Posted by: Ken @ 2:09 pm

We followed our recent trip to our son’s family home in the Texas Panhandle with a short visit to Albuquerque, where our main objective was to see the rosy-finches at Sandia Crest.

There are many great birding spots in and around Albuquerque. Judy Liddell and Barbara Hussey described them beautifully in their recently released book, Birding Hot Spots of Central New Mexico (See my review here). We only had time to bird a few of them. The City of Albuquerque manages an impressively large number of dedicated Open Spaces.

On our first full day, driving from our lodging in Albuquerque to Sandia Crest House, we encountered rain and low clouds as we ascended the east side of mountain. Since we knew that the temperature at the tip was in the twenties (F). we turned around and birded Tres Pistolas (Three Gun) Canyon.

This unimproved Open Space is just off I-40 in the southern foothills of the Sandia Mountains. This photo illustrates the vagaries of mountain weather. Although the sky is blue here and the temperature is in the mid-forties, it is snowing atop the mountains just a few miles beyond.

On the dirt road leading to Tres Pistolas, we encountered this Ladder-backed Woodpecker, busily foraging in a Cholla cactus.

We saw several Townsend’s Solitaires.

A feeder in the residential area next to Tres Pistolas was remarkably productive. Here, from left to right, a Pink-sided and a Gray-headed Junco, two subspecies of the Dark-eyed Junco, share a meal with a male House Sparrow.

An Oregon Junco also visited the feeder.

A feisty Pine Siskin squabbled with a Gray-headed Junco as a White-crowned Sparrow looked on.

From there we drove down to the Rio Grande Nature Center, where I had been a volunteer docent for eleven years, leading bird and general nature hikes. We parked and immediately walked over to the blind at the east end of the parking lot. We saw several Hooded Mergansers.

Inside the Interpretive Center, we were delighted to see our old friend, Sondra Williamson. Sondra was sitting on the couch in front of the big picture window that overlooks the pond, pointing out and identifying the ducks for visitors. A Ring-necked Duck and a Lesser Scaup provided an opportunity for her to compare their features.

There were several pairs of American Wigeons…

…and a spectacular male Wood Duck, roosting next to the pond before taking a swim.

A female Belted Kingfisher hunted from a perch on an island in the pond.

A Pied-billed Grebe flapped in place.

On our final full day, we again visited Sandia Crest, then explored the western foothills of the Sandia Mountains. Lomas Canyon Open Space provided a nice view of Albuquerque, but was not very birdy.

Embudito Canyon Open Space, not far away, offered a wonderful contrast. It was a bit greener than Lomas. There had been recent reports of a Golden-crowned Sparrow as well as Canyon Wrens.

As we entered the gate at Embudito, we were greeted by at least a half dozen Black-throated Sparrows.

Western Scrub-Jays were common.

Although they can be elusive, Canyon Towhees were abundant and out in the open.

Curve-billed Thrashers sat atop the tallest Cholla branches.

A little White-tailed Antelope Squirrel eyed us anxiously.

A Rock Wren scolded.

Time was running out, as we had a dinner date with some old friends and neighbors. We found neither the Golden-crowned Sparrow nor the Cactus Wren, though we did see a fresh nest belonging to the latter.

Unexpectedly, a Rufous-crowned Sparrow made an appearance. We had great binocular views, but I did not get very good photos.

Posted by: Ken @ 8:52 pm

This past week, it may have been just a coincidence, but a cormorant and a stork were feeding quite close to each other at the corner of our lake, in the yard next door.

Double-crested Cormorant:

It is possible that both birds derived mutual benefit, as the stork might have caused larger fish to move away from the shore into deeper waters where the cormorant (a sight feeder) could more easily catch them. The stork might benefit because smaller fish may have been driven closer to where the stork (a tactile feeder) could clamp its jaws when they came into contact with its beak. Note also how the stork stirs the water with one foot while holding its wing up to shade the water around its bill. Its “bubble-gum pink” feet may also resemble worms to attract the fish. As I have discussed in earlier posts, the water level is critical to the success of the stork’s feeding technique. It must be at least halfway up its bill, but cannot be deeper than its eyes.

Wood Stork:

Small fish are believed to seek shelter in the shade. Herons are sight feeders, and some (such as the Tricolored Heron and the Reddish Egret) commonly use this same tactic, in order to cut down on reflection and also possibly concentrate prey in the shadow of its wings. (DISCLAIMER– I had to edit out a beer can that occupied the bank just in front of the stork’s bill.)

Here are examples of a Tricolored Heron and also an immature Reddish Egret using their wings to shade the water in front of them:

The Reddish Egret even created an “umbrella” that completely shaded its body:

Earlier this year, I documented the varied reptilian fare of a stork, an ibis and a Great Egret (see: White Waders 3, Herps 0). I observed a stork as it captured a frog– to me, it appeared to actually strike out and grab the amphibian, but perhaps its bill encountered the frog randomly and its capture was a reflex action. In this case, the stork was hunting alongside a Great Egret. White Ibises, also tactile feeders, are not as sensitive to water levels. Here, they are probing in the moist soil in our lawn at the lake’s edge. I have seen them chase down snakes, lizards and insects, so they can use vision in acquiring prey.

Ibises often forage in groups, and this likely improves their hunting success:

You may be interested in my post Sharing the Table: Commensalism. In ecology, commensalism is a class of relationship between two organisms where one organism benefits but the other is unaffected. There are three other types of association: mutualism (where both organisms benefit), competition (where both organisms are harmed), and parasitism (one organism benefits and the other one is harmed).

Commensalism derives from the English word commensal, meaning “sharing of food” in human social interaction, which in turn derives from the Latin cum mensa, meaning “sharing a table”. Originally, the term was used to describe the use of waste food by second animals, like the carcass eaters (such as vultures and hyenas) that follow hunting animals but wait until the latter have finished their meal.

Next to Chapel Trail Nature Center near our Florida home, Cattle Egrets cluster around cattle, reaping the benefits of their association as the bovines attract insects and also stir them up as they feed:

Also in our back yard lake, a Great Egret and a Wood Stork mutually benefited as another Double-crested Cormorant fished just offshore. Fish, frightened by the activities of the cormorant, fled in all directions. They blundered into the waiting open jaws of the stork as the tactile feeder waited blindly until sensing the hapless fish that bumped into its bill:

Three years ago I described the behavior of this Tricolored Heron, that associated with a group of Red-breasted Mergansers. All moved around the perimeter of our lake. Sometimes the heron seemed to be following the mergansers, but at other times the heron appeared to attract them by finding fish first.

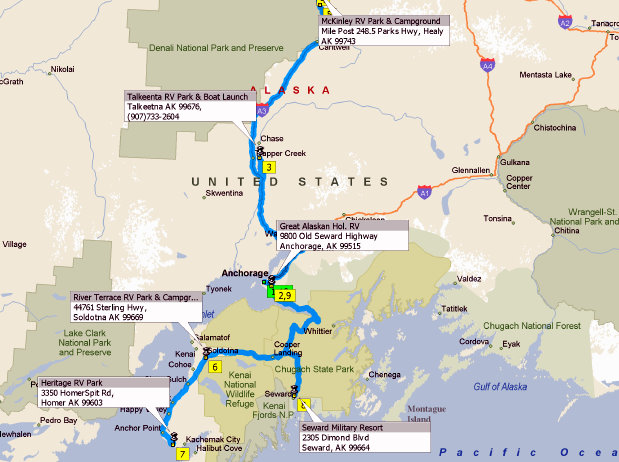

After an all too brief visit to Denali, we set out on a rather daunting 400 mile drive south to the Kenai Peninsula. I learned from the locals to pronounce it “KEEN-eye,” rather than “ken-EYE.” Our daughter and son-in-law shared driving duties with me, which contributed to a much more relaxing experience. Early in the day, we encountered some rain, the only daytime showers we had during the ten days we spent in Alaska. This is a continuation of the narrative of our Alaska journey, which begins at this link.

Retracing our path to Anchorage, we followed Alaska Route #1 south and then eastward as it followed along the shore of Turnagain Arm. This part of Cook Inlet gained its name because early explorers, in search of the Northwest Passage, found this long eastward extension of the Inlet to lead only to a river. Frustrated, they had to turn around again. The road follows the Alaska Railroad, which opened up the Kenai Peninsula to travelers.

Here is the route we followed:

In a past visit to Alaska, Mary Lou and I had watched a pod of Beluga Whales feeding right along the highway, but this time the tide was so low that the mud flats extended as much as a quarter mile out from the shore. Tidal fluctuation is extreme, averaging about 25 feet. It was just past ebb tide, and at one point we saw a rather violent wall of water moving rapidly in across the flats as the tide started rising..

Reaching the end point of Turnagain Arm, the highway doubles back to the southwest through spectacular mountain ranges of Chugach National Forest, joining Sterling Highway near Cooper Landing. The road then enters the huge Kenai National Wildlife Refuge, and roughly follows the Kenai River as it courses towards its mouth at Cook Inlet on the west side of the Kenai Peninsula.

After driving about eight hours, we reached Soldotna, where we camped at River Edge RV Park, on the Kenai River. This section of the river is famous for its salmon runs, which peak around the beginning of July. Fishermen flock to the area and RVs clog all the campgrounds. We found it almost empty, so we had our choice of parking locations.

We took a space right beside the river. Wooden steps lead down the steep bank to a boardwalk that extends about 100 yards along the water’s edge:

Our daughter and her family wasted no time getting down to fish for Dolly Vardin and Rainbow Trout. Naturally, I found time to bird when I wasn’t helping the girls keep bait on their hooks and untangling their fishing lines. The older (seven years old) granddaughter caught the first fish, a 2 inch minnow.

Graci was very proud of her catch:

We saw lots of eagles. This is part of a sequence to show a Bald Eagle landing in a tree on the other side of the river:

Under rather heavy overcast, the Arctic terns were flying by non-stop and usually distant, so my shots all came out either blurred or soft

Since we were in Alaska during the Summer Solstice, the days were very long. The sun didn’t set until after 11:00 PM and rose around 4:00 AM. The sky remained bright and blue all night. We stayed up late and it took us a few days to adjust our sleeping habits. I got out early to look for land birds around the campground.

I found a small flock of Boreal Chickadees. They moved fast, and it was difficult to keep them in view:

This little one looked very scruffy, as if ready to molt:

My iPod Touch got fried the first night of our trip, when I charged it with a third-party AC charger . It contained the big Sibley Field Guide app, so I had no help in identifying unfamiliar birds. I also lost access to my e-mail and Flickr accounts, but WiFi reception was spotty in most locations anyway.

Glacous-winged Gulls were common along the river:

There were many Bonaparte’s Gulls. Like the terns, they were usually on the wing and moving rapidly in the poor light:

One Bonaparte’s Gull rested briefly as I watched the children fish along the bank:

White-crowned Sparrows were the most common land birds encountered everywhere we stopped during our Alaska visit:

A Red-breasted Merganser swam right up beside the boardwalk, but in the poor light I failed to capture the true beauty of its plumage:

After one night in Soldotna, we broke camp at midday, and started out for Homer, only about 75 miles to the south.

Some important family business caused us to fly up to Illinois in early March, a month earlier than usual. It has been our practice to delay our return to coincide with the onset of spring migration (and our granddaughters’ dance recital!). Although temperatures dropped below freezing almost every night, we were surprised that most days were sunny and mild.

Although the landscape appeared brown and barren, there were certain signs of the change of seasons. During the weeks prior to the arrival of spring, ducks were suddenly present in most bodies of water near our second home.

A pair of Common Goldeneyes race down Fox River at Lippold Park in Kane County, Illinois:

A lone female shows off her “golden eye:”

In a small pond near our condo, the sun behind this Canvasback accents its unique profile:

A pair of Lesser Scaup swims nearby…

…along with a Hooded Merganser:

As they have done for the past eight years, American White Pelicans, on their northward journey, stopped off at Nelson Lake. The plates or “horns” that protrude from their bills signify the approach of the breeding season:

The woodlands along the lake harbor several White-breasted Nuthatches. Here, one assumes its typical pose:

A male Northern Cardinal had been engaged in a lovely duet with his mate, until we interrupted his singing. Here he eyes us suspiciously:

Unlike most perching birds, female cardinals sing a descant while the male leads. This one shows considerable wear on her tail feathers, which will be retained until after the nesting season:

A Song Sparrow provided us with an unusually good view:

In the prairie west of the lake, an Eastern Meadowlark gives us a “salute:”

On the first day of spring, snow blankets the abandoned construction site in front of our condo in North Aurora, IL. Only days earlier, I watched as a female Horned Lark completed construction of its nest, about 50 feet out from our doorstep:

Using our car as a blind, we watched the male Horned Lark sing from the ground near the nest site:

Continuing to sing, he then flew up on a post right in front of us. We were surprised at how “fat” he looked:

This Red-tailed Hawk, with an unusually light breast, has an active nest nearby:

Posted by: Ken @ 12:23 pm

Update on the Rosy-Finches of Sandia Crest, New Mexico. The flag has stopped waving. Although individuals or a few finches have been seen since April 4th, there have been no appreciable flocks. One Black Rosy-Finch was coming in for seed on April 8. Feeders and sighting logs were removed April 9th. Report any late sightings directly by e-mail to Ken.

Update on the Rosy-Finches of Sandia Crest, New Mexico. The flag has stopped waving. Although individuals or a few finches have been seen since April 4th, there have been no appreciable flocks. One Black Rosy-Finch was coming in for seed on April 8. Feeders and sighting logs were removed April 9th. Report any late sightings directly by e-mail to Ken.

Rosy-Finch Epilogue

A final note today from Fran Lusso and Dave Weaver, Coordinators of the Central NM Audubon-US Forest Service Rosy Finch Project at Sandia Crest House, who have contributed so much to the success of the program:Hi Ken,

Well, we are just back from the Crest and have taken down the feeders and the log. It was damp and cold but most of the snow has melting significantly since last week. Colorado is expecting 10-20″ of snow but we might be getting some rain.

Tony, at the Crest House, saw one lonely GC yesterday but the sightings have been just one or 2 since Saturday. The last recorded sighting of a flock was on Friday 4/4/08.

We’ve left a note by the window asking anyone who does sight any rosy finch to email the sighting directly to rosyfinch@rosyfinch.com.

So that’s the season for 2007-2008!

We will resume going up to the Crest to staff the Visitor Center each Wednesday about Memorial Day.

Happy birding!

Fran & Dave

All good things must come to an end, but happily, the seasons do cycle and the rosy-finches will be back in only 6 1/2 months. Allowing time for migration, they spend about as much time at Sandia Crest as on their breeding grounds. This has been a most impressive rosy-finch season at Sandia Crest. It has been a wonderful year for the skiers, and the snowcap promises more than adequate recharging of the Sandia aquifier.

The springs will run fresh and quick in the small canyon where the Northern Goshawk will soon be nesting, and water will overflow at the Capulin Spring “Bird Log.” It has not been a great year for Cassin’s Finches, Red Crossbills, Pine Grosbeaks or Clark’s Nutcrackers, but they invade so unpredictably that this should not get us down. There is always “next year.” Surprisingly, this winter I received NO reports of Northern Pygmy-Owl sightings along the Crest Road, despite their predictable presence at Capulin Spiring and the Sandia Peak ski lift base in past years.

As surely as the excitement of the Crest House extravaganza diminishes, birding in the East Mountains will start warming up. The Violet-green Swallows and White-throated Swifts should now be cruising the mountain heights, and Scott’s Oriole is already looking for a nesting site in Tres Pistolas. The American Three-toed Woodpeckers are daring us to find them as they peel away the bark just to the south of Sandia Crest House. The hummingbird feeders will be out (daytime only, to the consternation of the Black Bears) on the deck.

The nice thing for birders about the Sandias is that there is never a “down time.” While not as spectacular as Southeastern Arizona, our birding is nonetheless exciting.There are enough varied habitats in the Albuquerque area to keep a birder busy for at least a week just to visit them all, in any season.

Migration Update

Spring Warblers are being reported in good numbers in South Florida, the Keys and on the Dry Tortugas. You folks up north, get ready! We plan to join you by the end of the month, and bird Nelson Lake (formally, Dick Young Forest Preserve, in Kane County) our very accessible Illinois “patch.” The White Pelicans will probably have departed, as have the numerous Redpolls, Northern Shrikes and Snow Buntings. Some winter we just must brave the cold and tick off a few birds that, so far, we have only seen in Manitoba.Kane County (IL) “Scope Day,” last November, at Dick Young Forest Preserve/Nelson Lake Marsh, our last visit there before winter set in.

Yesterday the first Least Tern appeared on our small lake. Soon they will be courting on their special “lek,” which happily, is our next door neighbor’s roof! Maybe I will be able to photograph their courtship ritual. The male will catch a small minnow while the female sits watching from the roof. He will bring it to her and impress her with his prowess. Eventually, she will submit, and he will feed her as if she were a helpless nestling.

Our Red-breasted Mergansers (entire series of posts with photos and observations here) abandoned us last week, so we were happy to see the terns today. Let’s admit it– we are bird watchers. We enjoy their activities, interactions and the rhythm of their life cycles. Yes, we will go out of our way to see a rarity, and rejoice when we succeed, but we recognize our limitations (and the price of gas, not to mention our dislike for traffic and gridlock) and extract every bit of enjoyment possible out of the common and (to some) the mundane inhabitants of the bird world.

Northeasterly winds and heavy rains the past couple of days have kept down the migratory exodus from Cuba, but yesterday, “against the winds,” BADBIRDZ caught radar images of flocks squeaking up the western coast of South Florida the previous night, just ahead of some imposing storms that were attacking from the southwest. The good thing about these conditions is that they may cause northbound birds to pile up and then burst forth across the Florida Straits, and soon enough, into the woods and fields and backyards of everyone along the major eastern flyways. So, keep tuned to BADBIRDZ to see if migration picks up.

This morning, just after 7:00 AM EDT, the Miami radar showed another “donut” of (presumably wading) birds expanding/radiating outward from the same area of the Everglades as I noted previously. This time I was unable to save the image and do not know how to retrieve it from the National Weather Service archives. The archives at UCAR did produce a corresponding loop, but the display was cluttered and the “donut” was barely visible. (Note: the UCAR link becomes inactive after about 6 days).

May through October, TUESDAY MORNING GUIDED BIRD WALKS in the Sandia U.S. Forest Service and Central New Mexico Birders meet at 8:00 a.m. (8:30 in May and October) at the |