We knew we were back in Florida when…

…our arriving flight suddenly entered a thunderstorm and, due to wind shear had to abort a landing just short of touchdown. To boot, its second attempt was thwarted on final approach, when the runways switched directions.

…our first chore at home was to open the hurricane shutters and put out BBQ and deck furniture.

…I found this Cuban Treefrog hiding behind the shutters:

…a Tricolored Heron foraged along the newly-submerged edge of our lawn:

…these nine ducklings greeted us (hatched out on May 16th, all survived and stayed together– the two in foreground are adults):

…we saw this a wild sky at sunset (unedited photo):

Squalls from Hurricane Gustav’s feeder bands awakened us this morning. Tropical Storm Fay had already dumped more than a foot of rain during the past week, and our lake level rose three feet, about as high as we have ever seen.

These White Ibises crowded against a neighbor’s fence to avoid getting their feet too wet as they patrolled the lake’s margin:

According to the U of Florida Extension Web Site, the “largest treefrog in North America is the Cuban treefrog (1.5 to 5 inches in body length), however it is not native to North America. This species was introduced to southern Florida from the Caribbean and has continued to spread in Florida. Cuban treefrogs have been documented as far north as Cedar Key on the Gulf Coast, Jacksonville on the Atlantic Coast, and the Orlando area in mid-Florida, and they are expanding their range.”

The Cuban Treefrog’s very large toe pads and warty back, seen on our visitor, also help distinguish it from native treefrogs:

“Many people have reported that after they first noticed a Cuban treefrog in their yard, they noticed the gradual disappearance of the other frogs, toads and even lizards. That’s because Cuban treefrogs are voracious eaters — and unfortunately they eat Florida’s native frogs, toads, and lizards, in addition to insects and spiders. In fact, Cuban treefrogs are SO successful at taking over habitat and eating Florida’s native species that they are considered an invasive exotic (non-native) species — they are a threat to the biodiversity of Florida’s native ecosystems and wildlife.”

In a little over two months, the three Rosy-finch species will return for the winter to Sandia Crest, just east of Albuquerque, New Mexico. Start planning your trip, which might coincide with attending the 2008 Festival of the Cranes at Bosque del Apache NWR scheduled for November 18-23

The full daily schedule of 2008 Festival of the Cranes events (workshops, tours, hikes, exhibits and lectures, dinner, keynote address) may be found at the new Friends of the Bosque Web site. There will even be two tours of the Trinity Site, where the first atomic bomb was detonated.

This week marks the third anniversary of the death of Ryan Beaulieu, the young New Mexico birder and rosy-finch researcher. His family and friends have established a scholarship in his honor, administered by the Central New Mexico Audubon Society.

For more information about the Ryan Beaulieu Memorial Youth Scholarship, visit this link.

Read about Ryan:

High Fives to an “Awesome” Birder

Ryan and the Winter of 2004-2005

Visit Ryan Beaulieu’s Memorial Page

Cole Wolf, another expert young bird researcher, artist, and one of Ryan’s close friends, was awarded the 2008 Ryan Beaulieu Memorial Youth scholarship.

Cole captured this dramatic photo of rosy-finches mobbing a Red-tailed Hawk at Sandia Crest (click on the photo for a full-screen wide view of the action):

The following is Cole’s report on his experience at the Maine Audubon Youth Birding Camp:

I was fortunate enough to be the recipient of the 2008 Ryan Beaulieu Memorial Youth Scholarship; I used the scholarship to attend Maine Audubon’s Youth Birding Camp on Hog Island, ME.

Hog Island is a private sanctuary owned by Maine Audubon located off the state’s southern coast. I spent five nights on the island with eleven other teens interested in birds and nature. On the morning bird walks around the island we heard dozens of Black-throated Green Warblers and Northern Parulas along with the occasional Blackburnian Warbler. White-throated Sparrows were also common. Common Loons, Black Guillemots, and groups of Common Eiders were often seen from shore. Unfortunately our group missed the Ruffed Grouse that wandered into camp one morning. On the final morning our leaders set up mist nets; we banded a Carolina Wren and several Purple Finches. Besides birds we also saw a Porcupine and several Garter Snakes on the island.

Although we stayed on Hog Island, during the day we usually went birding elsewhere. Several times we spent mornings on the mainland looking for warblers and other woodland birds. I saw fifteen species of wood-warblers during the camp, including Canada, Magnolia, Chestnut-sided, and Pine. Besides the many warblers we saw Red-shouldered Hawk, Yellow-bellied Sapsucker, Eastern Wood-Pewee, Blue-headed Vireo, and Baltimore Oriole. We also spent time in marshy habitats and had birds like Black Duck, Alder Flycatcher, Swamp Sparrow, and Bobolink. One of the most memorable experiences of the trip was having lunch overlooking a Bobolink colony. There were at least four pairs in the fields around us and the males sang and displayed almost constantly.

Of course we also visited Maine’s most famous birding locations: Eastern Egg Rock and Acadia National Park. Eastern Egg Rock is one of the sites where Atlantic Puffins have been reintroduced to Maine. Although it was a foggy day, we still managed to see dozens of Puffins and Guillemots. We also saw four species of terns: Common, Arctic, Roseate, and Black. Though Black Terns are common in New Mexico, the species is endangered in Maine and had never before been recorded at Eastern Egg Rock. On the trip back we got close-up looks at all three species of Scoters.

We spent a full day at Acadia National Park. Besides spectacular scenery, highlights included the only Northern Gannet of the trip, a family of Peregrine Falcons, several Least Flycatchers, and a singing Veery.

I would like to thank the Ryan Beaulieu Memorial Fund for paying to send me to Hog Island. I would also like to thank CNMAS’s Education and Scholarships committee for selecting me to receive the scholarship. It was a very memorable experience and I saw lots of great birds. I encourage you to donate to the Ryan Fund; it makes experiences like mine possible.

American Goldfinch:

After three weeks in Illinois, I finally shook off what had been ailing me and we visited Dick Young/Nelson Lake Forest Preserve in Batavia. Since the bull thistle was starting to go to seed, I hoped to capture images of American Goldfinches perched on the flowers and fluffy seed heads, but was disappointed. Only a handful of goldfinches were seen, usually flying over or perched on tree limbs. Nearly all seemed to be males in bright plumage. Were the females now incubating? The birds depend upon thistle for nesting material and food for their young. Being new to Chicagoland, I do not know whether the birds are nesting on schedule, or whether thistle might be maturing a bit late and thus delaying the nesting cycle. In New Mexico, the Lesser Goldfinch often nested quite late– I once saw one feeding fledgelings about a week into September.

House Wren:

Few birds were singing, besides Song Sparrows and a couple of Indigo Buntings. I heard a snippit of a Swamp Sparrow’s song, and the call of a Yellow-billed Cuckoo, and several House Wrens fluttered and quietly chattered in the trailside grasses and weeds. It was next to impossible to photograph them. The above image was the only one I could obtain.

I tried to identify one small bird that was determined to escape from view. I thought it was another wren, but never got the binoculars on it. It seemed to disappear every time I clicked the shutter. When I reviewed my photos later, to my surprise, it was captured on one photo. It appears not to be a wren after all. It has a hint of yellow color, its tail appears longer than that of a wren, and it lacks the characteristic barring of its flight feathers and tail.

More likely, this furtive lurker was a Common Yellowthroat:

An Eastern Tailed Blue butterfly caught my attention:

Yellow composites abounded. I called these “Black Eyed Susan,” but could stand corrected:

These DYCs (D**n Yellow Composites) are somewhat different, having 14 instead of eight petals; are they Brown-eyed Susans?:

These guys also had 14 petals, but did not have dark centers– they may be Cup-plants:

There was a large patch of tall plants with pink flowers that attracted butterflies:

Posted by: Ken @ 9:29 am

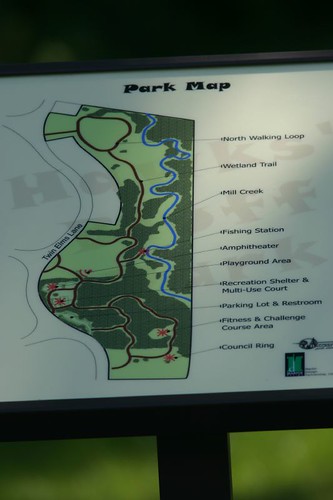

Weather has turned cooler, and I am getting my walking legs back. We visited Hawks Bluff Park in Batavia, Illinois, only a few doors away from our daughter’s family home. The only singing birds were a couple of Indigo Buntings, some Song and Field Sparrows, a Northern Cardinal, and an Eastern Wood Pewee. The Cooper’s Hawk family was much in evidence, helping to keep avian photo opportunities to a minimum during these Dog Days of summer. Our granddaughters are part of the “No Child Left Inside” movement, and the new park is a wonderful addition to their neighborhood.

New interpretive signs, including this map, now enhance Hawks Bluff Park, in Batavia, Illinois:

After playing on the swings, the girls set out with Grandma and Agramonte, their Tibetan Mastiff (now 8 months old and weighing 98 pounds):

The girls are on a mission of discovery:

A fresh cicada shell catches their eye:

…as does this beautiful female Tiger Swallowtail Butterfly:

Yucky! A butterfly (probably a Question Mark, Polygonia interrogationis) rests on fresh scat (probably raccoon):

Both male and female Common White-tail dragonflies were present. Male:

Members of the skimmer group, the female Common White-tail lacks the namesake abdominal color:

Collecting sticks, stones, and bugs is fun, too:

A stop at the water fountain before heading home:

Agramonte, Tibetan Mastiff, almost 8 months old:

A combination of hot weather and being “under the weather” have forced me into a couple of weeks of down time. No extensive hikes, no serious photography, although I captured images of several feeder birds off the deck in our daughter’s back yard. Now in Illinois and hopefully nearing the end of encounters with the health care system, I hope to make it back out to Nelson Lake any day now.

Mourning Dove:

House Finch, Male:

Yesterday, during a brief walk with Agramonte in Hawk’s Bluff Park in Batavia, I watched a Cooper’s Hawk bring dinner toward a couple of shrieking youngsters who had already branched and actually sounded as if they were in two different trees. A month ago, before returning to Florida, I had found the general location of the nest, in a tall oak about 50 yards from the bank of Mill Creek. At that time the young must have been very small, as their begging cries were barely audible.

Forced leisure has induced me to revisit some great birding literature on the Web. Here are a few samples:

One of my favorite places to browse also has some of the oldest content. LIFE HISTORIES OF FAMILIAR

NORTH AMERICAN BIRDS

This electronic book collection of Arthur Cleveland Bent’s species biographies is selected from the hundreds that are part of a twenty-one volume series published between 1919 and 1968 by the United States Government Printing Office. I have reprints of over a dozen volumes on my bookshelf at home and really enjoy Bent’s meticulous attention to detail. Sure, Bent anthromorphizes and is judgemental about “good and bad birds.” So much more has been learned about birds in the meantime by “high-tech” researchers, but reading the prose is pure pleasure. The site contains a species index and an excellent search feature.

For example, I entered “Cooper’s Hawk,” and was greeted by this opening paragraph:

“If the sharp-shinned hawk is a blood-thirsty villain, this larger edition of feathered ferocity is a worse villain, for its greater size and strength enable it to do more damage. Furthermore, it is much more widely common during the breeding season, being one of our commonest hawks in nearly all parts of the United States. It is essentially the chicken hawk, so cordially hated by poultry farmers, and is the principal cause of the widespread antipathy toward hawks in general.”

It immediately reminded me of how my grandfather hated “Chicken Hawks,” although he usually was referring to the Redtails that sailed so conspicuously over his flock as they foraged in our joint back yards. I remember seeing a very frustrated Cooper’s Hawk trying to get through the chicken wire that enclosed his pigeon pen, so intent on the pigeons that it ignored my presence only about 10 feet away. I was probably around 9 or 10, but I will never forget the wildness in its hackled stare.

Another noteworthy and respected collection of birding literature that offers a time travel from the twenty-first back into the nineteenth century is available at the Univerity of New Mexico’s SORA Web site: “Classic Ornithological Journals archived and available to all.”

The choice of journals on SORA is almost too good to be true, and you don’t need a subscription or password to access their full content:

Auk (1884-1999)

Condor (1899-2000)

International Wader Studies (1970-2002)

Journal of Field Ornithology (1930-1999)

Journal of Raptor Research (1967-2005)

North American Bird Bander (1976-2000)

Ornithological Monographs (1964-2005)

Pacific Coast Avifauna (1900-1974)

Studies in Avian Biology (1978-1999)

Wader Studies Group Bulletin (1970-2004)

Western Birds (1970-2004)

Wilson Bulletin (1889-1999)

Of course, an excellent addition to the electronic library is ABA’s Birding Magazine collection of back issues to 2001

Another popular magazine, Birder’s World, provides a search box in which you can enter a species or birding location and have access to much of the content of past issues. To help, there is also an index of past issues.

WildBird magazine has archived copies of tables of contents that go back to 2004, but the articles cannot be accessed, and there are no search functions. Likewise,

Male Mourning Dove (L) coos and displays to female: