Posted by: Ken @ 3:14 pm

Yesterday morning I had a goal in mind as I set out into the mile square area of wetlands, my local birding patch. I would visit the overnight roosting place of the Short-tailed Hawk that I had photographed earlier this week:

Twice before on my morning walks, as passing by a certain maple tree, I was surprised to see a dark-backed hawk emerge from deep within its leaves. The first time, it flew off so quickly that it was impossible for me to see any details of its plumage or shape, except that it was fairly large and looked almost black. Though it appeared to be a raptor with long rounded wings, and left me a bit puzzled as to its identity, I did not think about it much after that.

Then, last week, I was startled when I flushed a similar raptor out of the same tree. As before, it was a dark bird, quite large, and it was dark above and uniformly light underneath. This time I got a better view, and saw that its head was black, in a pattern almost like the “helmet” of some Peregrine Falcons. However, there was no barring on its breast and its wings were not pointed like a falcon’s. About a half hour later I saw my first light morph Short-tailed Hawk making lazy circles above the wetlands.

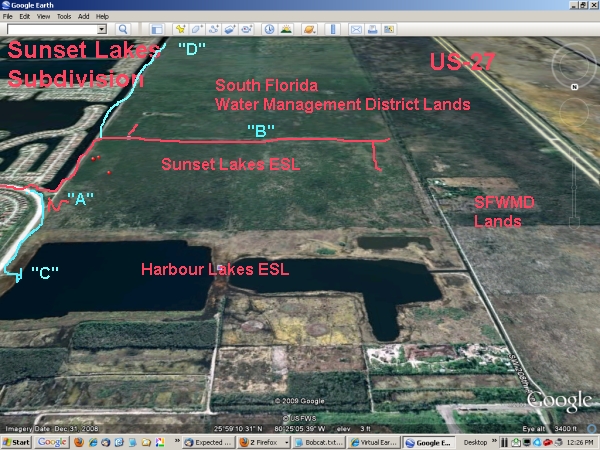

My walk followed the red line on this map, which provides an aerial view looking to the south over the wetland I call the “West Miramar ESL. ” The unpaved E-W road/track in the foreground is Pembroke Road, which will eventually connect with US-27 — how it will traverse the NW portion of the completed C-9 is a mystery to me. [ESL= Environmentally Sensitve Land or Area (ESA) set aside under agreements with developers to “mitigate” the effects of their activities on wetlands. I do not know all the details of the agreements, but rights are conveyed to the South Florida Water Management District (SFWMD) which incorporates them into Water Preservation Areas (WPAs) that are part of the overall Comprehensive Everglades Restoration Plan (CERP) administered by the US Army Corps of Engineers]:

Only after I got home did I connect the two sightings. It is a bit unusual to find a large raptor hiding in the foliage. Accipiters (”bird hawks”) such as the Sharp-shinned Hawks, and sometimes Cooper’s Hawks will hunt that way, hiding in seclusion and darting out to capture a smaller bird. Most Buteos (the group name for many larger hawks such as the Red-tail) seem to prefer perching on an exposed branch that provides a good view of the surrounding area, the better to find rabbits and rodents. However, the Short-tailed Hawk is rarely seen roosting out in the open. It characteristically deep within the branches of a tree, waiting for the ground to warm up and produce thermal currents to loft it effortlessly and allow it to float up very high as it looks for its prey, which consists almost exclusively of other birds. The roost of the Short-tailed Hawk is notoriously hard to find.

I hoped to verify that the hawk had selected that particular Red Maple tree, the largest and fullest of the few hardwoods that grow along the path leading into the heart of the wetland. It was early, and I birded my way along the mile of footpaths that led to that tree. My first stop was a thicket of mostly exotic shrubs, mercifully spared by the landscaping contractors who occasionally groomed the subdivision lands that abutted the wetlands (marked “A” on the above map). To my surprise, I found a half dozen White-winged Doves that appeared to have spent the night there.

One dove settled nicely atop the berm that runs along the dirt road:

Near the dove, a (Western) Palm Warbler posed for an eye-level portrait as it ate a small insect:

A Blue-gray Gnatcatcher approached me so closely that I had to switch my lens to a macro setting, and still could not fit the entire little bird in my viewfinder:

A male Common Yellowthroat peeked out at me from behind his mask:

Continuing along the trail that borders the west side of the 196th Avenue Canal, I reached the intersection of the path that leads westward, into the heart of the wetlands.During summer it is flooded, but the water receded about a month ago and it was now mostly dry. With my binoculars, I checked out the trail, as it sometimes is occupied by deer and once, a Bobcat. This time, I could make out the figures of one or two Black Vultures on the ground, about a half mile away. Then I thought I saw a four-legged creature just behind the vultures. Keeping to the side of the trail to break up my silhouette, I moved closer very carefully.

A ditch runs along the north side of the trail, and it was teeming with fish. During the wet summer, the fish were free to swim everywhere in the wetland, but now they were concentrated in the ditch. This was an ideal situation for long-legged waders, especially tactile feeders such as Wood Storks and ibises.

As I moved along parallel to the ditch, the startled birds, such as this Wood Stork, flew up and moved ahead of me:

A Tricolored Heron circled back behind me:

A group of immature storks clustered on a treetop:

In the distance, I picked out the subtle differences between an immature Little Blue Heron, on the left, and a Great Egret:

Despite all the distractions, I kept working my way, trying to stay up on the edge of the trail out of sight of whatever creature might be ahead. When I was about 1/4 mile from the vultures (which were about at the point marked with a “B” on the topo map), I took several photos. None turned out very well.

Although heavily cropped, my images revealed not one, but two Bobcats:

The cats were apparently eating a prey item, and the vultures were standing by, hoping for some scraps. I kept moving nearer, as quietly as possible, but when I looked again they had disappeared. Then, I walked down past the area where they had gathered, and was surprised when both suddenly ran across the trail only about 50 feet ahead of me. There was no time to grab the camera.

I walked back, hoping to find some nice tracks in puddles, but among the many raccoon tracks, found only one that appeared to have been an overlay imprint of the back foot over the front (as an expert tracker pointed out to me, this is technically an “overstep or indirect register as it’s termed where the hind foot does not always go exactly into the front print:”

While looking for the tracks, I kept to the north side of the trail, hoping that the sun, now to my right, would cast shadows to make them show up better. Of course, I kept an eye out for snakes, but my peripheral vision picked up flash of white, only about three feet to my left:

The snake was about four feet off the trail. I only had my long lens, and (in my heightened state of awareness) I did not want to back up into the high grass on the other side of the path to try and fit its whole body into the picture. When I blocked the sun it reacted again. I realized that my shadow had passed over the snake as it was resting in the sun, and this caused it to go into its classic threat display. Now I know first hand why they are called “Cottonmouths!”