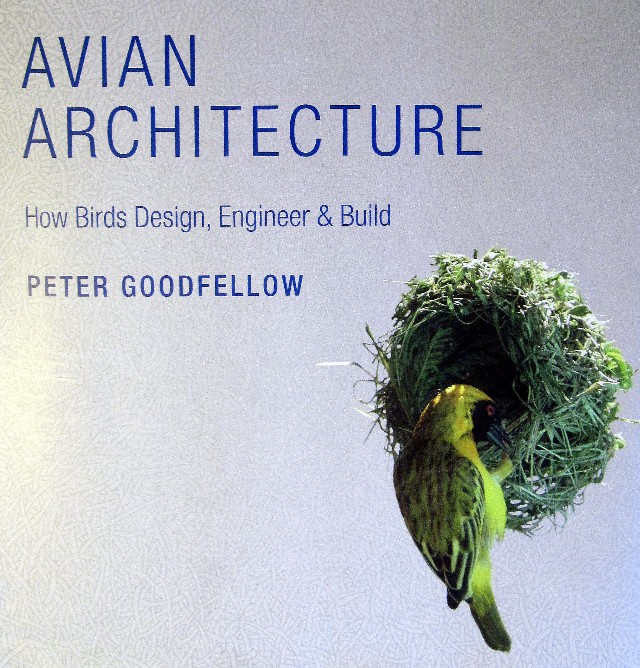

Avian Architecture: How Birds Design, Engineer, and Build

by Peter Goodfellow

Princeton University Press, 2011

What started my fascination with birds? When I delve deeply into the recesses of my memory, I find no sudden epiphany. I recall looking out the back window of our second story apartment on to the flat roof of the dry cleaner’s store, where a nighthawk was sitting on its eggs. My father had discovered it and pointed it out to me. It was interesting to see that the eggs were laid directly on the roof pebbles, without any semblance of a nest. A few days later, the eggs suddenly disappeared. In their place, unbelievably well-camouflaged, were two chicks. Knowing the date we moved away, I was no older than four years. It sticks in my memory, but did it light a flame?

Perhaps a year or so later, when visiting my uncle in a seminary in Ossining, New York, I came across a compact little nest, low in a hedge. Its lining consisted almost entirely of horsehair, and contained tiny spotted white eggs– three, I think. Two small brown birds scolded anxiously as I peered down into the nest. On a subsequent visit I found the nest to be empty, but in perfect shape. I carefully removed it from its attachments to the twigs and put it up behind the rear seat of the family’s 1937 Ford sedan, oblivious to the prohibitions of the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918. It was a work of art and a treasured possession. Over time, much of the straw fell away, but a perfectly pressed cup of horsehair remained.

Later, I learned that the tiny brown birds that wove the beautiful little horsehair nest were Chipping Sparrows. The criminal nature of my act was exposed when I displayed the nest at a Cub Scout meeting. In the meantime there had been other discoveries– Barn Swallows and robins gathering mud in puddles along the road, a Blue Jay whose entire nesting cycle unfolded in a tree only a few feet from an upstairs window…

…the unforgettable fire in the piercing yellow eyes of a Brown Thrasher whose nestlings I dared approach (Kane County, Illinois, May 28, 2010):

Nest structure ranges from the simple to the sublime–

American Oystercatcher nest (Brigantine, New Jersey, May 11, 2007):

Killdeer nest (Batavia, Illinois, May 12, 2009):

Bald Eagles on nest (Pembroke Pines, Florida, October 5, 2011):

Baltimore Oriole male inspecting his mate’s weaving of the foundation for their nest– or is he doing it himself? (May 9, 2011, Kane County Illinois):

As interesting and varied as bird nests may be, they only provide hints about their creators. A Mourning Dove nest can be so flimsy that the eggs may be visible from underneath. Yet, I once watched as a male Mourning Dove collected short lengths of twigs and brought them up to the female who was constructing her nest in a Cottonwood. She inspected each offering, turning the stick in her bill. Almost half the time, she discarded the gift and it fell to the ground. Her critical eye should have resulted in a durable masterpiece of avian architecture, yet a week later, after a rain storm, the nest was gone.

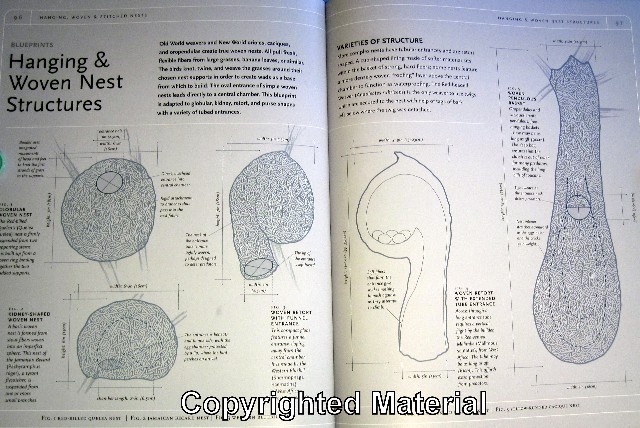

Goodfellow’s Avian Architecture is not only about structural diagrams and blueprints, though it goes into great detail in chapters about nine general types of nest construction, from simple scrapes, holes, platforms, cups, mounds and domes to intricately hanging and woven ones. There are also chapters on aquatic and mud nests, colonial and group nests, as well as intriguing descriptions of courts and bowers, and even edible nests and food stores.

Here is Goodfellow’s set of “blueprints” that introduce the chapter on woven nests, illustrating a variety of styles:

Each chapter discusses construction materials, but most of the book is devoted to case studies of individual species. The representative case studies address where and how the birds construct their nests and the unique features of each. Behavioral traits, breeding biology, habitat and conservation issues are detailed. Global in scope, the book provided me with much new and interesting information about unfamiliar birds.

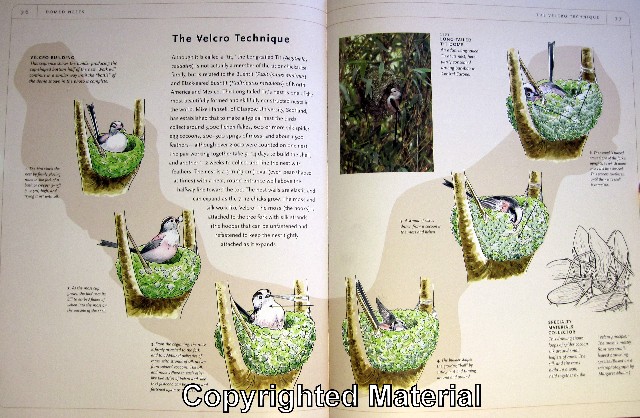

I did not know that birds actually invented “Velcro.” The same system of hooks and loops is used by several species to attach their nests or hold them together. The Long-tailed Tit builds its domed nest by creating loops of silk unwound from spider cocoons and fastening them to sprigs of moss. The selected moss leaves are just the right size to interlock with the silken loops. The attachments can be disengaged and repositioned to accommodate the growth of nestlings.

In each chapter, for a representative species, the author provides a very detailed and illustrated example of the steps involved in construction of the particular nest type, from beginning to end. Whether the bird is unfamiliar or one that is commonly encountered, these contain many interesting facts.

In the chapter on domed nests, the Long-tailed Tit’s construction methods are presented sequentially:

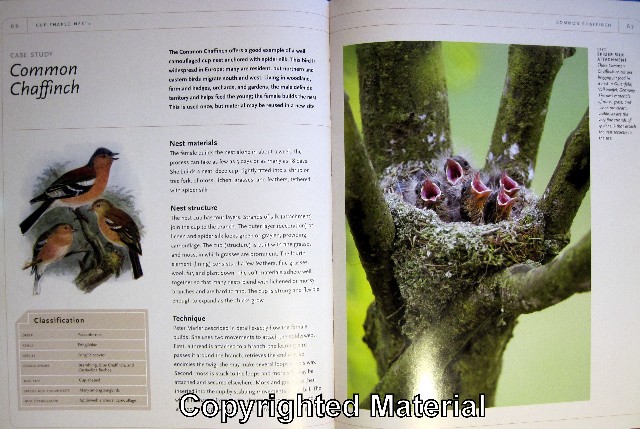

The Sooty-capped Hermit and the Common Chaffinch also use a similar technique. Two page case studies of selected species reveal many other interesting facts:

I learned that one of the largest nests of any bird species is that of the Social Weaver– a “condominium” that begins with a platform roof and includes up to a hundred separate compartments, individually built and occupied all year long. All residents share responsibility for maintaining the roof.

Nests are generally constructed from locally available materials, so they reflect adaptation to a wide range of habitats. The flamingo creates a trough around the perimeter of its nest site as it removes mud for its construction, while the Black Wheatear must utilize stones gathered from the high and treeless rocky slopes of the Atlas Mountains of Spain. It carries the stones, one at a time, to its nest site. Amazingly, we learn that this 1 1/3 ounce bird is somehow capable of moving rocks weighing as much as 10 ounces. Another example of the use of rocks in nest construction is that of the Horned Coot, which creates its own artificial island by piling stones into a cone up to 13 feet wide and three feet high.

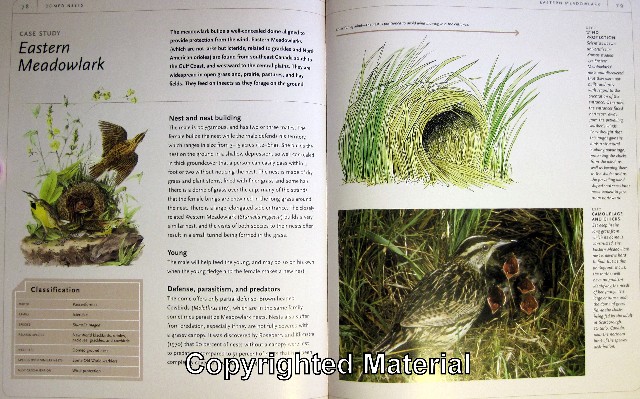

The Eastern Meadowlark weaves fresh grass stems into the structure of the domed roof of its nest:

:

I have seen Northern Goshawks and Bald Eagles bring fresh green leaves to the nest. Other birds commonly incorporate greenery into nest construction. Whether it serves a function such as camouflage or pest deterrence, or is merely decorative is the object of speculation. I was a bit disappointed that the book’s index did not have an entry for green leaves or foliage, nor one on camouflage despite providing several pertinent examples in the text. Neither are there entries for vermin or mites, though the subject comes up a number of times.

The relatively brief index addresses mainly common and scientific species names. While this is a minor drawback, it somewhat limits the reader’s ability to search the text for some common elements in techniques and construction. . For example, when I wanted to find all references to the use of spider web or silk I found only three citations. One discusses the strength of this material in the section on hummingbirds’ nests, and the other two refer to its use by the Common Chaffinch. Yet, the book has other very pertinent descriptions of how birds use spider silk. For example, the Common Tailorbird utilizes spider and lepidopterus silk, as well as plant down, in attaching its rainproof nest under an arching leaf.

Also not indexed is a particularly intriguing method by which the Sooty-capped Hermit hangs its nest from a single “cable,” comprised of many strands of spider silk, which is attached to the edge of an overhead leaf. Since the nest could swing precariously and even tip over, this hummingbird adds a “tail” of spider silk cable beneath the nest and weighs it down with pellets of mud. The weighted tail serves as a counterbalance that keeps the nest from spilling out its contents.

Construction materials such a mud and silk are sometimes cross-referenced, but moss, hair, feathers, rocks or stones are not. However, the case studies provide interesting examples of specialized use of these components.

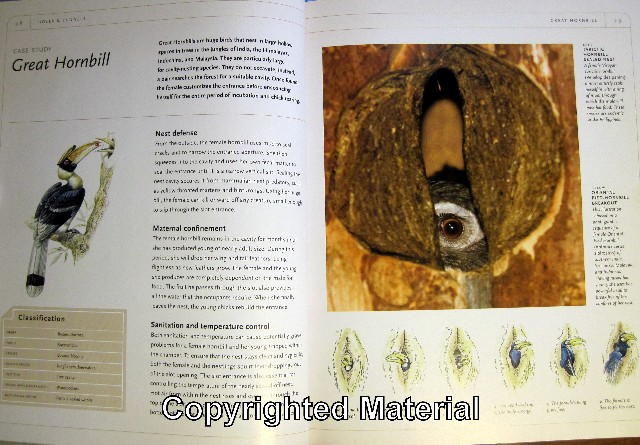

The female Tarictic Hornbill uses mud to seal herself into a brooding chamber for many months to lay eggs and rear young until they are completely fledged, depending upon the male to feed her and their offspring:

The final two chapters of Avian Architecture go beyond descriptions of the nest as a structure in which eggs are laid and young are reared. There are extensive and detailed case studies of courts and bowers, and the final chapter treats edible nests and food storage methods.

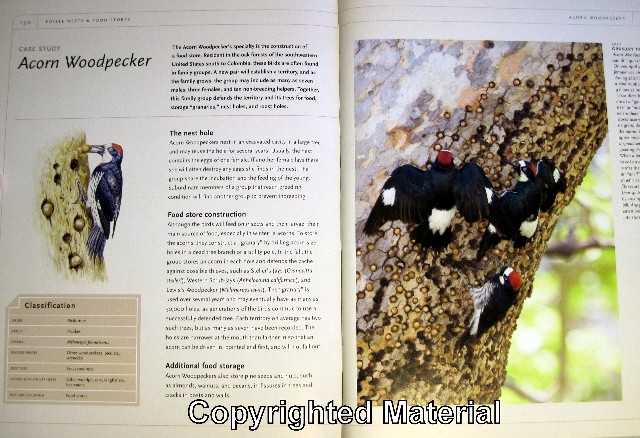

Studies of the Yellow-bellied Sapsucker’s technique for extracting sap and assuring its free flow, and the Acorn Woodpecker’s method of storing acorns and are especially interesting:

.

Avian Architecture is an entertaining and informative resource for anyone interested in the great diversity of bird nests, and the what, why and how of their construction.

Posted by: Ken @ 6:25 pm

Since moving to South Florida in 2004, we have taken a rather perverse pride in never needing to turn on our central heating system. Some cool winter nights we might bundle up and throw one of our down comforters on the bed, but it never got so cold long enough to justify turning up the thermostat. We actually did not know whether our heating system even worked!

For nearly two weeks in early January, all of the southern US experienced a prolonged spell of historically low temperatures, For three nights in a row our overnight temperatures dipped very close to freezing. Exotic tropical lizards such as Iguanas fell into stupor and rained down from the trees. We were treated to news stories such as this: Florida cold spell knocks iguanas from trees, and a viral You Tube Video: Frozen Iguanas Fall From Trees.

The cold also took a heavy toll on tropical fish. Commercial fish hatcheries that catered to the pet trade suffered huge losses. Introduced species, particularly tilapia and other cichlids floated to the top of canals and lakes. The ditch along the trail in our local birding patch was littered with the corpses of such species. I realized that this was likely the reason why there were so many herons, storks and ibises along the ditch last week, when I walked the “patch,” and saw an abundance of waders. I also encountered a Cottonmouth Moccasin and two Bobcats. This week I went out again, especially looking for Bobcat tracks.

This Pond Cypress was decorated with nicely spaced white waders:

Wood Storks had exclusive use of my favorite old snag:

Walking along the ditch, I flushed out several more storks:

A small flock of White Ibises flew overhead:

Small birds were scarce. I got a fleeting glimpse of a Swamp Sparrow in its usual thicket, but this Gray Catbird posed for me, showing off its rusty undertail coverts:

A Common Yellowthroat perched on cattails next to the ditch:

An abundance of butterflies made up for the lack of birds. This White Peacock was a small specimen, with only about a 1 1/4 inch wingspan:

This Zebra Heliconian was likewise very small. I wonder why:

An appropriately diminutive Firey Skipper probes a flower with a tongue that is as long as its body:

It had rained quite hard, but briefly, the day before. I knew that it would be a perfect morning for tracking, as the rain would have obliterated the old footprints and bicycle tracks. Sure enough, there were several places in the trails where puddles had formed and partially dried up. This provided a nice clean background. The tracks were mostly from raccoons and deer, but I did find the Bobcat tracks.

Having read up on signs of Bobcats, I learned that, unlike tabby cats, Bobcats do not bury their feces, except those near a den with cubs. Instead, they deposit them conspicuously on rocks or on piles of stones they assemble. This serves to advertise their territory. I found several old piles of scat. Earlier, believing that they might be from Coyotes, I had photographed some of these when still fresh. I’ll spare you a photo, but if you are curious, look here.

There have been no reports of local Coyote sightings, and the placement of piles of feces, mostly on flat rocks in the middle of the trail in Bobcat territory makes me believe they came from the latter species.

Here is an older scat pile that I photographed this week:

Ironically, while I was engaged in scatological studies on the ground, I frightened an Anhinga that had been fishing in the ditch next to the trail. It uttered an irritated squawk, flew low and away, but doubled back, heading right towards me. Expecting a perfect flight shot, I raised my camera and got the bird in the camera’s viewfinder. Just as I was depressing the shutter, the Anhinga let loose with a barrage that was headed right at me! I jumped to my right, and the excrement barely missed my left shoulder. I cannot help but think it was an act of retaliation.

Turning to another unpleasant subject, I again saw several Cottonmouth Moccasins. One, swimming in the ditch, particularly intrigued me. As I watched, the snake encountered a dead fish. It appeared to “smell” it by resting its chin on it and thrusting out its tongue.

Then, to my amazement, the moccasin took the fish into its jaws, shook it as if to break off a piece, then disappeared briefly under the water with it (click on photo for sequential series of pictures):

When it surfaced, the snake’s mouth was empty. In fact, it opened up its mouth for a moment. There did not seem to have been enough time for it to swallow a portion:

Then, the snake moved away, now apparently ignoring the dead fish:

Truly, I thought I had witnessed something new to science! Cottonmouths, with their long fangs and poison glands are so well adapted for killing and eating live prey. Why would one display such an interest in the partially decomposed carcass of a fish? As I subsequently learned, the Cottonmouth’s scavenging habits are well known to science. Indeed, some populations of this species subsist almost entirely upon fish that are dropped by colonial nesting birds such as herons.

References:

South American Journal of Herpetology

The success of this species [Cottonmouth Water Moccasin] on islands is attributable, in part, to a broad trophic niche that encompasses many prey items including carrion. Numerous cottonmouths living on the island of Seahorse Key consume primarily dead fish that are dropped from colonial nesting bird rookeries, but they also prey on rats (Rattus rattus) that are invasive fauna on the island. While alternative prey items (e.g. lizards) are available to newborn snakes, smaller individuals also scavenge for fish carrion at early ages.

Pitviper Scavenging at the Intertidal Zone: An Evolutionary Scenario for Invasion of the Sea.

It is difficult for terrestrial vertebrates to invade the sea, and little is known about the transitional evolutionary processes that produce secondarily marine animals. The utilization of marine resources in the intertidal zone is likely to be an important first step for invasion. An example of this step is marine scavenging by the Florida cottonmouth snakes (Agkistrodon piscivorus conanti) that inhabit Gulf Coast islands. These snakes principally consume dead fish that are dropped from colonial nesting bird rookeries, but they also scavenge beaches for intertidal carrion, consuming dead fish and marine plants, and occasionally enter seawater.

Scavenging by Snakes: An Examination of the Literature

Although it is widely known that most species of snakes readily accept carrion in captivity, the notion of scavenging by wild snakes historically has been rejected or ignored. Herein, we review the literature describing instances of scavenging by snakes and consider the implications of carrion use on their ecology. Thirty-nine published accounts yielded 50 observations of scavenging by snakes (43 from field observations and seven from laboratory studies). Thirty-five species from five families were represented, but pitvipers and piscivorous snakes were represented more frequently than other groups.

Posted on Mon, Feb. 08, 2010

Cold took heavy toll on Florida wildlife

BY CURTIS MORGAN

cmorgan@MiamiHerald.com

Despite four decades of slogging through Everglades marshes and mangroves, wildlife ecologist Frank Mazzotti had never experienced anything like the aftermath of frigid January. The confirmed casualty count so far:

· At least 70 dead crocodiles.

· More than 60 manatee carcasses.

· A bright-side observance of multiple frozen-stiff Burmese pythons, the scourge of the Everglades.

And also, perhaps the biggest fish kill in modern Florida history.

“What we witnessed was a major ecological disturbance event equal to a fire or a hurricane,'’ said Mazzotti, a University of Florida associate professor. “A lot of things have happened that nobody has seen before in Florida.'’

The cold was simply brutal on many tropical plants and animals. Toxic iguana-sicles dropping into the mouths of unfortunate pooches was only the tip of the iceberg that descended for two weeks on South Florida.

While scientists are still surveying losses, it’s already clear that the record chill wiped out shallow corals in the Keys and devastated manatees. A preliminary assessment that Everglades National Park scientists completed last week also documented a broad and heavy toll on everything from crocodiles to cocoplums to butterflies.

Dave Hallac, the park’s chief of biological resources, summed up the impact in a word: “substantial.'’

Cold spells, like hurricanes and fires, are part of the natural cycle in South Florida, and scientists believe the system will recover — but some species will certainly rebound more slowly than others.

“I wouldn’t expect any catastrophic long-term kind of effects,'’ said Luiz Barbieri, chief of marine fisheries research for the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. “Most likely, this has happened occasionally over thousands of years. The system has adapted to these episodic mortality events.'’

Still, mortality numbers like this haven’t been seen in decades in the park.

A record number of endangered manatees died from cold stress, most of them — more than 60 — found in park waters stretching into the Ten Thousand Islands on the Southwest Coast. More than 70 carcasses of North American crocodile were counted, a significant hit to a species removed from the endangered list only three years ago.

About 40 species of pineland plants suffered varying degrees of frost damage. On some tree island, cocoplums looked like they were burned. Half of the population of a caterpillar that morphs into the exceedingly rare Florida leafwing butterfly died.

Then there were the literally countless dead fish — from tiny pilchards to large snook and tarpon.

The report — compiled by Hallac and colleagues Jeff Kline, Jimi Sadle, Sonny Bass, Tracy Ziegler and Skip Snow and based on aerial and water surveys and reports from a host of other observers — underplayed actual losses. It’s impossible to cover an area as vast as the park, and carcasses can sink, float into thick mangroves and easily go overlooked.

TAKING ACTION

While the park has experienced colder days, January’s chill was long and intense, punctuated with overcast skies, rain and one sub-freezing plunge. Mazzotti called it a “perfect storm'’ that left literally no warm refuges.

The chill was particularly dramatic in coastal waters. The park recorded temperatures that hovered below 68 degrees, a cold-stress limit for manatees, for 18 days; and below 60, the stress limit for snook, for 14 days.

“I’m really worried about the snook down here,'’ said Hallac. “It was amazing to see how many of the large, more mature, spawning-age fish were killed.'’

The FWC has already closed snook season until Sept. 1. After reviewing catch reports and samples taken by scientists in coming months, the agency will decide whether to extend the ban on keeping the popular fish or changing regulations to protect any others, Barbieri said.

Cold-blooded reptiles and tropical plants and fish fared the worst, but some Glades species weathered the nasty weather well. Birds, for instance, emerged largely unruffled, and some were observed scavenging fish.

Only one death of an alligator, which reside happily in Louisiana, was reported. Crocs, at the northern end of their range in South Florida, died by the dozens, including one familiar to many anglers who fish Flamingo. The 13-foot, 450-pound croc, tagged as a hatchling in 1986, frequently lurked near the Whitewater Bay boat ramp.

The cold did benefit the park’s battle to control exotic invaders. Frost slammed Old World Climbing Fern, an aggressive vine that smothers natives. Other exotics, from Asian swamp eels to the infamous Burmese python, also took hits scientists intend to further study.

THE STRUGGLE AHEAD

Scientists said recovery rates will vary among species. While snook, popular with sports anglers, has gotten the most attention from the public, the cold may have been more crippling to Goliath grouper, Barbieri said.

The fish, which can grow to massive size, nearly disappeared from Florida but had rebounded so well in recent years that wildlife managers had begun considering lifting a ban on keeping them. Goliaths died in massive numbers in the shallow Glades, considered a prime nursery. They also grow far more slowly than snook, taking six years or more to reach maturity, Barbieri said.

For some hard-hit areas and species, other outside factors can hinder recovery. Everglades marshes and coral reefs aren’t nearly as healthy as they were hundreds of years ago.

Invasive plants, such as Brazilian pepper, weren’t around to crowd out battered natives.

“If you’re totally healthy and get a cold or flu, it’s not a problem. If you’ve got diabetes and heart problems, it could be a lot more serious,'’ Hallac said. “The park is in that kind of compromised condition.'’

On January 26, I accompanied a group of 7th grade science students on a field trip to Flamingo Gardens, a private arboretum, preserve and wildlife rehabilitation facility in Davie, Florida. These students are studying the effects of traffic on the behaviour of the Bald Eagles nesting only about 200 feet from a busy boulevard. They designed forms, upon which they record traffic density and check off the various actions of the birds, whether one or both of the adults are present at the nest, their vocalizations, and any indications of nervousness or avoidance.

Greater Flamingos and White Ibises make a pretty picture, even with my old 2 megapixel point-and-shoot:

A curator exhibited a Great Horned Owl with a broken wing that was beyond repair:

Other obligations (including much correspondence with Florida officials about our concerns for the safety of the nest because of the planned construction) have kept me from going afield for the past few days, but I hope to get out to see our neighborhood Bald Eagle nest tomorrow. For an update on the status of the planned construction, visit this link. I last visited the nest on Tuesday, January 27th, when the first chick was 11 days old.

The female was sitting quite high in the nest. Perhaps this is an indication that a second chick has hatched and the eagle does not have a third egg to incubate:

While watching the nest I saw movement through the sticks that make up the nest cup. Several times. a spot of white appeared and then disappeared, just a few inches away from the adult bird, which often looked down into the nest. I assumed the spot of white was the down of an eaglet’s head.

Here is a photo showing what I believed to be the rounded head of a chick, with the left half partly in shade (click on the photo and select the full sized view):

Moments later, the white spot disappeared, and I assumed the chick had crouched down:

Now I am not sure, as I may have things reversed. It is possible that the white area is a view of the sky, along with the right margin of the tree trunk, and actually the second photo shows the area obscured by the chick. In any event, the chick was moving about, and we are anxious to see it reaching up to be fed.

Staying at home did not deprive me of a few backyard photo opportunities. A Palm Warbler foraged on our patio, and I photographed it through the window glass:

This Cooper’s Hawk flew right over my head, but I still have troubles focusing on moving targets, and my full-screen image was just a blur. Here are a couple from farther out, when I had time to focus (click on photo to see the other image):

A Great Blue Heron was cooperative as it fished in thigh-deep water just off our back lawn:

Sunrise from our patio:

Book Review- Birdwatcher

BIRDWATCHER

BIRDWATCHER The Life of Roger Tory Peterson

by Elizabeth J. Rosenthal

The Lyons Press, Guilford, Connecticut

Based upon interviews with hundreds of Roger Tory Peterson’s family, friends and associates, and supported by pertinent excerpts of his and others’ writings, Elizabeth J. Rosenthal chose an interesting approach to his biography. The result is a balanced and highly readable history of Roger’s central role in building the hobby, sport and science of birding into an essential part of the environmental movement.

Parallel narratives with various themes overlap deliberately, avoiding the problems with a chronological approach which may cause the reader to repeatedly refer back to earlier periods in the life of the subject, in an attempt to piece together people and events. While Peterson’s birth, on August 28, 1908 is recorded on the third page, and his death, in 1996, on penultimate page 389, this is not a serial recitation of events. Rather, in nineteen chapters, the author takes us through six selected aspects of his path to fame, revealing not only his great strengths and achievements, but also his weaknesses and failures.

A truant paperboy from Jamestown, NY, twelve year old Roger had an “epiphany,” when an apparently lifeless flicker burst into flight at his touch: “Ever since then, birds have seemed to me the most vivid expression of life.” Ernest Thompson Seton’s Little Savages book inspired the boy Roger to develop a system to identify ducks, and eventually other birds, by their “uniforms,” or distinctive plumage characteristics. As a young naturalist at the new Chewonki, Maine Audubon Camp, he introduced this concept to his students. It was to become famous as the “Peterson System” of bird recognition.

In 1936 he married Mildred Washington, who was a camper at Chewonki, but their relationship was strained and lasted only about five years. We follow his early career as educator and bird artist, and in 1937, as author of the groundbreaking A Field Guide to the Birds, through its second revision, in 1939. In 1942 and employed by the National Audubon Society, Peterson viewed the last Ivory-billed Woodpeckers in Louisiana’s Singer Tract.

He was drafted into the US Army and married Barbara Coulter, who was to become the most important figure in Roger’s life. Barbara learned her birds from the “old Chester Reed guide” that was always on the windowsill of her family’s breakfast room. In the Army, Roger conducted a flawed study of DDT which concluded that it is not harmful to birds. Eventually, he joined the science-based campaign to ban the pesticide. He supported Rachel Carson during her long and contentious war with the chemical companies and land grant universities who fought the DDT ban. There followed an extremely productive period of writing, most notably his authorship of Birds Over America, that showcased the beauty of birds as well as his prose. He authored or collaborated on the acclaimed series of Peterson Field Guides, and traveled the world as the most recognizable naturalist of his time.

In the meantime, as Roger expanded his horizons, Barbara Peterson evolved into his general manager. When he co-authored the immensely popular Field Guide to the Birds of Britain and Europe, a British ornithologist named James Fisher was editor. They developed a 20 year friendship, embarking in 1953 on the famous hundred day trip around North America from Newfoundland to Alaska via Mexico, to be chronicled in their book Wild America. James’s death at a young age devastated Roger.

Often overlooked by casual birders, Peterson’s contributions to the cause of bird and habitat conservation are extensively covered in this biography. Besides his work in North America on the decline of the Osprey, Peregrine Falcon and Bald Eagle due to DDT, he was an imposing force for species preservation at home and abroad. From his bully pulpit, he educated the public and lawmakers about endangered species and the causes of their decline, and effectively lobbied for funding of conservation programs. In Spain, he fought to spare the huge Coto Doñana from agricultural and commercial development. Although the struggle continues to this day, Peterson had a central role in obtaining public support and funds for the Coto’s preservation. Likewise for Lake Nakuro in Kenya, especially famous for its millions of flamingos, and Midway Atoll, where Peterson helped thwart a plan to exterminate its entire population of Laysan Albatrosses. And so on: Patagonia and Tierra del Fuego, Argentina, the Galapagos Islands, and the Antartic—in each case Roger was instrumental in changing the tide against development and exploitation.

We gain insights into Roger Tory Peterson’s personal traits— his enormous intellect and excellent memory, his shyness, detachment from family life, his absentmindedness and dependence on others to meet many of his personal needs. Yet, he was dissatisfied with his painting career, wishing to devote more time and effort into “painterly” works rather than “illustrations.” In his later years he appeared to be competitive with and jealous of the younger field guide authors, and was severely stung when the new crop of birders insensitively criticized and even ridiculed the fourth (1980) revision of his Field Guide.

After years of emotional estrangement, his marriage to Barbara ended amicably in a 1977 divorce, probably because Virginia Westervelt, who subsequently married him, supplied some of the nurturing and adulation which he craved. Virginia exercised great control over Roger’s schedule, deciding who could make appointments with him, and when, to the great distress of his family.

Roger was “shortsighted,” and some said he was obsessed and wanted to talk and think only about birds. Yet, this greatest weakness was also the source of his strength— an ability to focus on his subject. And the truth is that Peterson was an extremely well-rounded naturalist, having a great interest in the entire natural world: flowers and insects, and especially ecology. The book details the several times when he neglected his own health and safety in pursuit of birds, the most famous incident being his near-drowning and rescue by the Coast Guard off the coast of Maine.

Roger Tory Peterson’s most enduring legacy was the inspiration he provided to a whole new generation of birders. Rosenthal devotes an entire chapter to thumbnail sketches of Peterson’s “Worldwide Progeny,” who owe so much to their mentor. All are names familiar to serious birders. The book includes fourteen pages of photographs of Roger and his friends and associates through the years, and a list of all the people interviewed by Rosenthal. There are also extensive chapter notes and suggestions for further reading. A very useful feature is the fourteen page index that permits quick cross-reference to people and events.

So many times, as I read Elizabeth Rosenthal’s biography, my mind wandered back to my own experiences over the decades. I grew up with Roger Tory Peterson. He was my friend and constant companion. I first met him when we both were emerging from the depths of the Great Depression. He, a twenty-something naturalist and painter, and I, a six-year-old who, as a toddler, watched pigeons and starlings from the back window of an apartment over a meat market in New Jersey.

It was my mother who introduced me to Roger, unwittingly fanning a spark that was to grow into a flame. Only today, facing the irony of a recession and the specter of another Depression, do I realize what a sacrifice it was for my mother to spend $2.75 for the 1939 revision of the first edition of Peterson’s A Field Guide to the Birds. In today’s economy, that comes to $34.37, plus tax. The book supercharged my interest in birding and opened the door to a lifelong hobby– it might be called an obsession.

The Guide replaced my first “real” bird book, a pocket-sized copy of Land Birds, by Chester A. Reed. It was badly defaced, for I traced the outlines of the book’s small format bird pictures, perhaps to engrave them into memory. As soon as I matched one of them up with a dooryard sparrow, robin or jay, I penciled “SAW” in big block letters over the corresponding image. Alas, my initial Life List was eventually assigned to the trash heap. Not so with my treasured original Peterson Guide. Although now yellowed, soiled and loosely held together, it is witness to the respect I accorded it.

Many more times, and in many places, I consulted Roger and delighted in what he told me about birds, in the pages of the Junior Book of Birds, the Junior Audubon leaflets, and in his Birds Eye View and other columns in Audubon and Bird Watchers Digest. Only twice did he speak to me in person, but both times I was part of a large audience. Once, when I was in my teens, I attended an Audubon Screen Tours presentation which he personally narrated. I cannot remember the topic of his film, nor a single word he said. It must have been in a state of awe at finally seeing the Great Man. Later my son and I flew out from Dallas to New Mexico, where Peterson spoke to a packed house during the Festival of the Cranes. We never got near him, and he birded Bosque del Apache privately with a small group.

Ever faithful, I purchased every subsequent revision of the Eastern and Western as well as the Texas bird guides, as well as many of the Peterson Guide series. In his magazine columns, I followed his adventures and his brushes with death. I especially remember one column in which he complained that, with advancing age, he had developed very poor tolerance to heat. He felt he would be making far fewer trips to Arizona. Rosenthal’s biography relates the beginning of Rogers descent into terminal ill health. In September, 1995, eighty-seven year old Roger spoke at a dedication ceremony in McAllen, Texas, in 91 degree heat. After giving brief remarks in the full sun, he collapsed with heat exhaustion. A stroke followed not long after, and he died in July 28, 1996.

Like Roger, I had a “epiphany” as a kid, when, concealed by shrubbery, I peered into a clearing where a courting Rose-breasted Grosbeak was displaying before a female of its kind. The color and the beauty of its dance have stayed with me. My wife, Mary Lou had a similar experience that started her into birding. Before we took our first birding tour together into Arizona (to which she reluctantly consented), she thought it best to at least look in my Field Guide at the birds that were supposed to be such an attraction. She settled on the Elegant Trogon, as if she could just order one up for the trip! Well, in Garden Canyon, she saw a male and a female trogon, both at close range and in beautiful plumage. That did it.

Looking due east from our patio, we see that the waves are now coming in diagonally from the left. The wind is shifting eastward.

The lake is most interesting when the wind is still, when it is easy to see the bass splash to capture insects on the surface, or groups of small fish jump out of the water in unison, porpoise-like, to escape an underwater predator. The lake reveals quite a bit about the weather: wind shadows, wave intensity and direction. It signals sudden downbursts from thunderstorms and shifting winds.

Watching the lake last evening, after two days of steady northwest winds, we saw the wind shift to the northeast. High pressure is moving down along the east coast of Florida, and with it a gradual shift of wind direction to perhaps southerlies by tomorrow night. The waves on the lake signaled that waves of warblers were unlikely, but I checked the radar before turning in.

Despite the continued fairly strong NE winds, and no movement north from Cuba, Key West radar showed a burst of birds at 8:31 PM, slipping up the west coast of Florida towards Naples and along the west coast of Florida. This morning, BADBIRDZ confirmed that there had been little or no action across the Florida Straits, though there had been movement inland to the north, with, showing migrants exiting the Sunshine State.

A good sized flock is exiting from the SW tip of the Florida Peninsula, north of Flamingo, near Whitewater Bay and Oyster Bay in ENP. They are speeding along across the wind, at about 40 MPH.

Then, a little after 10:00 PM, this loop from Miami radar shows the same flock making progress up the coast, and a large number of birds exiting western Broward County and heading northwest towards Fort Myers.