Posted by: Ken @ 5:47 am

Readers have probably noticed that I take most of my photos in birding “patches” very close to home, mainly in the adjacent water conservation area that we call the West Miramar ESL (for its designation by the South Florida Water Management District as an environmentally sensitive land or area). Rather than chase after rarities, we usually wait for the birds to visit us. Pretty soon we will respond to our own migratory urge and try to catch up with them up north.

We enjoy the birds, but we also like being in the places where the birds are– mostly scarred remnants of former natural beauty, but places where we can briefly ignore the sounds of lawn mowers and leaf blowers and hear splashing on the lake and the songs of cardinals, yellowthroats and towhees. We like getting out early, around sunrise, and walking fast before stopping to watch and listen.

On the first of January this year I reflected on the fact that now I have lived a portion of my life in each of the past nine decades. This does not make me 90 years old, but it means that I was born in the middle of the Great Depression and accounts for my compulsion to get up and out and make the most of every day.

Depending upon the birds to come to us creates a sense of urgency during migration. We must be out there to greet them. Earlier this week we learned we could not predict the arrival of flocks of warblers in our neighborhood. Trying to anticipate the perfect morning for birding during migration, I keep track of the weather radar. So far there has been little correlation between the abundance of migrants in our neighborhood and the density of the flocks that appear on the radar screen.

For example, on April 14 we saw nine warbler species, as reported in our previous blog. That night the radar looked very promising. It appeared that migrating birds had piled up on the northern coast of Cuba and had begun their flight across the Straits to Florida at sunset. We hoped that the next morning would be even better for warblers.

Here is the Key West radar image covering the period between 9:30 and 10:38 PM EDT on April 14th:

Angel and Mariel track migrants on radar in their blog, Badbirdz2. They reported “Heavy Migration Over Florida” and their overnight radar loops documented the continued passage of migrating flocks over south Florida, including our home, into the early morning hours. We got out early, expecting to be surrounded by colorful warblers. I hid inside the “hammock” for two hours, and saw many, many catbirds that may have helped cause the radar echoes, but not a single warbler, or other migrant!

Before Mary Lou abandoned me at the “make-believe hammock,” we had visited the lake at the far end of the unpaved road into our patch, where we found a small flock of Least Terns. A pair of Least Terns posed nicely on a rock:

They flew back and forth in front of us, allowing me to practice taking in-flight telephotos with my new Canon 60D:

The smallest of the terns, the Least Tern has a proportionally long bill and short tail, and in breeding plumage has a black cap and sharply contrasting white forehead:

I caught a Red-winged Blackbird in mid-song, his partly spread wings showing off bright red epaulets:

The light was behind this Tricolored Heron as it watched us warily:

A Green Heron joined the terns along the edge of the lake:

Two days earlier, I was so engrossed in photographing the terns that I forgot a cardinal rule– never take a step without first checking the surroundings. Out of the corner of my eye, I caught the slow movement of a snake, only about three feet away.

It was a poisonous Cottonmouth water moccasin:

Of course I stepped back as the snake coiled into a defensive posture. It opened its mouth and began to regurgitate what looked like the tail end of a siren (a common legless amphibian). This may have been in response to the stress created by my disturbance:

Like cats and other nocturnal predators, all the North American poisonous snakes (except for the Coral Snake) have elliptical pupils. This is an adaptation to night vision, allowing them to protect their sensitive eyes by shutting out almost all the light if necessary:

Snakes are fascinating creatures. Cottonmouths eat a great deal of carrion, and are not aggressive. They are inconspicuous, and about the only way to get bitten is to touch one or step on it unawares. As a sad footnote, when we returned to this spot we found a Cottonmouth, probably this same snake, crushed by boulders:

Yes, it is poisonous, and some guy now thinks he’s a hero, but I don’t think that the world is made any better by senseless killing.

As a kid, I used to step on any ant I saw on the sidewalk, for sport, or maybe to make it rain.

Such a habit may have persisted in my subconscious mind. Several years ago, while leading a group of 8 to 10 year old kids on a nature walk at Rio Grande Nature Center in Albuquerque, I casually stepped on an ant– I must admit it was an intentional act.

One of the kids immediately asked, “Why did you do that?”

“Do what?”

“Step on that ant.”

I could only reply, “It was wrong for me to do that– the ant was minding its own business and wasn’t doing anything to hurt me.”

Why did I do that? It was a simple but profound lesson for me. I had extinguished a tiny spark of consciousness, and my universe had been diminished, be it ever so slightly.

Posted by: Ken @ 12:14 pm

The first time I heard a Florida birder talk about finding birds in a certain “hammock,” I almost wanted to correct him. Up east, the only hammocks I knew were made of canvas and slung between two posts. I thought he meant to say “hummock,” a word that I first heard used by a farmer, who pointed to a hill out in the middle of his hayfield that was too steep to mow and had gone over to shrubs and trees. Of course, I’ve since learned that “hammock” has a very specific meaning in any discussion of Everglades ecology.

From the ground, a hammock indeed looks like a “hummock,” a tree-covered hill that rises high above the surrounding Sawgrass prairie. Hammocks are scattered throughout the Everglades, but they are actually quite level, and only a foot or so above the high water mark. It is the trees themselves that rise up in a graceful mound. In the dry soil, hardwoods of many kinds flourish, draped with ferns and air plants: mahogany, oak, maple, hackberry and gumbo limbo, as well as native palms. Cocoplum, commonly used as a hedge or small shrub in residential neighborhoods, grows to tree size. Hammocks serve as refuges for more terrestrial creatures such as bobcats, panthers and raccoons.

It can be quite cool in the deep shade of a hammock. My only experience in walking through a hammock has been on trails in Everglades National Park. In my neighborhood, the land has been drained and filled, and hammocks are long gone. However, I did find a very lame imitation of a hammock at the edge of our subdivision, where for some unknown reason, the landscapers have allowed trees and shrubs to grow undisturbed.

Here is our little “faux hammock.” Cool and surprisingly not very buggy, it sometimes harbors migrating warblers, vireos and tanagers:

The trees are mostly exotic and invasive Brazilian Pepper, a species introduced and popularized as “Florida Holly” because of its bunches of red berries.

A Blue-gray Gnatcatcher perches on a clump of Brazilian Pepper berries. The thick leathery leaves smell like turpentine when crushed:

Other fruit-producing trees and shrubs I have found in this spot include ligustrum and lantana species, as well as several native Florida Trema (Trema micranthum), - a weedy pioneer tree that is a popular food plant for migratory birds. I discovered that this type of tree was particularly important to the birds that visit here. Hundreds of catbirds were passing through, and they helped clean up the ripe Trema fruit, as the tree continued to produce new green berries.

The berries of the Florida Trema grow in clusters along the stems rather than hang in bunches; its leaves are thin and soft:

This past week we finally had an influx of spring migrants. Here in Florida, spring just sort of creeps up on us just about when we need to turn on the air conditioning and the nights become too hot to sleep with the windows open. As is our habit, Mary Lou and I begin our morning exercise at dawn by walking the unpaved road that leads into the wetlands preserve next to our home. On our way back, after visiting the large lake about a half mile in, we stop at our “hammock,” where I tend to linger and hope for killer photos of birds, sankes, alligators, Bobcats… anything that moves and many things that don’t. Although she is great about putting up with my frequent stops, I understand when she runs out of patience and wants to keep walking.

Previously, we always birded our “hammock” from the outside, but this year I ventured into the depths of the trees and shrubs and was surprised to find quite a nice open area beneath the dense canopy:

Standing quietly in the shade for over an hour at a time, we let the birds come to us. Some look down quizzically to find out who is invading their territory…

…including this Gray Catbird (note the green unripened Trema berries):

…a Common Grackle collecting food for nestlings:

…a White-winged Dove perched in the Trema:

…and a normally timid Common Ground-Dove, a species that never before permitted me to get so close:

Warblers, the stars of the show, paraded before our eyes, strangely silent. Up in Illinois they often sing as they approach their northern destinations, but here in Florida the most I hear from them is an occasional call note: “chip.”

Our first visitor was a male Black-and-White Warbler:

A male Black-throated Blue Warbler plucked a Trema berry:

An American Redstart never sat still more than two seconds, so most of my attempts to photograph it resulted in empty branches. Only after I got home and reviewed my shots did I find this single full-body image:

I spent nearly a half hour trying to get an unobstructed view of a male Blackpoll Warbler, to no avail. Mary Lou got tired of watching me and walked home. After I gave up the chase, it came to me and posed nicely:

While it is considered to be one of the “confusing fall warblers,” the female Blackpoll is quite distinctive in spring:

A male Cape May Warbler provided a splendid view, and Mary Lou can only blame herself for missing it:

A female Cape May Warbler was harder to keep in my viewfinder as it gobbled down the Trema berries:

This was the best portrait I could obtain of a Prairie Warbler:

As a side note, I found it interesting that the old dried Trema berries developed some kind of white powder on them– whether it was powdery mildew or possible scale insects, I don’t know. This past winter, a Prairie Warbler got the white dust on its bill as it foraged among them (Photographed at same location, February 4, 2011):

A Blue-headed Vireo paid a brief visit…

…as did a Least Flycatcher, a species not commonly seen here during spring migration:

A male Northern Cardinal offered me a lucky shot in between the branches of the Trema (note how the berries grow along the stem and ripen at different times, providing a steady supply of food):

It was impossible to overlook the butterflies. Here, a Zebra heliconian sips nectar from a pink Lantana flower:

The shaded Lantana bear pink flowers, while those in full sun tend to be orange, red and yellow. A Julia heliconian visits a Lantana that reaches above the canopy, over 20 feet tall:

Rustling in the leaves underfoot reveals a Brown Anole that scurries up a stem to display his dewlap to a rival:

Posted by: Ken @ 3:09 pm

We got out to the wetlands near our South Florida home just before sunrise this morning. Several mornings, we have seen Bobcats on the trail along the levee, so this is always our first stop. Since the trail is overgrown, we can approach it without being seen in advance. We walk quietly up the levee to the edge of the trail, and Mary Lou looks to the right while I look to the left. As is too often the case, we saw no Bobcats.

This was an earlier Bobcat sighting along the same path:

Light fog reduced visibility, and it did not look like a good time for photography. We continued north about a half mile to the Harbour Lakes impoundment, part of the water conservation area that we call our local birding patch.

Last week we had found a heron there that posed an identification challenge. Living on a lake, we have learned to identify the common herons quite easily, even when they are on the opposite shore.

I had never before seen a heron that looked like this one. It was a plain grayish brown all over, with darker wings, but no other prominent plumage features. Its bill and legs were black, and on our first encounter it was sitting quietly in shallow water at a fairly long distance, about 150 feet:

It was difficult to tell how large the bird was at this distance. I noticed it had a prominent “chin” that extended under the base of its lower mandible. Its neck was very long, and my guess was that it was an immature of some kind, possibly with abnormal pigmentation such as partial albinism or a deficiency of melanin.

I have the Sibley field guide app in my iPod, and I compared it to all the locally common herons and it certainly did not match the plumage of any species I viewed. A disadvantage of this app is that if you wish to compare the plumage of several species you must exit and then select individual species for comparison. Back home, when I thumbed through Sibley’s “real” field guide, this bird’s picture jumped right out at me. While I am familiar with the adults of this species, this was the first one I had seen in this plumage. It was still there this morning.

It was an immature Reddish Egret, and today its actions gave it away, as it engaged in a very characteristic foraging behavior that is quite unique. It chases after fish, willy-nilly, darting this way and that, alternately running, hopping and flapping, changing directions seemingly at random:

It will suddenly stop and shade the water with its wings, either to cut down on glare or to cause fish to seek shelter in the shadow:

The egret was joined by a Tricolored Heron. About 46 inches long (from tail tip to bill tip), the egret is almost twice the size of a Tricolored Heron (which measures 26 inches in length), and the latter is much more slender and has a proportionately longer neck:

The Tricolored Heron is also a very active feeder, but its antics do not quite match up to those of the Reddish Egret:

The Reddish Egret is normally found in salt or brackish marshes along the coast, but immature birds are known to wander into the interior of Florida. We live 18 miles inland, and this was the first Reddish Egret I have seen or heard of in this area. For a slide show that shows both birds engaged in what looks like some kind of exotic dance, click here (best viewed full screen): Dance of the Herons

There was more excitement in store for us this morning, We had two new “first of Spring” arrivals, a Black-necked Stilt:

…and a flock of Least Terns:

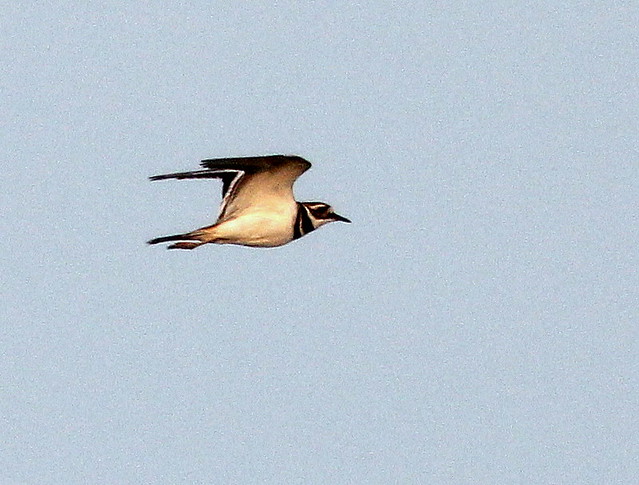

Least Terns have nested on the flat roofs of a nearby supermarket and an elementary school.They are a welcome sign that Spring has arrived. This is not a very good photo, but I find it almost impossible to catch one in flight:

Another treat this morning was finding two adult Bald Eagles roosting in a tree about 1/4 mile to the north. They are probably the pair that is nesting several blocks west of that location (the smaller male is to the left:

Also providing witness to the fact that Spring has surely arrived, a pair of Killdeers were engaged in a courtship ritual. Calling softly, the male (to the left) followed the female closely for several minutes:

Suddenly another male burst upon the scene. He partially spread his wings and expanded his upper black neck band in a threat display, and the males exchanged shrill calls:

The interloper was chased off by the original suitor:

Amid the commotion, the stilt also flew away:

…while a Double-crested Cormorant surfboarded to a perfect landing:

Many people across the country and the planet are monitoring the progress of a pair of Bald Eagles in Decorah, Iowa. A nest camera with excellent video quality is mounted in the nest tree and looks directly into the nest, 80 feet above the ground. As the 35th day of incubation drew near, Mary Lou and I were continually checking the three eggs for signs that an eaglet was pipping the shell.

The first eaglet hatched out on April 2, 2011 (this is a screenshot from the Decorah nest camera):

We have a particular interest in Bald Eagles, as we have been involved in protecting a recently discovered nest in our south Florida neighborhood. Coincidentally, the eaglets in our local nest are just taking their first flights as the Decorah eaglets are hatching. We first became aware of the local pair of eagles when I photographed them mating on the rooftop of a house just across the lake from our home.

Bald Eagles mating, December 4, 2007:

As there had not been a record of an active Bald Eagle nest in Broward County since several years before DDT was abolished in the early 1970s, I reported the sighting on the Tropical Audubon Society’s Web page. A biologist who lived about 1 1/2 miles from our home got back to me with word that she had been seeing eagles in her neighborhood. She had a general idea of where they might be breeding, but was unable to find their nest. By chance, Kelly Smith, a local middle school teacher found the nest in March, 2008. The nest was located only about 150 feet from a busy boulevard in the neighboring City of Pembroke Pines, and it contained one nearly full-grown eaglet.

This photo of “P. Piney One” was taken by Kelly Smith on March 15, 2008 and is reproduced here with her permission:

Residents in the area of the nest had been seeing eagles for at least a couple of years before the nest was “discovered,” but no one ever pinpointed its location and reported it to the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC) which is charged with protecting the eagles under federal and state laws and regulations.

The pair of eagles have returned to the same nest each year, successfully raising and fledging two chicks in 2009 and three in 2010. This past October they again set up housekeeping, and have produced two more eaglets. Since the nest is about 50 feet high in an exotic pine tree with smaller trees blocking most of the view, we only can obtain distant looks. Oh, how we would like to have an eagle nest camera on a par with the Decorah cam! Our local “Pines” nest could kick off the viewing season before Christmas and be followed by shows from more northerly locations.

On December 11, 2008, both adults are shown sitting on the nest, only two days before the first of two eggs was laid::

Local middle school students conducted a nationwide poll that chose names for the two eaglets, “Hope” and “Justice:” They hatched on January 15,2009. Here they are, squabbling with each other at exactly one month of age. Hope, the older and larger, is on the left:

The eagle nest attracted a great deal of attention, and crowds of up to 100 people came to see the antics of the eaglets, causing traffic hazards as they stopped on the roadway and parked illegally.

The Mayor took an interest in the nest, which is located on City of Pembroke Pines property. The media hyped the story, increasing the crowds and the threat to public safety, leading to restrictions for pedestrians and motorists in the area of the nest. The Mayor announced his intention to declare the site a City Bald Eagle Sanctuary, and appointed a steering committee to provide advice on measures to protect both the eagles and observers.

The Bald Eagle Sanctuary Steering Committee embarked on a (so far) unsuccessful attempt to install a web camera. Prospective funding sources evaporated, and the power company backed off from their earlier assurances to sponsor and permit a camera on a pole directly in front of the nest. Likewise, plans for support by the state highway authority to fund a camera fell through. The good news is that the City has amended its planning documents to pave the way for an ordinance that will provide safeguards against disturbance of any eagle nest in the city.

The Mayor views the nest with a reporter and a news photographer:

I photographed these three eaglets on March 2, 2010. The Middle School students’ poll resulted in them being named Chance, Lucky and Courage. All three fledged successfully:

The eagles returned in October, 2010 to refurbish the nest, and eggs were laid around December 11. ( * See end note about how we estimate the time of egg laying and hatching). On January 23, 2011 at the age of about 9 days, this chick was first seen, peering over the nest rim:

Here, it waits as its parent tears off a bit of food. A younger sibling has not yet been visible from the ground:

The Parent eagle feeds the chick :

This was about as good a view we could get from 150 feet. Plans for a nest camera did not materialize:

Here is the older of the two eaglets, on February 3, 2011. Much of her natal down has already disappeared:

At one month old, on February 15, 2011, the down has been reduced to a fuzzy cap:

Less than two weeks later, on February 27, the eaglets look almost as large as adults. We call them “P. Piney Seven & Eight.” Bald Eagles exhibit sexual dimorphism that starts when they are nestlings, with the females usually considerably larger than males. PP 7 is the larger and is presumed to be a female:

At two and a half months of age on March 23 they are exercising their wings, preparing for their first flight, which usually occurs when they are between 10 and 12 weeks old. PP7, on the right, has more white underneath than her younger brother:

On March 30, 2011, we found PP8 alone in the nest; PP7 had flown off, but returned within three days to be fed:

On March 30, PP8 was “helicoptering,” hovering in place up to a foot off the ground:

Here, on April 3, 2011, PP7 roosts in a tree next to the nest. PP8 is flying on branches in the nest tree but has not been observed in free flight:

* In estimating the timing of the laying of eggs and hatching of the eaglets, we must depend upon clues from changes in the behavior of the adults. The onset of incubation coincides with the laying of the first egg, which is when we suddenly see one of the pair down deep and immobile in the nest. Hatching is a time of excitement, as the parents shift position frequently, peer down into the nest, and they start bringing in prey and tearing off bits to feed the tiny chick. The adults also sit a bit higher in the nest after the first egg hatches, supporting themselves on their wings to form a “tent” to shelter the chick and yet provide warmth to any eggs that have not yet hatched. Volunteer nest observers share their sightings in the Pembroke Pines Eagle Nest Watch FORUM at this link.

Yesterday, a drama played out before our eyes. We had the Decorah Eagle Nest Camera on the screen of our laptop in the kitchen while preparing dinner. (In case you have been living on another planet and are not responsible for one of over 11 million visits to the site, this nest, located 70 feet above the ground next to a fish hatchery in Decorah, Iowa is monitored by a video camera 24 hours a day. The camera looks down into the nest and provides tack-sharp streaming images of a pair of Bald Eagles during the breeding season. As of this writing, two of the three eggs has hatched, the first on April 2nd and the second only yesterday, April 3rd.)

Yesterday afternoon I happened to look at the screen just as the male eagle got up from brooding the two eaglets and the remaining egg. He fed the chicks, and then seemed to be cleaning stuff out of the nest, when he either mistakenly picked up the older of the two chicks by its leg, or the little chick grabbed unto the adult’s bill. Reflexively, the adult bird shook its head and tossed the chick, which landed at the periphery of the nest.

I immediately started capturing screen shots.

The male parent’s action was entirely accidental, I’m sure. Luckily, larger branches form a sort of fence around the nest that kept the downy eaglet from falling to the ground. The male looked on helplessly as his little chick cheeped and tried unsuccessfully to climb up the wall into the nest cup.

The egg and the younger eaglet are together inside the nest

cup, while the other eaglet is separated from them by the wall of the

nest cup, down the deep slope to the right of this image:

Repeatedly, the chick failed in its attempts to climb up over the edge of the nest cup, falling back each time. Despite its constant distressed cheeping, the male parent stared at the chick, but appeared to ignore the plight of the little chap:

Finally, the female (foreground) arrived to take up brooding and incubation duties. The eaglet was still out in the open and immobile, exhausted by its efforts and possibly feeling the effects of exposure to the cold:

At first, the mother eagle seemed oblivious to the plight of her chick. As eaglets are incapable of regulating their temperature at this age, it faced certain death from hypothermia if it was not quickly returned to the shelter of its mother’s wings:

The female parent started nibbling on the edge of the nest cup, as if trying to clear a path, then she reached out and gently rolled the chick up the incline and into the nest cup:

It had seemed like an eternity that the baby eagle had been stranded out in the cold, but it was only for about 15 minutes. After warming up for an hour or so, the eaglet begged vigorously and ate heartily:

Both chicks had a tug of war over one chunk of meat:

Now watch the mother eagle rescue her baby in real time (You Tube video by Eagle Cam Fan):