Review: The Crossley ID Guide: Eastern Birds

Richard Crossley

Princeton University Press

When I first picked up this book, I was surprised at how hefty it was. Like so many other birders, I saw the pre-publication press releases and the author’s video preview. The computer screen images of birds in multiple poses and at various distances were very appealing. I did not give much thought to the fact that displaying 640 of these plates in a readable format would require lots of large pages. Indeed, the book measures about 8 x 10 inches and its 544 high-quality heavy pages produce a volume that is 1 1/2 inches thick and feels like it weighs about 4 pounds. This is not a field guide, nor is it meant to grace the cocktail table. Rather, it is a unique tool for learning how to better identify the birds. It includes an unprecedented 10,000 individual bird images, all from Crossley’s own collection, except for a handful contributed by other photographers.

Crossley’s departure from the normal field guide format starts just inside the flexible front cover of the first page. A simplified display of its contents, two pages wide, depicts thumbnail-sized unlabeled photos of representative species, collected into two major groups: Waterbirds (Swimming, Flying and Walking) and Landbirds. The Landbirds are subdivided into Upland Gamebirds, Raptors, Miscellaneous Larger Landbirds, Aerial Landbirds, and Songbirds. This is followed by a 16 page “Quick Key,” a surprisingly useful table of contents that builds upon the same classification scheme. Each page of the Key includes 3 to 7 rows of proportionally sized color photos of all the more widely distributed species addressed in the book. Each photo is tagged simply with a four-letter “bander’s shorthand” species code and a page reference, an early clue that space will not be wasted on unnecessary narratives.

This is a book designed to be absorbed visually rather than to be read from cover to cover. The order of species is logical, user-friendly, and should appeal to birders at all levels of experience. Rapid advances in scientific understanding of the relationships between species often results in them being reordered; guides that adhere to a strict taxonomic classification can be outdated before they are published.

Resolving not to go directly to the plates (though I admit to a few early peeks), I started by reading the Introduction, twelve pages of dense text, interrupted by four color plates on bird topography. It is very informative, and provides suggestions on how to use the Guide, and “How to be a Better Birder.” The latter section contains much interesting and useful information about avian topography, molt and terminology. The topography plates are particularly well executed. Instead of the generalized illustrations so commonly seen in field guides, Crossley uses several large format color photos of birds from the various groups to better point out their unique plumage and anatomic features.

The text becomes more sparse and concise as we move into the major groups of illustrations. There are general notes about behavior traits that help locate and distinguish between species. For example, Crossley points out the importance of scrutinizing every member of a flock of geese, as they may act as “carriers” of less common species. In the case of flocks of shorebirds, their tendency to group together by species may call attention to a “loner” that may be particularly interesting. The section on raptors addresses issues of plumage variation peculiar to some species and related to age in all. Crossley suggests that variations in color among sandpipers might best be regarded as shades of gray– he advises us to learn to “think in black and white.”

Turning to the plates, they can be a bit overwhelming at first, but they follow a general pattern. Birds in the foreground are nearer and larger. Variations in appearance related to sex and age, as well as many “in between” plumages are pointed out here. In the background, the birds appear smaller and more distant. Labels are generally not needed beyond pointing out major features such as sex and subspecies differences, but minor variations between individuals related to age and stage of molt are often self-evident and do not require explanation.

In comparison to guides that have preceded this book, the Crossley ID Guide stands alone in depicting a much greater variety of appearances that may relate to such factors as postures of a bird, or the different positions of its wings in flight, as well as lighting, distance and sometimes its flocking and social behaviors. We see dense flocks of feeding Snow Geese, resting Sanderlings… birds doing what birds do: sleeping, preening, sunning… closely packed rafts of Common Murres and Greater Scaup… Upland Sandpipers dispersed singly in a short grass prairie… Cave Swallows swarming around their nests along a beam under overhanging eaves of an open livestock shelter.

Aside from the visual delight of the plates, Crossley’s captions are packed with identification tips that address not only size, shape and plumage, but also voice, behavior, and similar species.

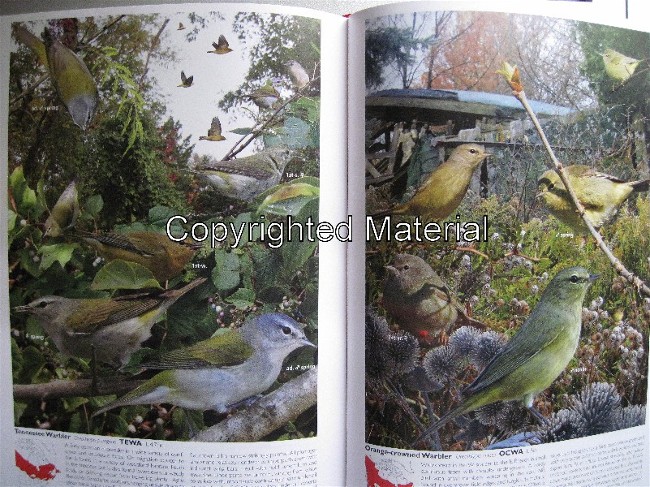

For example, facing plates of the Tennessee and Orange-crowned Warblers provide very useful comparisons between them. What birder has not had to deal with fleeting looks at one of these species? They share some similar and variable features.Their diagnostic undertail coverts are not always evident as they move rapidly through trees and shrubs. In addition to providing a large number of photos of both species in varied plumage, Crossley points out behavioral clues, such as the Tennessee Warbler’s tendency to occur in flocks and often hang upside-down in search of prey, in contrast to the more reclusive and often solitary Orange-crowned species, with its robust and longer-tailed appearance.

Because of their close taxonomic relationship, traditional guides also place the Tennessee and Orange-crowned Warblers next to each other. However, they may show only two or three examples of typical plumage forms for each. For the Tennessee Warbler, Crossley’ Guide displays eight views of perched and four more of flying birds, showing us four distinct plumages as well as typical postures. Six recognizable photos of the Orange-crowned species include variations of three different plumages.

On the other hand, less-experienced birders will welcome the fact that plates of the somewhat similar Blackpoll and Black-and-white Warblers occupy facing pages. Since these two species are not as closely related, other field guides that follow the conventional taxonomic order may separate them by two or more pages of other species. Conveniently, Pine and Bay-breasted Warblers, whose similar appearance may pose a challenge even to the most experienced birders, are located in the two pages just before that of the Blackpoll, with which either might be confused. In the text, plumage differences are analyzed in detail.

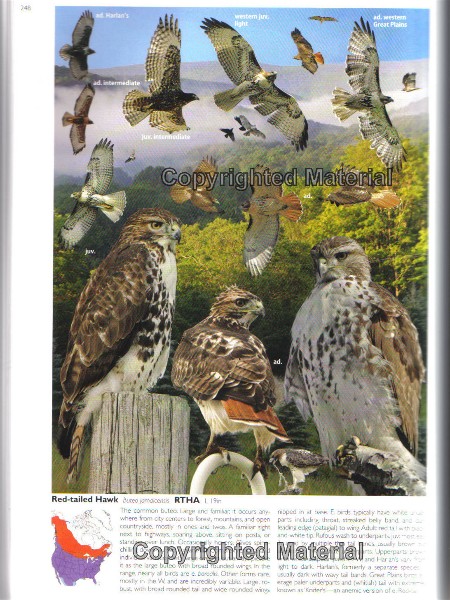

There are several species that exhibit a great deal of variation. The Red-tailed Hawk is one of them:

I compared Crossley Red-tail images and text with those in Sibley’s Guide to the Birds of Eastern North America. The former has 18 images of Red-tails, including flight shots of Harlan’s and western forms. The Crossley text has quite a detailed discussion of the various plumages. Sibley includes 33 images of this species over a two-page spread, including 5 of the dark morph, noting that it is very rare in the east, and 3 of the uncommon Harlan’s, morph. Arguably, Crossley falls a bit short in graphically illustrating the colors, but does better in showing this Buteo’s appearance in flight.

The Savannah Sparrow is another species that shows plumage variation in eastern populations. Crossley provides 10 images, 5 of which are in large enough format to see the birds’ lores. While the amount of yellow seen in the field may vary, it can be a useful feature in identification. None of these excellent images, in varied poses, show yellow lores, but their value in identification is mentioned in the text, along with is a detailed discussion of the plumage, especially the bird’s breast streaking. Sibley has images of 8 Savannah Sparrows, with the amount of yellow varying from none in the Ipswich to quite bright in one. The latter are accompanied by excellent plumage and behavioral descriptions. In both of these examples, Crossley provides large images and very pertinent habitat settings, not possible in the more sparse format of a field guide.

In a departure from the pattern of showing multiple views, an unaccompanied Black Rail lurks furtively in the darkness among the reeds. No open side-on photo, no flight shot– yet a view much better than even those birders lucky enough to have seen one might have wished for. This is the author’s own prized photo– suffice to say it is the only one of this species in his collection (or did he deliberately show this bird, alone and secluded?).

Then there are a few of those delightful and whimsical presentations, such as that of Least Terns swarming around a Cape May lifeboat pulled up on the shore. Comparing the Crossley ID Guide to any field guide is somewhat like comparing apples to oranges. One is not better than the others– the important point is that the book I am reviewing is different… unique, and deserving of a place beside any birder’s easy chair.

Richard Crossley maintains a website with his blog that provides updates and corrections (of which there were only a handful). As necessary, he also elaborates on the captions in the book. I will admit to one disappointment I initially felt after I opened this book. Having watched the promotional video and rejoiced in the brilliance of the screenshots of several plates, I found many of the paper versions of the plates to be quite somber. Sometimes I wished for more light or more detail – even wanted a few of the distant birds to be more clearly recognizable. Some birds were hard to find or partially hidden behind foliage. Wouldn’t this book look better on a computer screen?

This issue is addressed in Crossley’s Introduction: “Just as in real life, the harder you look, the more you will see.” Although an e-book edition would be splendid, I’m pleased to feel the heft of this volume and leaf through its contents. My eyes can scan back and forth between facing and adjacent pages, and down to the text below– and back to a plate to look for that elusive sprite hidden in the shadowy underbrush, “just as in real life.” Being out there sure beats squinting, scrolling and searching.