Avian Architecture: How Birds Design, Engineer, and Build

by Peter Goodfellow

Princeton University Press, 2011

What started my fascination with birds? When I delve deeply into the recesses of my memory, I find no sudden epiphany. I recall looking out the back window of our second story apartment on to the flat roof of the dry cleaner’s store, where a nighthawk was sitting on its eggs. My father had discovered it and pointed it out to me. It was interesting to see that the eggs were laid directly on the roof pebbles, without any semblance of a nest. A few days later, the eggs suddenly disappeared. In their place, unbelievably well-camouflaged, were two chicks. Knowing the date we moved away, I was no older than four years. It sticks in my memory, but did it light a flame?

Perhaps a year or so later, when visiting my uncle in a seminary in Ossining, New York, I came across a compact little nest, low in a hedge. Its lining consisted almost entirely of horsehair, and contained tiny spotted white eggs– three, I think. Two small brown birds scolded anxiously as I peered down into the nest. On a subsequent visit I found the nest to be empty, but in perfect shape. I carefully removed it from its attachments to the twigs and put it up behind the rear seat of the family’s 1937 Ford sedan, oblivious to the prohibitions of the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918. It was a work of art and a treasured possession. Over time, much of the straw fell away, but a perfectly pressed cup of horsehair remained.

Later, I learned that the tiny brown birds that wove the beautiful little horsehair nest were Chipping Sparrows. The criminal nature of my act was exposed when I displayed the nest at a Cub Scout meeting. In the meantime there had been other discoveries– Barn Swallows and robins gathering mud in puddles along the road, a Blue Jay whose entire nesting cycle unfolded in a tree only a few feet from an upstairs window…

…the unforgettable fire in the piercing yellow eyes of a Brown Thrasher whose nestlings I dared approach (Kane County, Illinois, May 28, 2010):

Nest structure ranges from the simple to the sublime–

American Oystercatcher nest (Brigantine, New Jersey, May 11, 2007):

Killdeer nest (Batavia, Illinois, May 12, 2009):

Bald Eagles on nest (Pembroke Pines, Florida, October 5, 2011):

Baltimore Oriole male inspecting his mate’s weaving of the foundation for their nest– or is he doing it himself? (May 9, 2011, Kane County Illinois):

As interesting and varied as bird nests may be, they only provide hints about their creators. A Mourning Dove nest can be so flimsy that the eggs may be visible from underneath. Yet, I once watched as a male Mourning Dove collected short lengths of twigs and brought them up to the female who was constructing her nest in a Cottonwood. She inspected each offering, turning the stick in her bill. Almost half the time, she discarded the gift and it fell to the ground. Her critical eye should have resulted in a durable masterpiece of avian architecture, yet a week later, after a rain storm, the nest was gone.

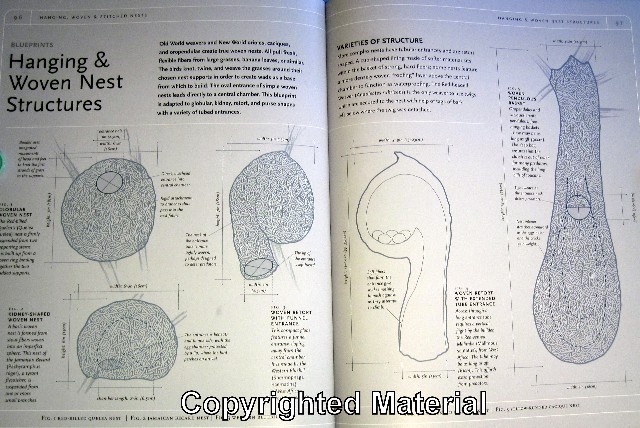

Goodfellow’s Avian Architecture is not only about structural diagrams and blueprints, though it goes into great detail in chapters about nine general types of nest construction, from simple scrapes, holes, platforms, cups, mounds and domes to intricately hanging and woven ones. There are also chapters on aquatic and mud nests, colonial and group nests, as well as intriguing descriptions of courts and bowers, and even edible nests and food stores.

Here is Goodfellow’s set of “blueprints” that introduce the chapter on woven nests, illustrating a variety of styles:

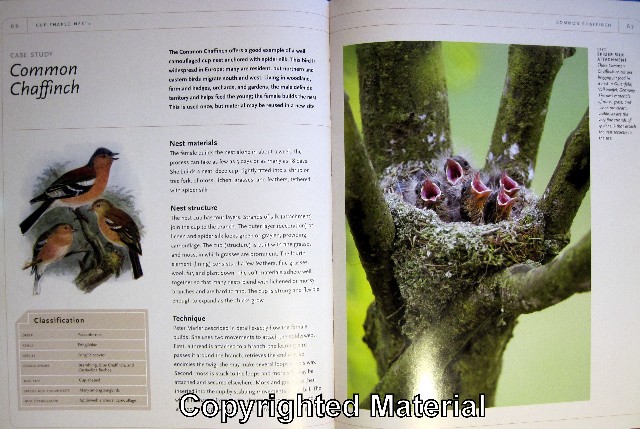

Each chapter discusses construction materials, but most of the book is devoted to case studies of individual species. The representative case studies address where and how the birds construct their nests and the unique features of each. Behavioral traits, breeding biology, habitat and conservation issues are detailed. Global in scope, the book provided me with much new and interesting information about unfamiliar birds.

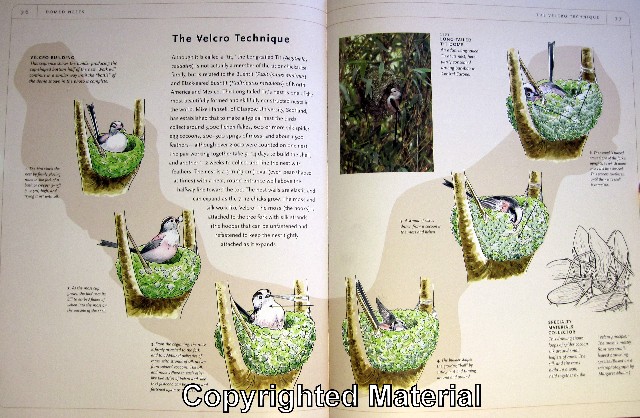

I did not know that birds actually invented “Velcro.” The same system of hooks and loops is used by several species to attach their nests or hold them together. The Long-tailed Tit builds its domed nest by creating loops of silk unwound from spider cocoons and fastening them to sprigs of moss. The selected moss leaves are just the right size to interlock with the silken loops. The attachments can be disengaged and repositioned to accommodate the growth of nestlings.

In each chapter, for a representative species, the author provides a very detailed and illustrated example of the steps involved in construction of the particular nest type, from beginning to end. Whether the bird is unfamiliar or one that is commonly encountered, these contain many interesting facts.

In the chapter on domed nests, the Long-tailed Tit’s construction methods are presented sequentially:

The Sooty-capped Hermit and the Common Chaffinch also use a similar technique. Two page case studies of selected species reveal many other interesting facts:

I learned that one of the largest nests of any bird species is that of the Social Weaver– a “condominium” that begins with a platform roof and includes up to a hundred separate compartments, individually built and occupied all year long. All residents share responsibility for maintaining the roof.

Nests are generally constructed from locally available materials, so they reflect adaptation to a wide range of habitats. The flamingo creates a trough around the perimeter of its nest site as it removes mud for its construction, while the Black Wheatear must utilize stones gathered from the high and treeless rocky slopes of the Atlas Mountains of Spain. It carries the stones, one at a time, to its nest site. Amazingly, we learn that this 1 1/3 ounce bird is somehow capable of moving rocks weighing as much as 10 ounces. Another example of the use of rocks in nest construction is that of the Horned Coot, which creates its own artificial island by piling stones into a cone up to 13 feet wide and three feet high.

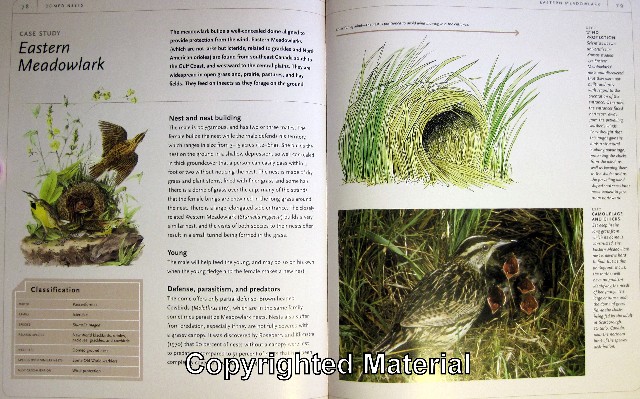

The Eastern Meadowlark weaves fresh grass stems into the structure of the domed roof of its nest:

:

I have seen Northern Goshawks and Bald Eagles bring fresh green leaves to the nest. Other birds commonly incorporate greenery into nest construction. Whether it serves a function such as camouflage or pest deterrence, or is merely decorative is the object of speculation. I was a bit disappointed that the book’s index did not have an entry for green leaves or foliage, nor one on camouflage despite providing several pertinent examples in the text. Neither are there entries for vermin or mites, though the subject comes up a number of times.

The relatively brief index addresses mainly common and scientific species names. While this is a minor drawback, it somewhat limits the reader’s ability to search the text for some common elements in techniques and construction. . For example, when I wanted to find all references to the use of spider web or silk I found only three citations. One discusses the strength of this material in the section on hummingbirds’ nests, and the other two refer to its use by the Common Chaffinch. Yet, the book has other very pertinent descriptions of how birds use spider silk. For example, the Common Tailorbird utilizes spider and lepidopterus silk, as well as plant down, in attaching its rainproof nest under an arching leaf.

Also not indexed is a particularly intriguing method by which the Sooty-capped Hermit hangs its nest from a single “cable,” comprised of many strands of spider silk, which is attached to the edge of an overhead leaf. Since the nest could swing precariously and even tip over, this hummingbird adds a “tail” of spider silk cable beneath the nest and weighs it down with pellets of mud. The weighted tail serves as a counterbalance that keeps the nest from spilling out its contents.

Construction materials such a mud and silk are sometimes cross-referenced, but moss, hair, feathers, rocks or stones are not. However, the case studies provide interesting examples of specialized use of these components.

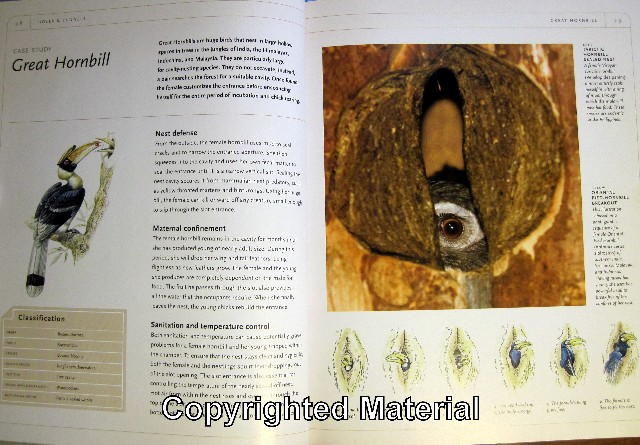

The female Tarictic Hornbill uses mud to seal herself into a brooding chamber for many months to lay eggs and rear young until they are completely fledged, depending upon the male to feed her and their offspring:

The final two chapters of Avian Architecture go beyond descriptions of the nest as a structure in which eggs are laid and young are reared. There are extensive and detailed case studies of courts and bowers, and the final chapter treats edible nests and food storage methods.

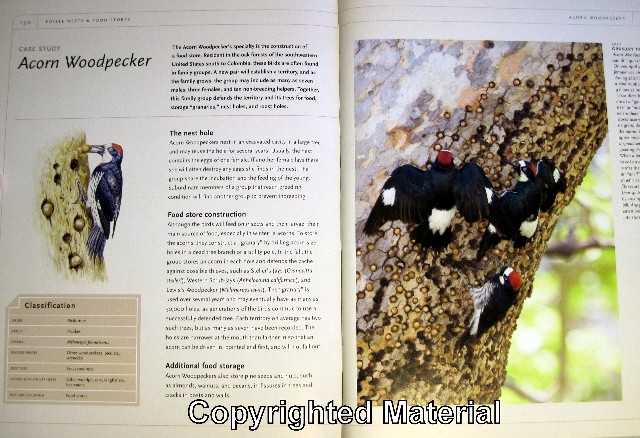

Studies of the Yellow-bellied Sapsucker’s technique for extracting sap and assuring its free flow, and the Acorn Woodpecker’s method of storing acorns and are especially interesting:

.

Avian Architecture is an entertaining and informative resource for anyone interested in the great diversity of bird nests, and the what, why and how of their construction.