousands of years. The system has adapted to these episodic mortality events.'’

Still, mortality numbers like this haven’t been seen in decades in the park.

A record number of endangered manatees died from cold stress, most of them — more than 60 — found in park waters stretching into the Ten Thousand Islands on the Southwest Coast. More than 70 carcasses of North American crocodile were counted, a significant hit to a species removed from the endangered list only three years ago.

About 40 species of pineland plants suffered varying degrees of frost damage. On some tree island, cocoplums looked like they were burned. Half of the population of a caterpillar that morphs into the exceedingly rare Florida leafwing butterfly died.

Then there were the literally countless dead fish — from tiny pilchards to large snook and tarpon.

The report — compiled by Hallac and colleagues Jeff Kline, Jimi Sadle, Sonny Bass, Tracy Ziegler and Skip Snow and based on aerial and water surveys and reports from a host of other observers — underplayed actual losses. It’s impossible to cover an area as vast as the park, and carcasses can sink, float into thick mangroves and easily go overlooked.

TAKING ACTION

While the park has experienced colder days, January’s chill was long and intense, punctuated with overcast skies, rain and one sub-freezing plunge. Mazzotti called it a “perfect storm'’ that left literally no warm refuges.

The chill was particularly dramatic in coastal waters. The park recorded temperatures that hovered below 68 degrees, a cold-stress limit for manatees, for 18 days; and below 60, the stress limit for snook, for 14 days.

“I’m really worried about the snook down here,'’ said Hallac. “It was amazing to see how many of the large, more mature, spawning-age fish were killed.'’

The FWC has already closed snook season until Sept. 1. After reviewing catch reports and samples taken by scientists in coming months, the agency will decide whether to extend the ban on keeping the popular fish or changing regulations to protect any others, Barbieri said.

Cold-blooded reptiles and tropical plants and fish fared the worst, but some Glades species weathered the nasty weather well. Birds, for instance, emerged largely unruffled, and some were observed scavenging fish.

Only one death of an alligator, which reside happily in Louisiana, was reported. Crocs, at the northern end of their range in South Florida, died by the dozens, including one familiar to many anglers who fish Flamingo. The 13-foot, 450-pound croc, tagged as a hatchling in 1986, frequently lurked near the Whitewater Bay boat ramp.

The cold did benefit the park’s battle to control exotic invaders. Frost slammed Old World Climbing Fern, an aggressive vine that smothers natives. Other exotics, from Asian swamp eels to the infamous Burmese python, also took hits scientists intend to further study.

THE STRUGGLE AHEAD

Scientists said recovery rates will vary among species. While snook, popular with sports anglers, has gotten the most attention from the public, the cold may have been more crippling to Goliath grouper, Barbieri said.

The fish, which can grow to massive size, nearly disappeared from Florida but had rebounded so well in recent years that wildlife managers had begun considering lifting a ban on keeping them. Goliaths died in massive numbers in the shallow Glades, considered a prime nursery. They also grow far more slowly than snook, taking six years or more to reach maturity, Barbieri said.

For some hard-hit areas and species, other outside factors can hinder recovery. Everglades marshes and coral reefs aren’t nearly as healthy as they were hundreds of years ago.

Invasive plants, such as Brazilian pepper, weren’t around to crowd out battered natives.

“If you’re totally healthy and get a cold or flu, it’s not a problem. If you’ve got diabetes and heart problems, it could be a lot more serious,'’ Hallac said. “The park is in that kind of compromised condition.'’

Posted by: Ken @ 3:14 pm

Yesterday morning I had a goal in mind as I set out into the mile square area of wetlands, my local birding patch. I would visit the overnight roosting place of the Short-tailed Hawk that I had photographed earlier this week:

Twice before on my morning walks, as passing by a certain maple tree, I was surprised to see a dark-backed hawk emerge from deep within its leaves. The first time, it flew off so quickly that it was impossible for me to see any details of its plumage or shape, except that it was fairly large and looked almost black. Though it appeared to be a raptor with long rounded wings, and left me a bit puzzled as to its identity, I did not think about it much after that.

Then, last week, I was startled when I flushed a similar raptor out of the same tree. As before, it was a dark bird, quite large, and it was dark above and uniformly light underneath. This time I got a better view, and saw that its head was black, in a pattern almost like the “helmet” of some Peregrine Falcons. However, there was no barring on its breast and its wings were not pointed like a falcon’s. About a half hour later I saw my first light morph Short-tailed Hawk making lazy circles above the wetlands.

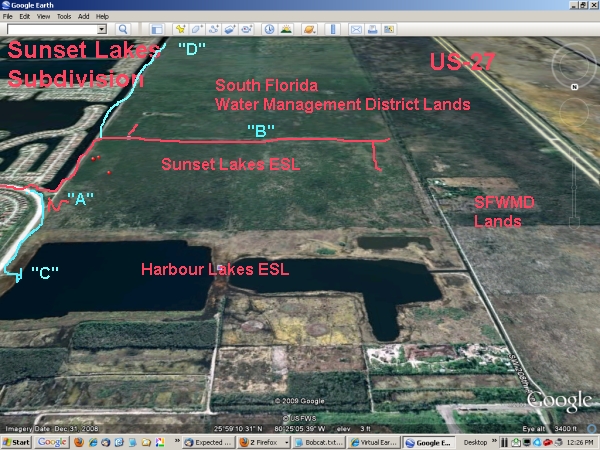

My walk followed the red line on this map, which provides an aerial view looking to the south over the wetland I call the “West Miramar ESL. ” The unpaved E-W road/track in the foreground is Pembroke Road, which will eventually connect with US-27 — how it will traverse the NW portion of the completed C-9 is a mystery to me. [ESL= Environmentally Sensitve Land or Area (ESA) set aside under agreements with developers to “mitigate” the effects of their activities on wetlands. I do not know all the details of the agreements, but rights are conveyed to the South Florida Water Management District (SFWMD) which incorporates them into Water Preservation Areas (WPAs) that are part of the overall Comprehensive Everglades Restoration Plan (CERP) administered by the US Army Corps of Engineers]:

Only after I got home did I connect the two sightings. It is a bit unusual to find a large raptor hiding in the foliage. Accipiters (”bird hawks”) such as the Sharp-shinned Hawks, and sometimes Cooper’s Hawks will hunt that way, hiding in seclusion and darting out to capture a smaller bird. Most Buteos (the group name for many larger hawks such as the Red-tail) seem to prefer perching on an exposed branch that provides a good view of the surrounding area, the better to find rabbits and rodents. However, the Short-tailed Hawk is rarely seen roosting out in the open. It characteristically deep within the branches of a tree, waiting for the ground to warm up and produce thermal currents to loft it effortlessly and allow it to float up very high as it looks for its prey, which consists almost exclusively of other birds. The roost of the Short-tailed Hawk is notoriously hard to find.

I hoped to verify that the hawk had selected that particular Red Maple tree, the largest and fullest of the few hardwoods that grow along the path leading into the heart of the wetland. It was early, and I birded my way along the mile of footpaths that led to that tree. My first stop was a thicket of mostly exotic shrubs, mercifully spared by the landscaping contractors who occasionally groomed the subdivision lands that abutted the wetlands (marked “A” on the above map). To my surprise, I found a half dozen White-winged Doves that appeared to have spent the night there.

One dove settled nicely atop the berm that runs along the dirt road:

Near the dove, a (Western) Palm Warbler posed for an eye-level portrait as it ate a small insect:

A Blue-gray Gnatcatcher approached me so closely that I had to switch my lens to a macro setting, and still could not fit the entire little bird in my viewfinder:

A male Common Yellowthroat peeked out at me from behind his mask:

Continuing along the trail that borders the west side of the 196th Avenue Canal, I reached the intersection of the path that leads westward, into the heart of the wetlands.During summer it is flooded, but the water receded about a month ago and it was now mostly dry. With my binoculars, I checked out the trail, as it sometimes is occupied by deer and once, a Bobcat. This time, I could make out the figures of one or two Black Vultures on the ground, about a half mile away. Then I thought I saw a four-legged creature just behind the vultures. Keeping to the side of the trail to break up my silhouette, I moved closer very carefully.

A ditch runs along the north side of the trail, and it was teeming with fish. During the wet summer, the fish were free to swim everywhere in the wetland, but now they were concentrated in the ditch. This was an ideal situation for long-legged waders, especially tactile feeders such as Wood Storks and ibises.

As I moved along parallel to the ditch, the startled birds, such as this Wood Stork, flew up and moved ahead of me:

A Tricolored Heron circled back behind me:

A group of immature storks clustered on a treetop:

In the distance, I picked out the subtle differences between an immature Little Blue Heron, on the left, and a Great Egret:

Despite all the distractions, I kept working my way, trying to stay up on the edge of the trail out of sight of whatever creature might be ahead. When I was about 1/4 mile from the vultures (which were about at the point marked with a “B” on the topo map), I took several photos. None turned out very well.

Although heavily cropped, my images revealed not one, but two Bobcats:

The cats were apparently eating a prey item, and the vultures were standing by, hoping for some scraps. I kept moving nearer, as quietly as possible, but when I looked again they had disappeared. Then, I walked down past the area where they had gathered, and was surprised when both suddenly ran across the trail only about 50 feet ahead of me. There was no time to grab the camera.

I walked back, hoping to find some nice tracks in puddles, but among the many raccoon tracks, found only one that appeared to have been an overlay imprint of the back foot over the front (as an expert tracker pointed out to me, this is technically an “overstep or indirect register as it’s termed where the hind foot does not always go exactly into the front print:”

While looking for the tracks, I kept to the north side of the trail, hoping that the sun, now to my right, would cast shadows to make them show up better. Of course, I kept an eye out for snakes, but my peripheral vision picked up flash of white, only about three feet to my left:

The snake was about four feet off the trail. I only had my long lens, and (in my heightened state of awareness) I did not want to back up into the high grass on the other side of the path to try and fit its whole body into the picture. When I blocked the sun it reacted again. I realized that my shadow had passed over the snake as it was resting in the sun, and this caused it to go into its classic threat display. Now I know first hand why they are called “Cottonmouths!”

Posted by: Ken @ 1:20 pm

Yesterday provided brief respite from a long and record-breaking cold spell in South Florida, with predictions that it will extend well into next week. Our family and friends up north and in the mountains of New Mexico and Arizona may chuckle when we complain about overnight lows in the high 30s and daytime highs that struggle to get out of the 50s. For the first time, after living here for over five years, we finally had to turn on the central heat. The wind chill is expected to dip to the mid 20s tonight.

I took advantage of the warmth to get out into our local birding patch. The water conservation impoundment that I call the “West Miramar Environmentally Sensitive Area or Land (ESA or ESL)” is more accurately described as the southeastern corner of the Broward County Water Preserve Area, established under the Comprehensive Everglades Restoration Program (CERP), as identified in the federal Water Resources Development Act (WRDA) of 2000. The rainwater impoundment areas aid in reducing seepage, recharge the groundwater to improve water supply to urban areas, and prevent saltwater intrusion. They also are part of the system of impoundments and canals that remove phosphates from agricultural runoff and restore sheet flow to the Everglades.

As usual, I had no particular target birds in mind, but I was treated to a new species for my “photographed” list. A hawk was circling lazily overhead. Glancing quickly, I saw a reddish tint to its tail and almost jumped to the conclusion that it was the common Red-tailed Hawk. However, a typical Red-tail usually has a band of streaks on its lower breast, and a distinctive black “patagial” mark that extends about 1/3 of the way out from its body under the leading edge of each wing. In contrast, this bird had a clear white breast and the leading edges of its underwings were also very white. It was a Short-tailed Hawk, one of the rarest hawks in the United States. A tropical species, it breeds regularly only in Florida, and tends to spend the winter in the southern part of the state.

ADDENDUM: As it turns out, my observation was not that unusual, although I could not find reference to the reddish tail in my field guides, I just discovered this reference: http://www.fosbirds.org/FFN/PDFs/FFNv01n2p14-17Ogden.pdf

Florida Field Naturalist, Vol. 1, - Fall, 1973: Strong sunlight shining through the spread tail of a soaring white-phase Short-tail (and in some dark ones) creates the illusion of a reddish-brown tail, rather than pale grey.

The Short-tailed Hawk occurs in two color morphs, one very dark, and, less commonly, a light form as was this bird; despite its name, the tail is about average size for the Buteo group:

As I stood quietly in a small damp hollow, surrounded by shrubs, a Prairie Warbler emerged from the brush and looked at me quizzically:

A tiny Blue-gray Gnatcatcher gleaned spiders from the clumps of Brazilian Pepper berries:

There are only a couple of ancient cypress or oak snags left standing since Hurricane Wilma. This one hosts a Wood Stork and a Great Egret that looks for all the world as if it has a broken neck that it is holding up with one foot (actually, it is scratching):

As the day warmed up, dragonflies became active, including this rather unusual Great Pondhawk (click on photo to select the original large closeup view of its face):

An exotic dragonfly from Japan, the Scarlet Skimmer, was presumably brought into Florida on ornamental plants. It is now fairly common:

Before it turned cold, as the end of 2009 approached, a walk in Chapel Trail Nature Center, just to the north, yielded a close view of a Loggerhead Shrike:

This female Northern Cardinal was very shy, permitting me only a glimpse of her face:

Two Purple Swamphens that survived the extermination campaign

Still morning air allowed nice reflections during our visit to Stormwater Treatment Area (STA) 2/3. Tricolored Heron:

Roseate Spoonbill:

A pair of White Pelicans takes flight:

Also located within the Broward County Water Preserve Area, the West Pines Soccer Park and Wildlife Preserve provided a nice view of this Red-bellied Woodpecker:

The year 2009 finished off with a “Blue Moon.” Here it is, straight out of the camera, as it was just clearing the rooftops across our lake:

By accident, a neighbor celebrated the New Year by sending up some rockets just as I was snapping an overexposed image of the rising Blue Moon:

Finally, I could not resist a little editing to celebrate the Blue Moon on New Years Eve– the next one will not come until 2028: