Soaked by the welcome rain, “Justice” (the name given to the younger and smaller eaglet) is now about 8 weeks old:

It’s been said that the last thing that science will ever discover is what it is about. Seeking truth, researchers use the “scientific method.” We may take certain things for granted, but if we apply the scientific method to our assumptions and intuitions we may reach exactly opposite conclusions.

Even after I learned to say a few hundred words, I probably still believed that the earth was flat, just as did some very sophisticated adults not too many centuries ago. Before migration was discovered, a plausible explanation for the disappearance of some birds during the winter was that they plunged into the sea to sleep, emerging the next spring. Many other beliefs about the behavior of wild creatures still lack testing and proof.

“Hope,” the larger sibling, is about 5 days older than “Justice.” She appears to have more prominent white markings on her chest:

A parent brings in a prey item, which appears to be a fish, and offers a portion:

“Justice” waits patiently while his older sister (partially obscured behind the tree limb) is fed:

So it is with the newly urbanized Bald Eagles of Florida. As they adapt to the proximity of humans and their activities, what are the limits of their tolerance to disturbance? Certainly (we assume), there must be a limit, an end point at which they will completely avoid us. Walk up to an eagle in the wild, and when we get within a certain distance, it will first show signs of discomfort or anxiety that we might detect. Its eyebrows cannot wrinkle into “worry lines,” because the bony structures of its skull give the eagle a permanent fierce frown. It may exhibit other signs of intolerance– first by staring at us intently, then shifting its posture in preparation for flight, and perhaps by vocalizing, or even defecating to make itself lighter. Then it will fly from its perch, removing itself from the perceived threat. We could measure these behaviors in large numbers of rural and urban eagles, and perhaps note a difference between their reactions at various distances from the intruder.

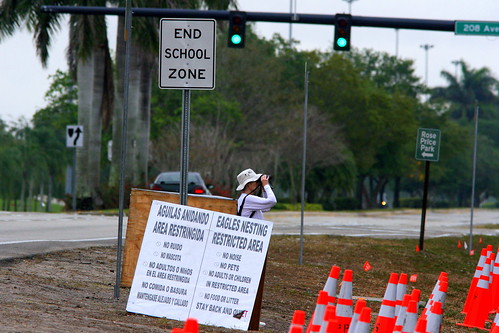

Mary Lou observes the two chicks from the viewing area, at the edge of Pines Boulevard:

The Pembroke Pines Bald Eagles have already established an “end point” of sorts, by selecting a nest site only about 200 feet from the edge of a busy State highway, with homes, a high school and even a police shooting range nearby. Seventh grade science students at Silver Trail Middle School postulated that the rhytmn of human activity provided a starting point for investigation. Traffic density in front of the nest varies by time of day and by day of week. Can the behavior of the eagles be measured and then correlated with the pattern of vehicular traffic? Anticipating that traffic density may change the habits of the eagles, which behavior(s) indicative of the birds’ anxiety should be observed and recorded? How might traffic density at the moment of such observations be classified?

The students selected the distance of adults from the nest as a relatively easy variable to measure. They chose three variables: “On the nest, in sight of the nest, or not in sight.” This could be a significant factor in nesting success, for if the birds avoid the nest they may not provide sufficient care for the eggs and nestlings. This could even result in abandonment of the nest. For traffic desnsity they decided upon criteria for “Light, Medium and Heavy.” They also selected a 20 minute duration for each set of observations, recording them once each minute. They hypothesized that the eagles would spend less time near the nest during periods of high traffic density.

Of course a study of this sort, if it were to reach valid conclusions, would have to be carried out by an army of researchers at dozens of eagle nests in comparable locations, using randomized observations each day throughout the nesting season. In fact, there are probably few (if any) other identically situated Bald Eagle nests in Florida. Lacking funds, who would volunteer to undertake such an effort?

Out of necessity, the students had to confine their study to non-school hours and within the time constraints of their science curriculum. Their teacher, Kelly Smith, summed up the results of their study rather succinctly. After collecting and aggregating their data, the students

Though their findings were contrary to their original hypothesis, the students know not to draw a scientific conclusion. They did come up with an interesting new idea. Might disturbance actually trigger protective instincts that cause the eagles to spend more time at the nest? The class has been designated to receive a grant from the School District to continue their studies in the next nesting season, when, hopefully, the eagles will return. It would expand the scope of their research to include satellite tracking of a fledgling.

After feeding the chicks, the adult perches to dry its wings atop a Melaleuca snag just to the west of the nest tree:

The dreary skies and rain created problems with photography, but this sepia-toned image was nonetheless striking: