Posted by: Ken @ 10:28 pm

Today, fast approaching the three-quarter century mark, I am penning my 300th post in Rosyfinch Ramblings. Before the days of File Transfer Protocol, and before the word “blog” was invented, I created the rosyfinch.com web suite devoted to the birds of the Sandia Mountains, near our former home in New Mexico. In those days I wrote daily updates in HTML code by hand, and uploaded strings of ASCII characters via a telephone modem. When I started using blogging software in 2006, I simply intended to record memories from my childhood in New Jersey. In my fifth post, Discovering Birds, I tried to remember how and why I ever got into bird watching.

How lucky I was to have had a father with an infectious interest in the natural world. I remembered those long walks with him in the woods (Habitats and Inhabitants) and, more recently on Father’s Day, described how I especially felt his his loss. Now we and our children try to inspire our grandchildren to put away the Wii’s, Game Boys and iPods and get outdoors. See Birders Start Young, and Early Birder.

I recounted adventures from my medical career, as the Rookie Doctor in Town , and wondered Why It’s Called Medical “Practice”. Then, suddenly and unexpectedly, I entered the field of public health, only two weeks after receiving a telegram: Greetings, You’ve Been Drafted . Providing medical care in the aftermath of Hurricane Camille, and Closing the Grand Canyon were but a couple of highlights of many exciting experiences in public health practice.

I always wanted to marry a bird-watcher, but this never happened until after I retired to the mountains of New Mexico. Don’t look so startled– Mary Lou and I just celebrated our 50th Wedding Anniversary, but she suffered as an SOB (spouse of a birder) for many years before I could say “Finally, I’m Married to a Bird-Watcher.“

We do not feel the need to travel far and wide to enjoy the beauty of nature, whether from the windows of home, in backyards, or in local patches of semi-wild land. From early childhood, I have found Beauty in the Commonplace, mostly in the good old USA. While Mary Lou and I keep life bird lists, and have taken several wildlife-oriented jaunts and cruises, neither of us has a compulsion to see all the birds of the world. We greatly enjoy seeing just that tiny sample of the avian multitude that live in, or visit our neighborhood.

Muscovy Duck in flight:

No, this is not a Frog-mouthed Four-legged Crow, but rather part of a ritualistic encounter between two male Boat-tailed Grackles in our yard. They take turns posturing, and soon one will open his mouth and flap his wings while the other points his bill to the sky. They posture and then the other bird does the same. At no time did both birds sing and flap at the same time. This went on for several minutes, until they peacefully walked away from each other and resumed catching dragonflies on the lawn. Click on image and view sequential photos of the “dance” at the “comment” link below the photo.

Boat-tailed Grackles perform a ritual “dance:”

I’m still experimenting with my little Canon A-1100 IS point-and-shoot. It packs 12.1 megapixels. This is a cropped image zoomed 4x optically to about 25 mm focal length. If you click on the photo, an image will appear below it, lightly cropped and not zoomed at all, about 6mm focal length:

Great Egret:

The Canon A-1100 takes surprisingly sharp macro photos, such as of this Garden Snail (Zachrysia provisoria):

This big Lubber grasshopper was on the glass of our patio door, again captured by my little point-and-shoot:

I had been hearing little chirps in my garage in the vicinity of the corner where I store my fertilizer and garden stuff. The chirps would stop whenever I got near, and I could not find their origin, though I presumed it might be a tree toad or frog, or maybe a Mediterranean Gecko. When potting a plant one morning I reopened a bag of potting soil. Inside were at least 6 or 7 of these little frogs, about 3/4 inch in length. Greenhouse Frogs live in plant litter and their tadpoles develop into frogs inside the eggs, so they don’t need a pool or pond to breed. They lack webbing between their toes and have been erroneously called toads. Native to the Caribbean, they have invaded most of the Florida peninsula. Listen to an mp3 of their little chirps that I heard: puca.home.mindspring.com/mp3s/Greenhouse.Frog.mp3

A Green Heron dropped by our back patio just before we departed for Illinois:

When the birding slows down there are always butterflies, and it is fun to separate the Queen…

This is the fourth of four posts on this subject. First Installment is here

This is the fourth of four posts on this subject. First Installment is here

During the late 1960’s in New Orleans, one of my volunteer projects was to institute a weekly evening medical clinic in the Lower Ninth Ward. This was accomplished with much help from local citizens (notably Mrs. Allie Mae Williams and Mrs. Morrice Johnson) and medical students from Tulane University. Sadly, this old neighborhood was devastated by Hurricane Katrina.

A very memorable experience was on Friday, April 5, 1968, the day after Dr. Martin Luther King was assassinated. I had to park quite a distance from the shotgun frame house that served as our Lower Ninth Ward free clinic. Parked cars had already taken up both sides of the shell road for more than a block. People were out on their front porches. Usually, we exchanged cheerful waves to the sounds of jazz music as I trudged along with my white coat and little black bag. That evening there was silence. There seemed to be agony oozing out of the houses, and I found it hard just to look up.

When I entered the waiting room I saw that the power had failed, a not uncommon occurrence. In the gathering darkness, I could barely see all the people who were silently awaiting my arrival. A couple of Tulane medical students had gotten there before me, and they were already busy triaging the patients and getting them ready for the physician. We examined by candlelight and flashlight. Gloom pervaded the day and then, the night.

The next week pain had turned to tension, and as I walked to the clinic I encountered a gang who had surrounded two fighting men. One had a knife, and the other wielded a baseball bat. As they scurried about, the crowd ran along with them and pressed around them. Did I ever feel silly, standing there in my white coat like the ringside doctor waiting for my victim! Luckily, both were simultaneously restrained without signs of major injuries.

This is the third of four posts on this subject. First Installment is here

This is the third of four posts on this subject. First Installment is here

Since my assignment to the hurricane shelters after Hurricane Camille in 1969 was part of the Tulane University School of Public Health academic program, I was required to evaluate the experience. To accomplish this, I devised a system to track all medical visits by shelter occupants during the first two months following the storm. Then these data were compiled and analyzed.

On April 3, 1970 I presented a paper on the epidemiology of Hurricane Camille at the Fifth Joint Meeting of the Clinical Society and Commissioned Officers Association in Washington, DC. A summary may be viewed at this link.

The paper follows two major subgroups of shelter residents, one white and the other black. The two groups provided opportunity for comparisons because they occupied separate shelters in Belle Chasse at the same time, both moved down to Buras on the same day, and both formed relatively stable populations into the 3rd and 4th weeks after the storm.

There was a progressive increase in the utilization of medical services in both shelter populations during the first two weeks after the storm. There were differences in their patterns of incidence of respiratory infections, open injuries, and “functional” conditions. Factors other than race alone may have accounted for these differences. Geographic mobility and access to damaged homes appeared to correlate positively with the incidence of open injuries.

My paper mentions some of the issues we encountered in the shelters. Of interest is the fact that the people of Plaquemines Parish were quite accustomed to evacuating in advance of hurricanes. When Camille threatened, people took the evacuation very seriously. Most expected that they would be back in their homes within a day or so. Therefore, many did not take their medication supplies. Birth control pills were left behind, causing a large number of women to begin withdrawal menstrual bleeding at once. Pads were quickly in short supply! Early on, an average of over 30 persons were crowded into each classroom. The white shelters had especially large numbers of pet dogs, tied up outside their owners’ windows.

I was one of the few, perhaps the only, US Public Health Service Commissioned Officer to have been extensively involved in immediate medical relief efforts following Hurricane Camille. Much has changed since then. According to a January 18, 2006 DHHS press release, more than 2,000 USPHS Commissioned Corps officers were deployed to the Gulf region before, during, and after hurricanes Katrina and Rita. “They set up and staffed field hospitals and emergency medical clinics, treated sick and injured evacuees, ensured hospital structures, food supplies, and water supplies were safe, conducted disease surveillance, and worked closely with local and state health authorities to address other immediate and long-term public health needs.”

As bad as Camille was, we were all thankful that it was not the “big one” that everyone talked about, the hurricane that would slosh water up into Lake Pontchartrain and force it over the levees into the East Bank of New Orleans. Of course, Hurricane Katrina was to do something very similar. The storm is estimated to have been responsible for $125 billion in damage, the costliest natural disaster in U.S. history.

Remarkably, these words were written in 1999: “For many, Camille is a distant memory, an historical footnote from a time long gone. But Camille is also a harbinger of disasters to come. Another storm of Camille’s intensity will strike the United States, the only question is when. When this future storm strikes, it will make landfall over conditions drastically different from those in 1969. The hurricane-prone regions of the United States have developed dramatically as people have moved to the coast and the nation’s wealth has grown. Estimates of potential losses from a single hurricane approach $100 billion.”

Next entry on this topic (fourth of 4) HERE

(This is the second of four posts on this subject. First Installment is here

(This is the second of four posts on this subject. First Installment is here

Working in the hurricane shelters after Camille, I found the clinical experience to be not very dramatic. Hurricane shelter medical practice was like busy general practice. Minor conditions, such as fire ant bites and skin infections, prevailed. As the days passed, there were fairly rapid changes in the assortment of conditions treated. Were these changes part of predictable trends? We expected epidemics, but with the work divided between many volunteer physicians and nurses, we weren’t sure that we could even detect an epidemic early enough to take action.

Donations of medical supplies were often inappropriate. Physicians’ samples, though welcomed, presented problems of sorting, storage and outdated drugs. Donated hearing aid batteries far exceeded needs. Shoes were ill-fitting, often because donors forgot to tie them together in pairs.

During the first month after the storm, refugees on the West Bank of Plaquemines Parish accumulated nearly 30,000 person-days of exposure to the peculiar risks of life in the hurricane shelters. Professional volunteers rapidly decreased in number as the days passed, and public health personnel took over most of the duties.

There were 6 racially segregated shelters, (5 high schools and, briefly, a US Naval Air Station) which served 4 relatively distinct populations. Three of the shelters were located in the northern part of the Parish, in Belle Chasse (just south of New Orleans). A fourth opened 3 days after the storm, in Port Sulphur. After flood waters had receded and utilities were restored, 2 weeks after the storm, all of the refugees were transported to the 5th and 6th shelters, in Buras, 50 miles south of Belle Chasse.

Plaquemines Parish was in open rebellion against the Federal government over civil rights issues. Because I was attached to the State health department and not in uniform, my federal credentials were not questioned. The Parish rejected all forms of Federal assistance. Descendants of the notorious segregationist Judge Leander Perez presided over “the last political kingdom in America.”

“…Plaquemines Parish, Louisiana [is] a racial and ethnic gumbo in the swamps ruled for over 60 years by the all-powerful Perez family. From the time Judge Leander Perez came to power in 1919, he made headlines across Louisiana and throughout the country. The Judge and his two sons clamped down on all political opposition, restricted free elections, disenfranchised black citizens, and made millions of dollars from oil. In the 50s and 60s Judge Perez became a national spokesman for racial segregation, bankrolling George Wallace and going so far as to outfit an old Civil War fort as a high security prison for any civil rights demonstrators who dared to venture into his county.

“When the Judge died in 1969, Perez power was secure. But by 1980 his two sons began to feud with each other over their empire, and long-simmering democratic forces came to a boil. This was the exciting atmosphere that filmmakers Louis Alvarez and Andrew Kolker capture in The Ends of The Earth, as the first free elections in Plaquemines were held and the long-oppressed Blacks of the parish organized to get the basic services which had been denied to them for so long.”

Camille was no respecter of status, and the Sheriff and members of the Parish Council were among those whose homes were destroyed.

Continued– see part 3 of 4 here

(This is the first of four installments on this subject).

(This is the first of four installments on this subject).

With the mild 2006 hurricane season barely fading from memory, we now have a professor from Colorado telling us that next year’s hurricane season will be worse than most. We moved to South Florida in 2004, just in time for two of the worst hurricane swarms in US history.

Here, in 2005, Hurricane Katrina loomed in from the Atlantic and veered southward at the last moment, sparing us major damage. Of course, Katrina went on to devastate New Orleans. Then, as Katrina approached the upper Gulf Coast, we recalled our experience with Hurricane Camille– the horror we felt on Sunday evening, August 17, 1969, a family of six crouching in our home, below sea level on the West Bank of New Orleans, hearing the windows rattle and tree limbs shatter.

A resident in General Preventive Medicine residency under a USPHS/Tulane University program, I was just starting a rural public health rotation with the Louisiana State Health Department. That morning I had finished a 24 hour shift as Officer of the Day at the New Orleans Public Health Service Hospital, and was able to return home Sunday at noon, aware that we were facing the threat of a mighty storm.

A portable radio was our only contact with the outside world. We stayed awake all night listening to reports of the storm’s position and the status of the storm drainage pumps. We felt relief that the storm was quite compact and that the eye had passed some 35 miles to our east, but we were alarmed to hear that major flooding had occurred within a couple of miles of our home, and that thousands had lost their homes and were crowded into nearby hurricane shelters.

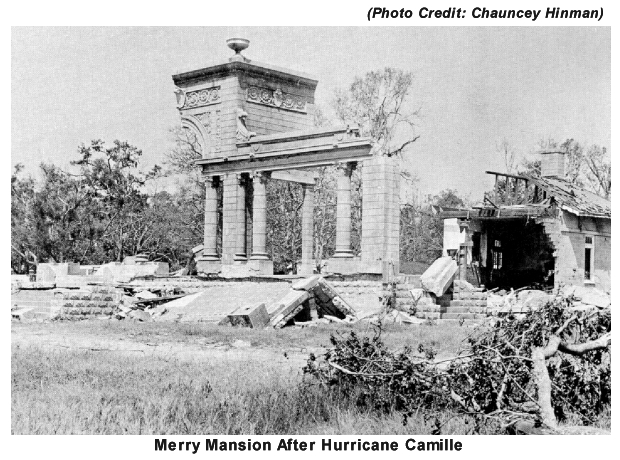

Camille, with an unusually compact eye of 5 miles diameter, was then the most intense hurricane ever to strike the United States mainland. Winds exceeding 200 miles per hour and an extremely low central pressure combined to generate the highest tides ever recorded on the Gulf Coast. A wall of water, up to 30 feet high, surged through the populous Bay St. Louis - Pass Christian Area of Mississippi. Houses that had withstood many previous storms were reduced to piles of rubble by the ravages of wind and water. In many cases, all that remained of homes and businesses were the concrete foundation slabs.

This was the unusual aspect of Hurricane Camille — widespread destruction of homes caused large numbers of refugees to remain homeless for long periods of time. Of the 284 known deaths, only 5 occurred in Louisiana, 3 of these in Plaquemines Parish (County). This is the Parish that occupies both banks of the final 80 miles of the Mississippi River, just below New Orleans. Early evacuation of nearly all the residents of the southernmost low-lying areas undoubtedly averted hundreds of casualties. On the West Bank of the river south of Empire, where 11,000 people lived, destruction was virtually total. Here alone, over 3000 homes were either completely destroyed or sustained major damage. Flood waters, up to 17 feet deep, persisted for nearly a week after the storm. In Buras, two high schools, later to be used as shelters, were flooded up to the second floor level.

This was the unusual aspect of Hurricane Camille — widespread destruction of homes caused large numbers of refugees to remain homeless for long periods of time. Of the 284 known deaths, only 5 occurred in Louisiana, 3 of these in Plaquemines Parish (County). This is the Parish that occupies both banks of the final 80 miles of the Mississippi River, just below New Orleans. Early evacuation of nearly all the residents of the southernmost low-lying areas undoubtedly averted hundreds of casualties. On the West Bank of the river south of Empire, where 11,000 people lived, destruction was virtually total. Here alone, over 3000 homes were either completely destroyed or sustained major damage. Flood waters, up to 17 feet deep, persisted for nearly a week after the storm. In Buras, two high schools, later to be used as shelters, were flooded up to the second floor level.

The next morning, responding to calls for medical volunteers, I contacted my program director to request annual leave, and appeared at Belle Chasse High School shelter to offer assistance. There was an outpouring of volunteers. High school students helped mind and care for the children, and several doctors, nurses and pharmacists responded. I extended my leave period another day, as there was quite a demand for medical services. Luckily, the Louisiana State Heath Officer visited the shelter and saw me working. As supervisor of the public health portion of my residency training, he immediately assigned me to hurricane relief. This substituted for my scheduled rotation to another rural Parish Health Unit upstate.