Book Review- Birdwatcher

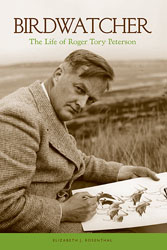

BIRDWATCHER

BIRDWATCHER The Life of Roger Tory Peterson

by Elizabeth J. Rosenthal

The Lyons Press, Guilford, Connecticut

Based upon interviews with hundreds of Roger Tory Peterson’s family, friends and associates, and supported by pertinent excerpts of his and others’ writings, Elizabeth J. Rosenthal chose an interesting approach to his biography. The result is a balanced and highly readable history of Roger’s central role in building the hobby, sport and science of birding into an essential part of the environmental movement.

Parallel narratives with various themes overlap deliberately, avoiding the problems with a chronological approach which may cause the reader to repeatedly refer back to earlier periods in the life of the subject, in an attempt to piece together people and events. While Peterson’s birth, on August 28, 1908 is recorded on the third page, and his death, in 1996, on penultimate page 389, this is not a serial recitation of events. Rather, in nineteen chapters, the author takes us through six selected aspects of his path to fame, revealing not only his great strengths and achievements, but also his weaknesses and failures.

A truant paperboy from Jamestown, NY, twelve year old Roger had an “epiphany,” when an apparently lifeless flicker burst into flight at his touch: “Ever since then, birds have seemed to me the most vivid expression of life.” Ernest Thompson Seton’s Little Savages book inspired the boy Roger to develop a system to identify ducks, and eventually other birds, by their “uniforms,” or distinctive plumage characteristics. As a young naturalist at the new Chewonki, Maine Audubon Camp, he introduced this concept to his students. It was to become famous as the “Peterson System” of bird recognition.

In 1936 he married Mildred Washington, who was a camper at Chewonki, but their relationship was strained and lasted only about five years. We follow his early career as educator and bird artist, and in 1937, as author of the groundbreaking A Field Guide to the Birds, through its second revision, in 1939. In 1942 and employed by the National Audubon Society, Peterson viewed the last Ivory-billed Woodpeckers in Louisiana’s Singer Tract.

He was drafted into the US Army and married Barbara Coulter, who was to become the most important figure in Roger’s life. Barbara learned her birds from the “old Chester Reed guide” that was always on the windowsill of her family’s breakfast room. In the Army, Roger conducted a flawed study of DDT which concluded that it is not harmful to birds. Eventually, he joined the science-based campaign to ban the pesticide. He supported Rachel Carson during her long and contentious war with the chemical companies and land grant universities who fought the DDT ban. There followed an extremely productive period of writing, most notably his authorship of Birds Over America, that showcased the beauty of birds as well as his prose. He authored or collaborated on the acclaimed series of Peterson Field Guides, and traveled the world as the most recognizable naturalist of his time.

In the meantime, as Roger expanded his horizons, Barbara Peterson evolved into his general manager. When he co-authored the immensely popular Field Guide to the Birds of Britain and Europe, a British ornithologist named James Fisher was editor. They developed a 20 year friendship, embarking in 1953 on the famous hundred day trip around North America from Newfoundland to Alaska via Mexico, to be chronicled in their book Wild America. James’s death at a young age devastated Roger.

Often overlooked by casual birders, Peterson’s contributions to the cause of bird and habitat conservation are extensively covered in this biography. Besides his work in North America on the decline of the Osprey, Peregrine Falcon and Bald Eagle due to DDT, he was an imposing force for species preservation at home and abroad. From his bully pulpit, he educated the public and lawmakers about endangered species and the causes of their decline, and effectively lobbied for funding of conservation programs. In Spain, he fought to spare the huge Coto Doñana from agricultural and commercial development. Although the struggle continues to this day, Peterson had a central role in obtaining public support and funds for the Coto’s preservation. Likewise for Lake Nakuro in Kenya, especially famous for its millions of flamingos, and Midway Atoll, where Peterson helped thwart a plan to exterminate its entire population of Laysan Albatrosses. And so on: Patagonia and Tierra del Fuego, Argentina, the Galapagos Islands, and the Antartic—in each case Roger was instrumental in changing the tide against development and exploitation.

We gain insights into Roger Tory Peterson’s personal traits— his enormous intellect and excellent memory, his shyness, detachment from family life, his absentmindedness and dependence on others to meet many of his personal needs. Yet, he was dissatisfied with his painting career, wishing to devote more time and effort into “painterly” works rather than “illustrations.” In his later years he appeared to be competitive with and jealous of the younger field guide authors, and was severely stung when the new crop of birders insensitively criticized and even ridiculed the fourth (1980) revision of his Field Guide.

After years of emotional estrangement, his marriage to Barbara ended amicably in a 1977 divorce, probably because Virginia Westervelt, who subsequently married him, supplied some of the nurturing and adulation which he craved. Virginia exercised great control over Roger’s schedule, deciding who could make appointments with him, and when, to the great distress of his family.

Roger was “shortsighted,” and some said he was obsessed and wanted to talk and think only about birds. Yet, this greatest weakness was also the source of his strength— an ability to focus on his subject. And the truth is that Peterson was an extremely well-rounded naturalist, having a great interest in the entire natural world: flowers and insects, and especially ecology. The book details the several times when he neglected his own health and safety in pursuit of birds, the most famous incident being his near-drowning and rescue by the Coast Guard off the coast of Maine.

Roger Tory Peterson’s most enduring legacy was the inspiration he provided to a whole new generation of birders. Rosenthal devotes an entire chapter to thumbnail sketches of Peterson’s “Worldwide Progeny,” who owe so much to their mentor. All are names familiar to serious birders. The book includes fourteen pages of photographs of Roger and his friends and associates through the years, and a list of all the people interviewed by Rosenthal. There are also extensive chapter notes and suggestions for further reading. A very useful feature is the fourteen page index that permits quick cross-reference to people and events.

So many times, as I read Elizabeth Rosenthal’s biography, my mind wandered back to my own experiences over the decades. I grew up with Roger Tory Peterson. He was my friend and constant companion. I first met him when we both were emerging from the depths of the Great Depression. He, a twenty-something naturalist and painter, and I, a six-year-old who, as a toddler, watched pigeons and starlings from the back window of an apartment over a meat market in New Jersey.

It was my mother who introduced me to Roger, unwittingly fanning a spark that was to grow into a flame. Only today, facing the irony of a recession and the specter of another Depression, do I realize what a sacrifice it was for my mother to spend $2.75 for the 1939 revision of the first edition of Peterson’s A Field Guide to the Birds. In today’s economy, that comes to $34.37, plus tax. The book supercharged my interest in birding and opened the door to a lifelong hobby– it might be called an obsession.

The Guide replaced my first “real” bird book, a pocket-sized copy of Land Birds, by Chester A. Reed. It was badly defaced, for I traced the outlines of the book’s small format bird pictures, perhaps to engrave them into memory. As soon as I matched one of them up with a dooryard sparrow, robin or jay, I penciled “SAW” in big block letters over the corresponding image. Alas, my initial Life List was eventually assigned to the trash heap. Not so with my treasured original Peterson Guide. Although now yellowed, soiled and loosely held together, it is witness to the respect I accorded it.

Many more times, and in many places, I consulted Roger and delighted in what he told me about birds, in the pages of the Junior Book of Birds, the Junior Audubon leaflets, and in his Birds Eye View and other columns in Audubon and Bird Watchers Digest. Only twice did he speak to me in person, but both times I was part of a large audience. Once, when I was in my teens, I attended an Audubon Screen Tours presentation which he personally narrated. I cannot remember the topic of his film, nor a single word he said. It must have been in a state of awe at finally seeing the Great Man. Later my son and I flew out from Dallas to New Mexico, where Peterson spoke to a packed house during the Festival of the Cranes. We never got near him, and he birded Bosque del Apache privately with a small group.

Ever faithful, I purchased every subsequent revision of the Eastern and Western as well as the Texas bird guides, as well as many of the Peterson Guide series. In his magazine columns, I followed his adventures and his brushes with death. I especially remember one column in which he complained that, with advancing age, he had developed very poor tolerance to heat. He felt he would be making far fewer trips to Arizona. Rosenthal’s biography relates the beginning of Rogers descent into terminal ill health. In September, 1995, eighty-seven year old Roger spoke at a dedication ceremony in McAllen, Texas, in 91 degree heat. After giving brief remarks in the full sun, he collapsed with heat exhaustion. A stroke followed not long after, and he died in July 28, 1996.

Like Roger, I had a “epiphany” as a kid, when, concealed by shrubbery, I peered into a clearing where a courting Rose-breasted Grosbeak was displaying before a female of its kind. The color and the beauty of its dance have stayed with me. My wife, Mary Lou had a similar experience that started her into birding. Before we took our first birding tour together into Arizona (to which she reluctantly consented), she thought it best to at least look in my Field Guide at the birds that were supposed to be such an attraction. She settled on the Elegant Trogon, as if she could just order one up for the trip! Well, in Garden Canyon, she saw a male and a female trogon, both at close range and in beautiful plumage. That did it.