Posted by: Ken @ 9:36 am

by William J. Boyle, Jr

Kevin T. Karlson, Photographic Editor

Princeton University Press

This attractive book, by the author of A Guide to Bird Finding in New Jersey, is packed with information about the historic and present abundance and distribution of the 465 (including extinct) bird species ever officially recorded in New Jersey. For over 450 species there is an emphasis upon population trends and changes in range over the past ten years. The large number of species is a reflection of the great variety and richness of habitats in this small and densely populated state.

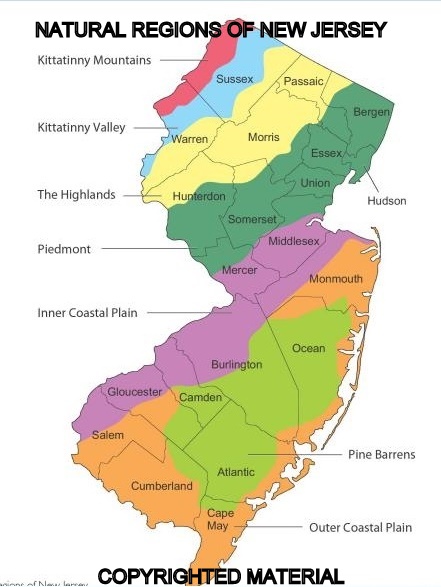

These general natural bio-geographical regions are further refined and subdivided in the narratives:

The Introduction includes a brief description of the geography and natural regions of New Jersey. There is a review of the history of previous systematic records of birdlife in the state, beginning with an 1897 compilation by the Fish and Game Commission, up to the most recent work of the New Jersey Bird Records Committee, and current data from eBird and regional rare bird alerts and birding hotlines. In 1998, the State List included 443 species; an additional 15 new species have been documented since then. Adjustments due to splits, and re-evaluation of a specimen and previous records resulted in an official net increase of seven species.

For each species as appropriate, there are notes about approximate migration and breeding dates, as well as habitat descriptions. In some instances, abundance is related to such factors as tree crops and unusual weather disturbances. Large and legible colored maps detail the seasonal distribution of the more common birds, while rare sightings may be shown as dots, with descriptive details for species seen five or fewer times during the past decade. Species that may be found only in a small or restricted area are given special attention.

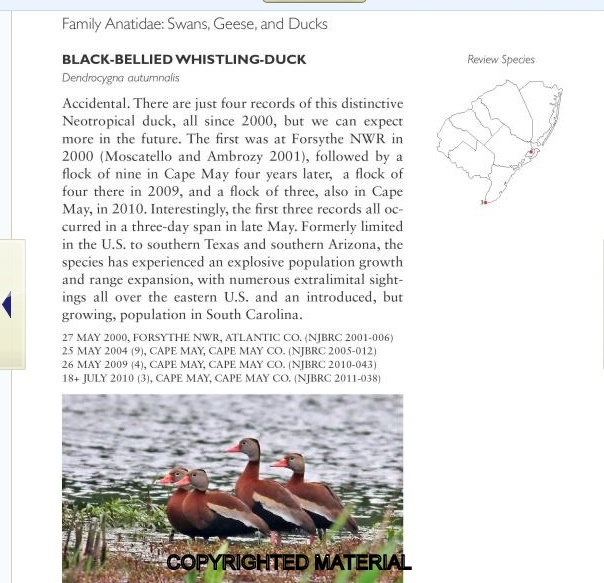

Species accounts are notably up to date, as illustrated here:

There are over 200 color photographs taken within the state, including both common and rare species. Some of the photos are included for their historic rather than aesthetic value, to document occurrence of rarities. Appendices address exotics and species of uncertain provenance, species referred to in earlier lists or publications as having been seen in New Jersey, but presently not accepted the NJ Bird Records Committee, review species (reports of which require additional documentation), and additional identification information for certain photos.

My interest in birds developed during early childhood in New Jersey in the 1940s. Those were the days before completion of the NJ Turnpike and Garden State Parkway, before people asked “which exit?” when they heard someone was from New Jersey. I grew up in Rutherford, located in the northeast part of the state, only six miles from New York City, and became quite familiar with neighborhood bird species. The mostly undeveloped flood plain of the Passaic River was a five minute walk from my home, and a short bicycle ride took me “down the dumps,” as my friends and I then called the most accessible portion of the meadows along the Hackensack River.

I learned to identify birds at a very early age, collecting bird pictures from Arm & Hammer Baking Soda boxes. My first “real” bird guide was a small format book by Chester A. Reed, Land Birds East of the Rockies. There was a picture of a different bird on each page with descriptive text next to it. As I identified each bird in the book, I penciled across its picture in big block letters: “SAW.”

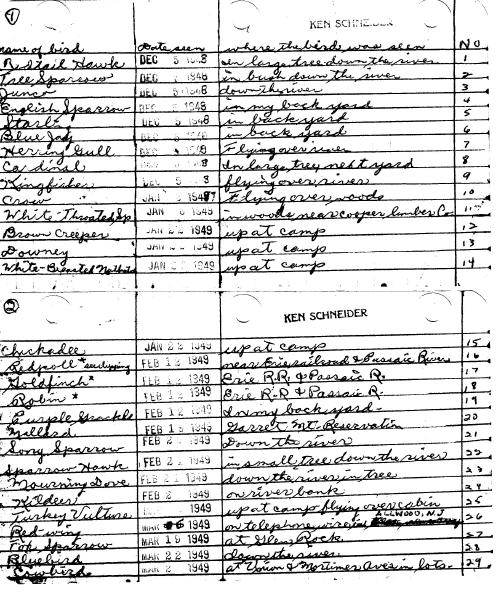

As a Boy Scout, in the winter of 1948, in quest of a merit badge, I suddenly began keeping an orderly list of the birds I saw. With Monkish precision I drew grid lines on 4×7 loose leaf sheets, with headings: “Name of Bird… Date Seen…Where the Bird was Seen… ,” and numbered each entry. I used my date stamp as if it had the power of a wax seal that certified the authenticity of my sightings.

Here are the first two pages of my Life List:

My notes gave special names for many of the sandy hills, wetlands and and woodlands along the Passaic River that harbored the nests of herons, thrashers and cuckoos. They all have since disappeared, swallowed up by housing developments. The Meadowlands Sports Complex now covers one of my favorite “dumps.” Another particularly smelly one, in Lyndhurst, later earned the respectable name of “landfill” and grew into “Mount Trashmore.”

Now my “dump” is known as Kingsland Outlook, part of Richard W. DeKorte Park, famous as a birding hotspot:

I witnessed great changes while confined to my small corner of New Jersey during the ten or eleven years before 1953, when I got my driver’s license and graduated from high school. In later years, my written records addressed mostly rarities and new life sightings.

In the 1940s, pesticides were used copiously to fight Dutch Elm disease, and surely killed American Robins and Wood Thrushes by the hundreds and thousands. Weakened and dying birds appeared on neighborhood lawns and estates. My cousins and I collected some of these “tame” birds in cardboard boxes and fed them water with an eye dropper, thinking that perhaps they were suffering from starvation or heat stroke, but they all died under our care. My father said he thought they may have been poisoned, but I didn’t connect their deaths with the tree spraying program. It was nearly twenty years later that Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring alerted the world to the dangers of pesticide misuse.

In the early 1940s it seemed that every suburban home had Wood Thrushes nesting in their foundation plantings. In springtime, colorful warblers and other neotropical migrants adorned the leafless trees and shrubs. Peregrine Falcons (then called “Duck Hawks”) nested in aeries high on the Palisades along the Hudson River. I looked forward to perusing Boyle’s book with a Rip Van Winkle mind-set, ready to be surprised by the changes in the number and distribution of New Jersey’s birds over more than a half century. I was not disappointed.

Paging through this book, my attention was naturally drawn to those old, familiar species of my childhood. How have they fared? Have some of the less common birds changed in abundance? Have new species invaded my old turf? It was a relief to find that Wood Thrushes remain abundant. Of course, House Finches and Cattle Egrets were unknown to me in the 1940s, and I was aware of how they invaded New Jersey by the 1970s, but from Boyle I learned that numbers of both species have since plummeted. Bacterial conjunctivitis caused a 50% drop in House Finch populations in the late 1990s, though they are still widely distributed in the state. The number of breeding Cattle Egrets peaked in the 1980s, but now the breeding population has nearly disappeared from New Jersey.

At ten or eleven years of age, I received the gift of a used copy of Allan Cruickshank’s 1942 book, Birds Around New York City: Where and When to Find Them. Its coverage area included all of northeast New Jersey, and it became my benchmark reference, and sometimes a source of pride when I found a new bird. It also spurred me to begin keeping records of my observations, which I peppered with citations from Cruickshank’s book.

Common Redpoll, February 12, 1948, Rutherford - “This northern finch… is a decidedly irregular winter visitant, usually very rare…In most counties it is recorded only three out of every five years [Cruickshank page 442].”

Iceland Gull, December 26, 1949, Belleville - “It is …still and uncommon to rare winter visitant in the New York City region, and a recording of the species continues to give local enthusiasts a great feeling of satisfaction [Cruickshank page 223].”

Boyle indicates that both species remain scarce. The redpoll is still rare to uncommon as a winter visitor or migrant. The Iceland Gull’s numbers peaked in the 1970s, and they have become less numerous in recent years.

“Eastern” Evening Grosbeak, October 21, 1951, Garret Mountain - “Seen as early as November 13, 1915… and October 27, 1927 …but… the bird seldom arrives before Christmas…the recording of this species in the New York City region is still a red-letter occasion, and I know many an active observer who is yet to see this species locally. [Cruickshank, page 438].”

Boyle reports that Evening Grosbeaks increased substantially, beginning with an incursion during the winter of 1950, peaked in the 1970s, but “have declined markedly since the mid-1980s.”

“Eastern” Glossy Ibis, April 26, 1952, from the boardwalk at Troy Meadows - “An accidental visitor from the south…(seen) at Troy Meadows, New Jersey …May 26, 1937… (and) May 21, 1939… In recent years there have been marked flights just to the south of us, and there are now many records for southern New Jersey. [Cruickshank, page 79]”

My Glossy Ibis sighting, the first northern New Jersey record in 13 years, was never officially accepted. A few days after seeing it, I duly reported it at a meeting of the Hackensack bird club at Odd Fellows Hall. My companion at Troy Meadows had been an older but less experienced birder, who also saw the unmistakable crow-black long-legged heron-like bird, flying with its extended neck and long decurved bill. He stood up with me to “verify” my identification before those in attendance. My age put me at a disadvantage, and our report was met with insulting comments, such as “Why didn’t you put salt on its tail, Sonny?” I left the meeting thoroughly humiliated, resolved that I would never again associate with this “old man’s club!”

Imagine my surprise to learn from Boyle’s narrative that the first Glossy Ibis nest in New Jersey was found in 1955, and that the species was, by 1978, “the most common colonial waterbird in the state.” Even more surprising is the fact that its population crashed during the next twenty years to only “350 to 400 birds, about 10% of the 1978 population.”

I never saw a Red-bellied Woodpecker during the 1940s and 1950s, though it expanded its range in the 1960s and 1970s, and now the species is common and widespread in New Jersey.

The Tufted Titmouse was just invading northern New Jersey when I saw my first one on May 15, 1949 in the Overpeck Creek area on a “Big Day” with Floyd Wolfarth and Louis Fink, two prominent local birders. I did not see my first local Northern Mockingbird until 1960, though they now may be found commonly in most parts of New Jersey.

The approximate line of demarcation separating the ranges of Black-capped and Carolina Chickadees still appears to be the Raritan River, just as it was when I was a child, but I now learn from Boyle that there is an “island” of the Black-capped species at Sandy Hook. This is useful information for any birder planning a visit.

White-crowned Sparrows were never very numerous, and they rarely spent the winter in my neighborhood. Now they are uncommon but regularly found during the winter.

These are but a few of the memories stimulated by my perusal of the contents of The Birds of New Jersey. It is an important and timely addition to the fund of knowledge about the rich avifauna of the Garden State. Resident birders will surely refer to it frequently. Any birder who is planning a visit to the state will find this to be a most useful resource.

Also available from Amazon,com

Kindle Edition $9.99

Hardcover $55.00

Paperback $16.47

Page images are from Amazon.com’s “Look inside The Birds of New Jersey: Status and Distribution“